When Pre-Flight Prep Becomes Criminal

The accident took place on the 9th of September 2017 shortly after take-off from Manchester City Airport, a municipal airfield near the Manchester Ship Canal in the north of England. Manchester City Airport opened in 1930 and has not changed much since then: the control tower, terminal building and hangar are all the original buildings (now listed). There are four grass runways but the airfield is often closed because they become waterlogged; the airfield is on the edge of Chat Moss, a large area of peat bog. Additional drainage was added in 2011 as the original clay pipes had deteriorated but the low-lying land is still vulnerable to becoming waterlogged.

There had been a significant amount of rain that morning and standing water was forming at the airfield. A NOTAM (notice to airmen) warned that further heavy rain might lead to the airport closing at short notice and the automatic terminal information service advised pilots to avoid the centreline and southern sections of the active runway, 26R.

The departure path from runway 26R crosses the M62 motorway about 600 metres beyond the end of the runway. After the motorway is an overhead power line, about 1,400 metres beyond the end of the runway.

The accident aircraft was a Piper PA-28-140 Cherokee, registration G-BAKH. The pilot received his Private Pilot’s Licence in 1986 and he had 15,000 hours with 10,000 hours on type. The flight was listed as a general aviation pleasure flight to the Scottish island airfield of Oban. The flight consisted of the pilot and three passengers: bird watchers who were promised a flight to the nearby island of Barra, where an American Redstart bird had been spotted for the first time in 30 years in the Outer Hebrides.

The pilot fully refuelled the aircraft and then waited while a runway inspection was carried out. After hearing that the runway was very wet, he requested permission to conduct an “accelerate and stop run”, in order to verify that they’d be able to take off within the runway available.

This was sensible: a grass runway requires a longer take-off run and if the grass is wet, then the take-off run is longer again. The Skyway Code states that on a wet grass runway, you should increase the distance needed by a factor of 1.3 to take off.

Tower cleared the pilot to do a test run and he entered the runway and accelerated before braking, as planned, and backtracking along the runway, ready to do it for real this time.

Once cleared for departure, the pilot set two stages of flap for a short field take-off, hoping to reduce the amount of runway needed to get off the ground. During the take-off roll, he kept the aircraft to the right of the runway to avoid the worst of the wet grass. Somewhere between halfway and three-quarters of the way down runway 26R, he began applying back pressure to the yoke to rotate.

A witness described the Piper Cherokee as crawling into the air, nose high. It made it some twenty feet into the air before running out of energy; the pilot complained that the aircraft was completely unresponsive, failing to climb or accelerate.

They were heading directly towards the power line so the pilot began a left turn before the motorway in order to avoid it. I’m not sure he had much choice now that he was in that position but the effect of the turn was a further reduction in energy and the aircraft was no longer capable of flying.

The birdwatchers in the aircraft later spoke to the Daily Mail. The passenger in the front right seat described the take-off:

The pilot pulled the throttle and off we went. He didn’t say what to do in an emergency or in a crash, no life jackets or procedures were given. Visibility was very poor, it was raining heavily and it was a small tiny windscreen.

We were in the air and all of a sudden the plan banked to the left, it tilted, I looked below and I could see the motorway. A few more seconds went in and then I heard the comment: ‘not enough power’. It wasn’t very reassuring.

The impressions from the backseat were slightly different, as they did not have the view of motorway stealing their attention. One of the two men in the backseat said:

When the plane was in the air, it wasn’t too long before it sounded like when a car goes up a hill on a low gear and it’s making a lot of noise, there seemed to be a loss of power on the aircraft – but there was no discussion or talking about it.

‘We just seemed to lose power and I remember seeing pylons in the distance and I thought if we didn’t get any more power we’re not going to make this. The plane banked sharply and we hit the top of the trees going over the motorway then we landed with a sudden jolt. There was a really strong smell of fuel and a lot of blood from Alan’s injuries.

The pilot aimed for the only landing area available, a dark field directly in front of him. Unfortunately, the field was planted with potatoes and, upon touching the ground, the landing gear sank deep into the soil, causing the aircraft to come to an abrupt stop. The pilot and front seat passenger both hit their heads on the instrument panel (hence the blood) and the rear seat passengers also suffered minor injuries.

All four swiftly evacuated the aircraft as the wing had partially broken off and the fuel tank had ruptured. Luckily there was no fire. Emergency services made it to the scene in less than ten minutes.

No significant faults were found with the engine, which had been rotating on impact, but there was some wear of the camshaft which was typical for such an engine. This damage could account for a 5-8% reduction in available power. This was clearly not the cause of the lack of power in the initial climb.

However, the report of the aircraft “crawling” into the air with a nose-high attitude gives us a pretty good hint as to what might have been the cause. The investigators quickly focused on the weight and balance of the aircraft.

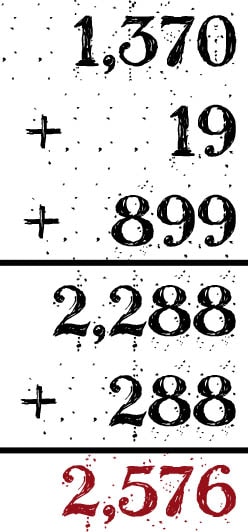

Time for some quick maths. The maximum take-off weight (MTOW) for the pilot’s Piper Cherokee was 2,150 pounds (975 kilos). The aircraft had a basic weight of 1,370 pounds (621 kilos). Items in the aircraft weighed 19 lbs (9kg). The pilot, the three passengers and their baggage weighed a total of 899 pounds (408kg).

I should mention that the passengers, pilot and baggage were weighed after the crash. The pilot admitted that he had not weighed them before the flight, quipping that he worked on the principle that if they fitted through the door then they could fly. Later he said his big mistake was that he forgot to include his own weight into the equation.

Thus, the Cherokee with the passengers and baggage on board weighed 2,288 pounds (1,038 kilos), already over the maximum take-off weight of 2,150 pounds (975 kilos). The pilot didn’t realise or didn’t care. In any event, he was happy that they were ready to go and fuelled the Cherokee to full capacity, adding another 288 pounds (131 kilos).

At 2,576 pounds, with an MTOW of 2,150 pounds, the aircraft was now clearly overweight and would continue to be so even when it was out of fuel, so taking fuel burn into account doesn’t really help.

The Piper Cherokee at maximum weight requires a take-off distance of 2,090 feet. The grass was wet, which means that distance needs to be increased by a factor of 1.3 which gives us a take-off distance of 2,717 feet. Taking into account the fact that the Cherokee was beyond the maximum take-off weight but still in balance, and allowing that some fuel would have been burned in the taxi and the test run, the take off distance required was calculated to be approximately 3,912 feet (1,192 metres).

The pilot did ask to check the take-off run required that day before his departure. However according to one witness, when the pilot then attempted the “accelerate-stop run” to check the take-off run, the aircraft showed no sign of being able to lift off.

That’s no surprise. They didn’t have 3,912 feet in which to accelerate. Runway 26R at Manchester City Airport has a total take-off distance available of 2,103 feet (641 metres).

The distance that the overweight Cherokee needed to lift off safely was nearly double the length of the runway.

Note that none of this is taking into account the condition of the engine, which was running fine but probably was delivering 5-8% less power than expected.

The pilot clearly never considered his weight and balance for the flight. His test run did not prove that he had enough runway for acceleration. He decided to continue with the flight with two stages of flap, which he described as setting up the aircraft for a short field departure.

Now, this take-off technique was not based on anything in the Airplane Flight Manual (AFM) but the pilot is correct that would have helped to reduce the take off run required by increasing the lift. However, with the nose high and two stages of flap, it did nothing to increase the aircraft’s ability to fly. Between the drag from the flaps and the slow rotation speed, it’s actually pretty amazing the aircraft managed to crawl into the air.

Having managed that, the pilot might have kept the Cherokee flying if he’d dropped the nose long enough to increase his airspeed to allow him to climb. But this is counter-intuitive at such a low level and besides, they were rapidly approaching the power line. Flying twenty feet above the motorway and under the powerline might look good in an action film but it isn’t a viable plan. To the pilot’s credit, he turned instead and did the only thing he could: pick a field and attempt to land.

Somewhere in all this, a further fact came clear. The pilot, who did not hold a Commercial Pilot’s Licence, had offered to fly the birdwatchers for a fare of £500 per person for the flight to the Scottish island. They had no idea that he was not entitled to charge for the flights. These days, regulations are a lot more lax when it comes to pilots asking for help paying the fuel of a flight but this was clearly not a cost-sharing exercise: the passengers believed they were purchasing a commercial service and the pilot was making about £1,000 in profit.

Before the final report was released, the pilot was arrested. He reacted furiously, telling the police that his actions that day had saved four lives; he should receive a commendation! He then joked that Warner Brothers had already contacted him to make a film of the event, which would be titled Miracle on the Ship Canal.

One does not receive the impression that the police were impressed by his wit.

Once in court, he told the jury that he was a hero, that the crash was a deliberate act to save the lives of his passengers and that the only error he made, which he admitted was grave, was not to include his own weight in his calculations.

Based on photographs, the pilot is not a small man and yet it seems hard to believe that he felt that this was his only error. He was charged on seven counts most of which related to the reckless endangerment of the aircraft, the passengers and the people on the ground and that he was charging his passengers with the intention of making a profit.

The pilot was the first in the UK to go to Crown Court trial for either reckless endangerment of an aircraft or of illegal public transport. The prosecuting lawyer received his PPL when he was 17 and says he still flies regularly, which meant he had the expertise and experience to make it clear to the jury what could reasonably expected from a pilot under these conditions.

In February 2019, the Crown Prosecution Service announced that the case was completed

Robert Murgatroyd’s reckless actions could have had fatal consequences that day. Out of pure greed he put his passengers, road users and anyone else in the immediate area’s lives at risk.

Throughout the case he denied he was responsible in any way for the plane crash or that he had flown it for profit. In police interviews he described himself as a hero for the way he handled the forced landing and said that there should be a Hollywood film made about him.

However the CPS presented to the jury the overwhelming evidence against him proving he charged his passengers £500 each, filled the fuel tanks to the brim, made no checks on the weight of the full plane and had the wrong flight manual on board.

Robert Murgatroyd (DOB: 19 May 1966) was convicted of the following charges:

- Endangering the safety of an aircraft

- Endangering the safety of a person

- Illegal public Transport

- Flying otherwise than in accordance with a licence

- Flying otherwise than in accordance with any conditions/limitations contained in the aircraft flight manual

- Failure to comply with the insurance regulation

- Flying without the aircraft flight manual

He was sentenced with three and a half years in prison and then, on the back of the police investigation, charged and found guilty of insurance fraud which led to a further 22 weeks, to be served concurrently.

All of the passengers have recovered fully but the Cherokee was written off.

A special thank you to Ian Howat for allowing me to use his photograph of the accident aircraft.

This, I think, is a rather lenient sentence. Did he at least lose his licence?

I certainly hope so! I didn’t think to check but I’m sure he must have.

Knowing Sylvia’s diligence we can accept the story and the facts at face value.

But quite a few things do not seem to add up:

The pilot obtained a PPL in 1986 and in 2017 had clocked up 15000 flying hours, that means on average 500 hours per annum.

I got my PPL in 1967, my CPL in 1969 and my ATPL some years later.

I flew commercially until 2008. I logged 22000 hours in that time, which included flying professionally as well as recreationally. I was an active member of the Tiger Club in Redhill. I averaged about 550 hour per year. So the inevitable conclusion must be that this PPL must have flown for hire and reward all the time, which is probably CRIMINAL in itself.

His “testing” acceleration on the runway is NOT a hallmark of professionalism. All information that he would have needed would have been in the aircraft flight manual, which he neither consulted nor had on board; btw, I never knew that a PPL is required to carry this document on a light single-engine aircraft. Is this something new?

So:

The pilot had been breaking the law for many, many years.

He was making a lot of money with his illegal operation.

He attempted a take-off on a short, unpaved runway on wet grass.

The aircraft was seriously overloaded.

He used a “short-field” take-off technique that was not approved.

As a result: the aircraft got airborne on or even below the stall speed, on the “wrong side of the power-drag curve” with so much drag that the engine power was insufficient to enable the aircraft to accelerate and get out of this situation.

Besides: the stall speed INCREASES with weight, so it may be assumed that this pilot set himself up for an unavoidable accident.

And the incredible ARROGANCE to make the claim that he was a “hero”. A VILLAIN would be a better description.

This character has no business to be in charge of any aircraft and yes, I do hope that his licence will have been not suspended but REVOKED, permanently !

And who invented this nonsense of “concurrent sentencing”? A concurrent sentence is in fact no sentence and Murgatroyd’s misdemeanours were in the category of “Very Serious”, in fact outright CRIMINAL. I agree with hat_eater that the sentence seems absurdly lenient, also in light of his attitude after the crash.

It is possible that Murgatroyd had a CPL and had it revoked. His company offered flight training, plane rides, and hired out their panes as well. The URL is visible on the plane picture in the article.

I dropped some of the history as the piece was already too long, but the pilot had previously worked as a flight instructor, which is where I would think he’d built up the hours. In addition, as Mendel says, he operated multiple aircraft as Fly Blackpool. Three of the aircraft operated by him were involved in fatal crashes which is why the insurance issues arose; he did not give the details of the operation or that he’d been declined for insurance previously.

For the test run, I think that’s my GA background coming through here. I know it is all in the aircraft manual but with the Saratoga especially, I often found that what the AFM said the plane could do and what *I* could do were not always one and the same!

That said, I’ve never actually tried a test run, I just thought it sounded like a good way to get a quick feel for how the aircraft was handling. Knowing that it was overweight, of course, I wouldn’t expect that to save me!

(I’ve only flown overweight once, departing from Glenforsa on the Isle of Mull, and that was because someone had snuck a crate of whiskey into the back without telling me!)

I know this guy personally. For a number of years he operated as a flying instructor and held an ATPL and was the owner of an airline operating out of Blackpool, So the hours may be correct and despite losing his ATPL probably felt justified to charge for hire. I am not defending his actions. Just correcting some assumptions you made. He also owned three other aircraft crashed that resulted in fatalities. His sentence for insurance fraud was reported elsewhere as running consecutively.

When I read this, the 15,000 hours logged caught my attention. My first thought being that this had to be someone quite wealthy, or that it was P 51 time (referring to the Parker P51 pen as being the source of the hours). Why not get a commercial ticket? A pilot with a fraction of this experience should be able to pass a commercial check ride with ease.

My second thought, as I read through, was that a Cherokee 140 was a bit small for four adults. Had it been smaller than average people, there would be barely any capacity for fuel and with standard weights for males (which I believe do not apply to aircraft under 5 seats) the plane would have been at MTOW with zero fuel.

The pilot is lucky to be alive, plain and simple. Likewise his passengers. People have died in far less extreme overloads. There was a lot wrong with this flight and the PIC is responsible. I hate to wish imprisonment on anyone, but considering his conduct in this matter, I think he got off easy.

I’m glad that I live in a free society, but some people abuse their freedoms and having read to the end of the piece, that’s what seems to be the case. It’s not unique. When I was applying for my first job as an aircraft tech, one potential employer, a cargo operator, wanted to know if I was multi-engine rated so I could ferry planes to the west coast. I had the distinct impression that I would be ferrying planes that were loaded to the gills with freight and that I’d be doing a lot of ferrying. Less than a year later, that company lost their operating certificate after having two crashes in as many days. I’m really glad I didn’t get mixed up with them.

So this would seem a case of an operator flaunting the law and, apparently, getting away with it for years.

Rudy commented also on the 15,000 hours — as above, he worked as a flight instructor and operated multiple aircraft as Fly Blackpool. That doesn’t explain why he hadn’t done his CPL, as you say, it should have been trivial.

Looking at local flying forums, he seems to have quite a reputation in the Manchester/Blackpool aviation community! I didn’t like to repeat negative gossip though and most of it was quite hazy in any event.

“A pilot with a fraction of this experience should be able to pass a commercial check ride with ease.” When I was thinking about a commercial ticket, I found that the license in the US required an assortment of semi-aerobatic maneuvers that might demonstrate one’s precise control of the airplane but weren’t necessarily easy to learn and certainly weren’t usable in normal flying. I don’t know what the UK requirements are/were, but it’s quite possible that Murgatroyd (what an appropriate name!) would have had to spend practice time he didn’t have and fuel money he didn’t want to lose in order to qualify.

OTOH, I wonder how he managed to be a flight instructor (per one of Sylvia’s additions) without a CPL — is that a variation in the UK? In the US he wouldn’t be able to get an instructor’s certificate without a CPL (instruction being an example of flying-for-money); without a certificate, he could have taught covertly but wouldn’t have been able to sign people off to be tested for licenses. So it’s possible (as Mendel) notes that he had a CPL and lost it.

I think Sylvia could easily write a followup article on what comes to light when you google “Robert Murgatroyd Fly Blackpool”. He was apparently the owner and managing director of that company, which offers training and planes for hire and for charter. The “insurance fraud” Sylvia mentions refers to several previous fatal accidents involving his planes that he failed to tell the insurer about.

“In May 2013, an aircraft operated and insured by Murgatroyd was hired out to a pilot and it crashed at Caernarfon in Wales, killing one and seriously injuring 2 others.

Following that incident, in June 2014 Murgatroyd was convicted of flying an aircraft without a valid certificate of airworthiness, and was fined £300.

In October 2011, another aircraft operated and insured by Murgatroyd was hired to a pilot, and it crashed in Switzerland killing both occupants.

In February 2007, another aircraft operated by Murgatroyd crashed into the sea at Blackpool, killing the two occupants.

The police’s investigation found that in the hours before taking out the insurance policy with Sydney Charles Aviation Insurance, Murgatroyd had been declined insurance from another firm.”

Murgatroyd probably thought himself a hero because this time, nobody died.

I don’t normally include names of pilots but in this case, it was part of the sentencing document so I’d have had to redact it for very little value — and I did think that someone might search and find the previous crashes which I hadn’t managed to fit in! :D

It really was the Daily Mail Online’s Ryan Fahey who found them, I just found their article (but forgot the attribution).

Mendel highlights an interesting side of this story. Interesting, but also sad because it would appear neither Murgatroyd nor the authorities seemed to have taken his continued illegal activities seriously enough.

I mentioned that “some things did not seen to add up” in the context of his very high number of logged flying hours.

He – his firm – have been involved in a string of incidents, some with fatal consequences. Apart from those sad accidents that may, just may have been unfortunate but coinicdental, there have been questions about the way this operation was run: maintenance, insurance, even operating commercially without being properly licenced..

Yet Murgatroyd was let off the hook with a very light sentence.

I agree with Mendel’s sarcastic comment: “Murgatroyd probably thought himself a hero because, this time, nobody died.”

But was the sentence sufficient deterrence to stop him doing the same again?

As a P.S:

Many operators involved in different aspects of aviation, like flight training, rentals, even commercial operations, have an URL or other identifier on their aircraft. It does not necessarily mean that the aircraft is actually engaged in illegal activities.

I have flown the Cherokee 140 in my early days. The cabin size was not a problem when carrying even four adults, it was the engine power.

The aircraft was 5N-AEK. It was in Nigeria, so pretty hot. Yet, as long as the pilot would be aware of the performance restrictions and weight-and-balance there was no real problem.

I only had a problem once: these early Cherokees did not have toe brakes, but a hydraulic brake operated by a handle in the centre under the panel with a fluid reservoir mounted at an angle (I forgot the importance of the angle) under the engine cowling.

Once, landing at Kiri Kiri which was a relatively short grass strip, it ran out of fluid. Fortunately the grass was high where it ended at the fence of Kiri Kiri prison, or I would have risked going through the wire ending in the prison myself.

The Cherokee 140 was notorious when I started flying (1973) for having a back seat despite not being able to lift four people under average conditions; that’s why Piper created the Warrior, which was a 140 with assorted upgrades to make it a legitimately 4-person airplane. (The review in FLYING mentioned a tapered wing, with a sneer at the “Hershey Bar” wing of the 140.) This induhvidual had 10,000 hours in type; I wonder whether he ever read the manual and how often before he’d gotten away with flying an overloaded airplane.

Well Chip, I did carry four people from Lagos to Ibadan.

A husband, wife and their teenage daughter.

OK, none were very heavy and there was little or no luggage.

The aircraft did not need full tanks, it was just about one hour’s flying. I probably had the tanks only just over half full, enough for, let’s say two hours.

But still, in the tropics it would have been hot (and humid), a high “density altitude” even at sea level.

But I do not recall any performance problems, but then: I departed from airports with long, paved runways, not from a short, wet grass strip.

At last I have the knowledge to make a comment on one of Sylvia’s excellent articles! Oban isn’t an island, it’s a town on the west coast of Scotland.

Ouch! I see what I’ve done now, thank you for highlighting it.

Mentioning Sylvia: She admitted to having flown overweight once.

Something similar happened to me: I was bringing a few fishermen for a crew exchange; their trawler was somewhere I believe in Denmark.

My calculations showed that I was going to be a bit overweight, but not by very much. I should have weighed the baggage but I thought that I could get away with an estimate. It was a cold day and a stiff breeze down the runway. And the aerodrome, Lelystad (EHLE) was below sea level. But the take-off run was very much longer than I had been expecting.

It was only later that I discovered that the fishermen had brought a few loaves of bread. They did not look very heavy but they WERE !

They had been deep-frozen and apparently that had multiplied the weight by probably a factor of 3, maybe even 4. I never knew that.

But although the runway was grass, at least there were no obstacles.

Lelystad, in those days, had not been open long and the town was newly built. Still virgin territory in the most literal sense.

And so I learned in my early days as a commercial pilot the importance of determining the accurate take-off weight of an aircraft.

I did have quite a few hours in my logbook then, but mainly on Super Cubs other single-engined aircraft. I would have been found guilty if anything had happened. I had maybe some excuses, one being inexperience. Which certainly did not apply to Murgatroyd, although he was treated far more leniently than I could have expected if things had gone wrong.