Near Miss at Midway

This year is turning out to be quite the collection of aviation incidents, with the dramatic video of Southwest flight 2504’s go-around at Chicago Midway making headlines around the world. This is feeding into a growing narrative of aviation issues, especially in the US, with many expressing concern that aviation is no longer safe.

Part of this effect is the selective attention of the media. When Malaysia Airlines flight 370 disappeared, news sources were suddenly full of incidents and accidents in south-east Asia, even though there was no uptick in accidents in the area. Simply put, they had not reported on similar and much more serious accidents in previous years, however in the aftermath of MH370, their attention was drawn to the regions. One of the reasons I started my Why Planes Crash series was to highlight accidents in a given year that may not have received media attention, contrasting the big-name incidents with lesser-known ones in a wide range of places. I’m working on that series again and it’s interesting to consider what might or might not make the cut once we have a better handle on aviation in 2025.

It’s difficult to make strong statements at this stage, just two months into the year. However, as of right now, the statistics look similar to previous years, excepting 2020 which had far fewer flights. On Axios, Alex Fitzpatrick considers the data from 2021 to 2025 (as of the 21st of February) and concludes that 2025 is on pace for fewer fatal aviation accidents compared to 2021-2024. The fatal collision of American Airlines flight 5342 with a Sikorsky H-60 “Black Hawk” military helicopter is the big outlier here, as the first major fatal commercial air disaster in the US since Colgan Air in 2009. This will obviously affect the statistics but does not actually demonstrate that aviation is less safe in 2025 than it was in 2024, any more than MH370 showed us that aircraft were more likely to vanish with no explanation.

The near-miss at Chicago Midway, caused by a runway incursion, is not so very rare. The FAA lists an average of 1,700 runway incursions per year from 2021-2024, the great majority of which had no immediate safety consequences or plenty of time and/or distance to avoid a collision (scroll down for runway incursion data). An aircraft inbound to land is watching the runway very carefully to make sure that the runway is clear for landing. I strongly suspect that the flight crew of Southwest flight 2504 were watching the business jet before it even entered the runway and that the conversation in the cockpit went something like “What’s that jet doing? It’s not going to try to cross, is it? Is it? Dammit, it is. Full power, go around.”

That said, Elon Musk is not exactly inspiring me with confidence.

What makes this incident particularly newsworthy is the quality of the video as it steadily zooms into the landing aircraft just in time to see the business jet enter the runway before the Boeing 737-800 pulls away.

Watch the full-sized video on StreamTimeLive channel on YouTube.

So: what happened?

Southwest Airlines flight 2504 was performing a scheduled domestic passenger flight from Omaha, Nebraska to Chicago Midway, Illinois. The aircraft was a Boeing 737-800, registered in the US as N8517F.

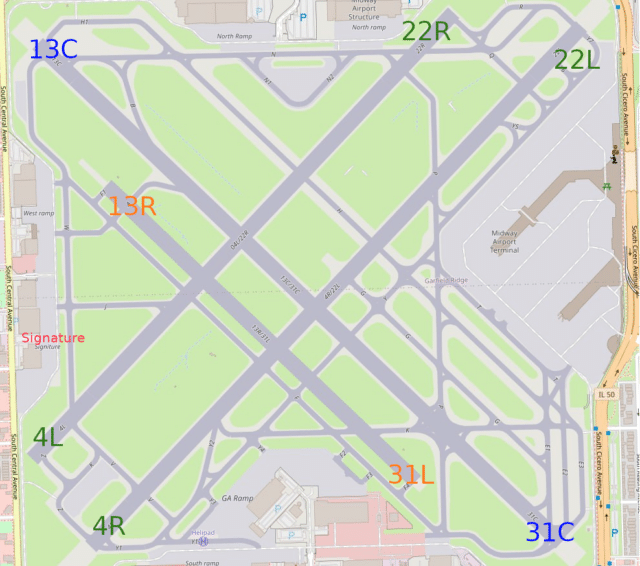

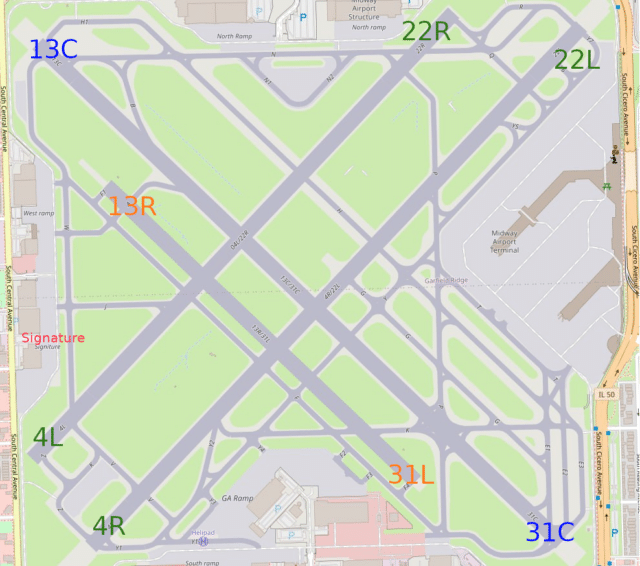

Chicago Midway is a large and very busy airport with multiple runways:

4L/22R and 4R/22L are parallel runways running north/south (ish). 13C/31C and 13R/31L run east/west (ish).

Of relevance here is that 13C/31C is the longest runway at 6,059 feet (1,847 metres) and is ILS equipped, designed for commercial flights, while 13R/31L is a short runway used for light aircraft.

Southwest Airlines flight 2504 was coming in to land at Chicago on runway 31C after the one-hour flight from Omaha.

The business jet was a Bombardier Challenger 350, registered in the US as N560FX, owned and operated by Flexjet in Cleveland, Ohio. The business jet primarily flies short domestic hops in the US. Flexjet offers private flight services using business jets ranging from the Gulfstream G650 to Phenom 300. They pitch the Challenger 350 as a super-midsize executive jet which accommodates up to nine passengers in a double-club configuration, with the ninth seat described as the “seamless belted lav option”. The Bombardier Challenger 350 requires two pilots as flight crew.

That morning, the Bombardier Challenger 350 was performing a flight from Chicago Midway to Knoxville, Tennessee. They contacted the ground controller as Flexjet 560. You can follow along with the ground audio here.

Flexjet 560: Flexjet 560, Signature with Tango

This is the aircraft introducing itself and its position (on the Signature ramp) with information Tango.

Midway Ground: Flexjet 560, runway… actually, departure frequency is 119.35. Runway 22 left. What taxiway are you coming out of?

Flexjet 560: We’re over at Whiskey.

Midway Ground: Roger, taxi via Foxtrot and hold short of runway 22 right. Plan for runway 22 left.

Flexjet 560: All right. Planning for 22 left. Foxtrot, Whiskey.

I’m not going to pretend I know the layout at Chicago but as they announced they started on taxiway Whiskey, it doesn’t make sense to proceed to Foxtrox and then go back to Whiskey. More importantly, they haven’t confirmed that they understand to hold short of runway 22 right. Hold short is an instruction to not enter the runway. So in this instance, the jet is planning to depart from runway 22 left but to get there, they need to cross runway 22 right. The readback should include the fact that they know they are to continue to 22 right but not cross it until given permission.

The controller didn’t seem to notice that the readback was incomplete. Presumably, there was a brief discussion and look at the charts in the cockpit as the flight crew called back.

Flexjet 560: (possibly a different voice?) Ground, we just want to confirm our taxi instructions for 22 left from Signature.

Midway Ground Where on the ramp are you, sir?

Flexjet 560: We’re at Signature Aviation, at Alpha uh… Alpha taxi.

I’ve marked Signature on the map above, for reference.

Midway Ground: OK, Taxi Alpha, Foxtrot, hold short of 22 right.

Hold short is an instruction to not enter the runway. So in this instance, the aircraft is likely to depart from runway 22 left, which is way on the other side of the airport. To get there, they are going to need to stop at 22R and wait for the instruction to cross.

Flexjet 560: Alpha, Foxtrot, hold short of 22 right.

Midway Ground: Flexjet 560: turn left on runway four left, cross runway 31 left and hold short of runway 31 Centre.

So, these are new instructions. The aircraft is to turn left onto runway 4L (presumably not in use). I’m repeating the map here so you can see the route along the runway, crossing both the short light aircraft runway (31L) and the long commercial traffic runway (31C).

Flexjet 560 is given permission to cross runway 31 left, which means they know there are currently no light aircraft inbound. The sequence for crossing a runway is much like crossing a road: look left and right, calling out that the direction is clear for both left and right before entering the runway. The point is that mistakes happen and one should not only be told that it is safe to the cross the runway but to look and verify that it is clear.

The final statement in that instruction is to hold and wait before crossing 31C (the active runway).

Flexjet 560: All right: left on four left, cross 22–er 13 Centre

This is the call that has been getting a lot of the attention, as it is pretty confused. He’s saying to cross 22, which is incorrect, as the new route is on 22R (heading the opposite way). There was no mention of 13C at all. The pilot was probably thinking of 13R, but the controller is using the direction that is in use, which is at that point 31L. It isn’t hard to see how a pilot could get confused here, I know, but it is important to understand the chart and the airport. And it’s critical to respond with a clear readback to show the controller that you understand what you are to do.

The controller correctly jumps on it.

Midway Ground: Flexjet 560, negative. Cross runway 31L, hold short of runway 31C.

Flexjet 560: Cross 31 left, we’ll hold short of 31 Centre.

What we all know now is that Flexjet 560 did not hold short of runway 31C. That’s the runway where Southwest flight 2504 was coming in to land. Let’s switch to tower frequency:

Midway Tower: Southwest twenty–

This is the Tower controller seeing the Flexjet aircraft entering the active runway and calling Southwest urgently. Looking at the video, you can see that the Boeing 737-800 was already in the flare ready for touchdown, just a few feet above the runway.

Southwest 2504: Southwest 2504 is going around.

But the controller doesn’t get to finish the call because the Southwest crew are already going around. (Yay!)

Midway Tower: Southwest 2504, climb and maintain 3,000 feet.

Southwest 2504: 3,000 feet.

Back on the ground frequency, things are a little strained:

Midway Ground: Flexjet 560, hold your position there.

Flexjet 560: Holding position.

So what went wrong? The Flexjet pilot had questions about the taxiways, so the most likely explanation that I can think of is that the flight crew thought they were crossing 31 left, which they had permission to cross, and didn’t realise that they were entering the active runway. This does not explain why they did not see the inbound Southwest flight before entering the runway..

Midway Ground: Flexjet 560: continue across and hold short, hold short of Hotel.

Flexjet 560: Cross and hold short of Hotel.

Midway Ground: Flexjet 560: your instructions were to hold short of runway 31 Center.

Meanwhile, on the Tower frequency:

Southwest 2504: Tower, [this is] Southwest 2504. How did that happen?

Midway Tower: Southwest 2504: climb 3,000 feet, contact Chicago Approach 128.2

Translation: We don’t know either, buddy.

The Boeing 737-800 climbed out to safety before approaching the runway again, landing safely on runway 31C about 15 minutes later.

Ground are pretty specific though:

Midway Ground: Flexjet 560, Possible Pilot Deviation, advise you contact Midway Tower at a number when you’re ready to copy.

Translation: Stop the plane, take this phone number, and phone the Tower and explain yourself.

This phone call means you have screwed up badly and air traffic control want a word with you. Possible Pilot Deviation requires an inquiry. This happened to me only once, when I was slow to clear the runway at Alderney and wasn’t sure where to turn next, because I hadn’t familiarised myself with the airport layout before arriving. I survived.

This pilot will probably not: that incident will get escalated to the FAA and I can’t really imagine a scenario where they will not take enforcement action, suspending or terminating the pilot’s license.

Flightaware have created a great video for us, which combines the ADS-B data, following the track of the aircraft taxying on the ground, and the ATC audio from both Tower and Ground frequencies.

Flexjet released an immediate statement which was printed by USA Today:

We are aware of the occurrence today in Chicago. Flexjet adheres to the highest safety standards and we are conducting a thorough investigation. Any action to rectify and ensure the highest safety standards will be taken.

This morning’s comments from the National Transportation Safety Board

assigning blame are premature. We do not comment or speculate about any aspect of a safety investigation, especially in these very early stages, just as we expect all other professional organizations and agencies will do. A genuine safety culture is one of continued learning to raise standards, and that is precisely what we are undertaking.

Meanwhile, NTSB Chair Jennifer Homnedy gave a rather simpler version of events. “Flexjet 560 was told to line up and wait and hold short of runway 31C, which Southwest was landing on, and they failed to do so.”

I’m missing a point in the first part of your analysis. The bizjet wasn’t directed to go back to Whiskey AFAICT; he was told to go from Whiskey to Foxtrot as if that would take him to the border of 22R, but echoed back Whiskey after Foxtrot. That’s unclear at the least, and suggests at the worst that the pilot communicating was already either overloaded or careless.

I know an unfamiliar airport can be difficult to navigate; I wound up on a runway I wasn’t supposed to be on at Northeast Philadelphia many years ago. But that was at night, on my only time at that airport, after some of the heaviest flying I ever had to do (scudrunning into New Haven, then my first unsupervised instrument flight — with a passenger). Unless the Flexjet pilots had overbooked, they should have been in good shape to fly, they shouldn’t have been unfamiliar with the airport, and they weren’t flying at night; I’m wondering if they were just being careless (possibly due to hurry), and if so whether they’d been careless before without being caught at it (cf the discussion of the Bedford (Hanscom) crash from several years ago).

A question now that I’ve stared at the tiny letters on the graphic: is there a standard for referring to a runway that a pilot is going to approach from the middle rather than an end? I expect they would have seen a sign “4L/22R” at the end of Foxtrot (looks like the short east-west taxiway from 4L/22R to the middle of the ramp at the left side of the graphic), but the controller calling it 22R and then 4L may not have been as clear as possible.

OTOH, the statement from Flexjet management is beyond unhelpful; I hope they get smacked down hard. My partner thinks their legal department told them to say that; I would have thought a smart lawyer would tell them the first rule of holes.

I suspect this is part of the holes lining up, along with which controller should be talking to pilots crossing an active runway. I agree with you that the pilots had the responsibility of knowing the airport layout and taxiways but at the same time, that alone shouldn’t be enough to risk an accident. I think this analysis will end up highlighting a lot of potential for improvement.

Right, my impression of this call is that the pilot was already confused, which fits in with the pause before asking for directions again.

Your recent guest post, https://fearoflanding.com/accidents/a-concorde-close-call-not/ , is another good example that most go-arounds are not near misses. They’re often due to ATC at busy airports sequencing take-offs and landings on an “if all goes well” basis to maximise throughput (which reduces passenger wait times), and then taking aircraft out of the sequence to queue them “at the back” when a crew needed more time. Since both ATC and the crew of the approaching aircraft are aware of that potential conflict, the resulting go-around typically causes no issues.

That said, sometimes they do.

In an incident involving a Mesa CRJ-900 and Skywest ERJ-175 at Burbank on Feb 22nd, 2023, the local controller was distracted by another aircraft, and the Mesa crew initiated a go-around on their own, but broke minimum separation as they did so, with TCAS helping to prevent a mid-air collision.

And a TUI B787-8 at Birmingham, on Dec 21st 2023, had to go around (due to windshear), and because ATC queued them “at the back” (and other reasons), landed on minimum fuel, which counts as an emergency (though the passengers probably didn’t even notice).

Busy airports (and overworked controllers!) are definitely a safety challenge!

I think we are going to continue to see go-arounds in the news for the next month or two; in fact, there was one in the NY Times already that was really not very exciting but feeds into the idea that the air around the airports has degenerated into chaos.

I’m glad, at least, if this means more funding for controllers and runway/taxiway upgrades.

The shortage of air traffic controllers is not new, and Washington did address it last year:

( https://simpleflying.com/us-president-biden-aviation-safety-reform-law/ )

As President Trump signed a Federal hiring freeze on January 22nd, 2025, it was initially unclear whether ATC would be covered by its “public safety” exemption:

( https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-administration-exempts-safety-workers-air-traffic-controllers-resignation-2025-02-02/ )

Musk’s tweet, calling for retired controllers to come back, shows the new administration’s signature move of ‘two steps forward, three steps back’.

The White House was quick to clarify after the Washington mid-air collusion that it never the hiring freeze to extend to ATC, but a January 22nd memo explicitly targetted the FAA:

( https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/01/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-ends-dei-madness-and-restores-excellence-and-safety-within-the-federal-aviation-administration/ )

This essentially put every controller’s job on the line, without a clear path forward on how to replace those that failed this performance review. Some people argue that Trump’s actions did not affect the situation at DCA, but I can’t imagine that this attack on their job security did not stress traffic controllers at least a little.

(both from https://www.yahoo.com/news/elon-musk-genius-plan-solve-184117011.html )

Of the FAA’s 45,000 employees, many are support staff: someone needs to sweep the floor, screw in new light bulbs, or file paperwork. It’s probably obvious to everyone who’s read this far that 1) the FAA would hire every qualified controller they could get, 2) these controllers need a working organisation supporting them, and 3) within that support organisation, there are plenty of opportunities for DEI with no impact on air traffic safety.

When politics is ideology driven, it tends to miss the obvious, and does more damage than good.

[Note to Sylvia: You’re probably reading this in your moderation queue because I included too many links. That means you get to choose whether you want to have this political discussion in your comment section. ;-p ]

You’re writing more Why Planes Crash? Wonderful! They’re what I read – seriously – on flights. I find them soothing and reassuring.

Yes! It’s a bit weird to be 20 years back but also quite interesting to think about how the world has changed since 2004. Thanks for the encouragement! I did wonder if it was silly to go back to the series after all this time.

It’s not silly! Please go back and write more!

Yes ma’am! :D

Southwest pilot view video here. Remarkably calm when calling the go around.

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/mb-Rzxtq_mg

Should say, simulated video. With ATC on top.