Intolerable Risk: Dangerous Design behind the Washington DC Mid-Air Collision

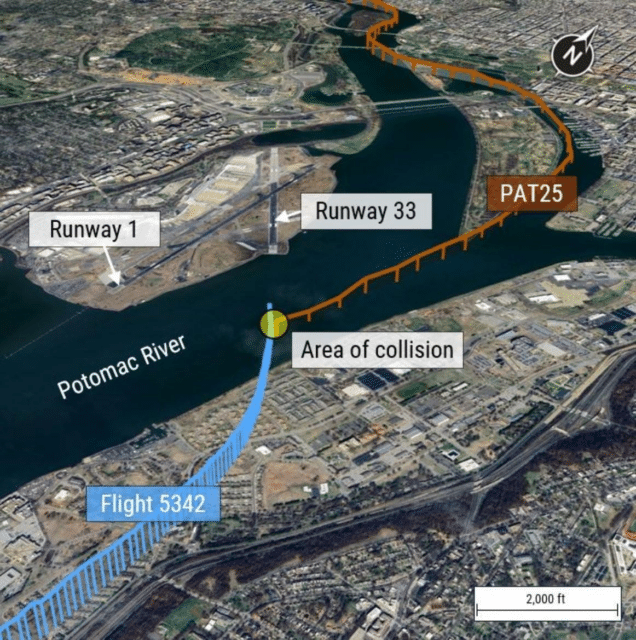

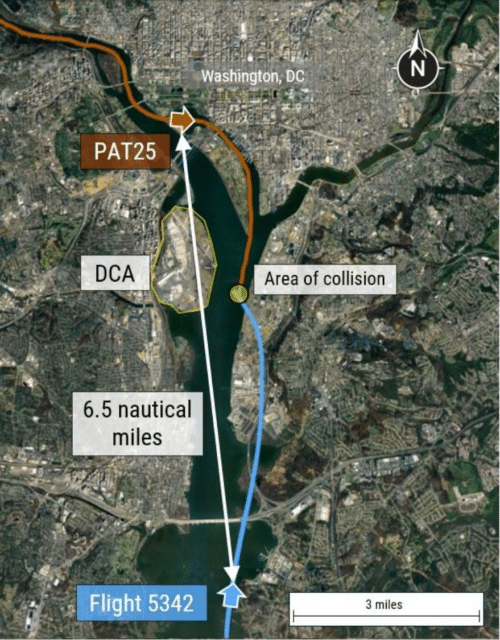

On the 11th of March, the NTSB released an aviation investigation preliminary report on the mid-air collision between PSA Airlines flight 5342 and a Sikorsky UH60L US Army helicopter. At the same time, they released an an urgent recommendation report calling for the FAA to close the helicopter route that the military helicopter was following whenever runway 33 is in use.

This report shows that the separation between the aviation traffic for runway 33 and helicopters on route 4 was dangerously tight. In short, this was an accident waiting to happen.

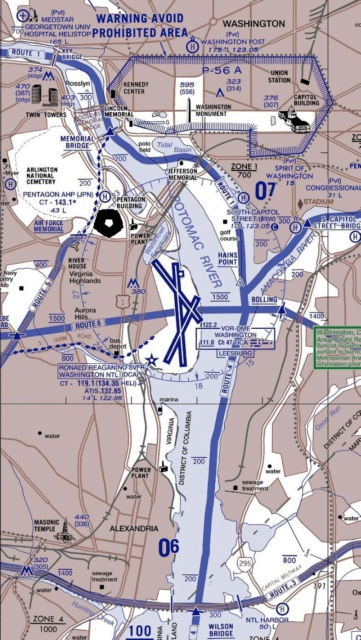

Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA) is located in Arlington, Virginia, five miles (eight km) from Washington DC. The airport has three runways: runway 01/19, runway 15/33 and (not relevant to this case) runway 04/22. The main runway in use at Washington National is runway 01/19 (north/south), a 7,169-foot (2185-metre) asphalt runway.

Runway 15/33 (south-by-southeast/north-by-northwest) does not have the landing distance of 01/19, with 5,204 feet (1,586 m) of asphalt. It is used for smaller aircraft and sometimes for overflow from the busier north/south runway. In addition, based on wind conditions, larger aircraft will specifically request runway 33, because the turn-off points are located closer to the terminals, which means less taxying to get to the gates. On busy days, runway 33 may be used to deal with heavy traffic and keep separation.

On that day, the 29th of January 2025, runway 01 was in use, allowing for northbound landing and departures. This means that arriving traffic is coming in from the south of the runway, with occasional traffic coming from the southeast and crossing the Potomac for runway 33.

There is a lot of helicopter traffic around the DC area, airspace which requires special approval as a result of the government sites and military bases in the area. Standard helicopter routes, first charted in 1988, have been defined for crossing the Washington DC airspace, numbered from 1 to 4. These routes have particularly low altitude restrictions to avoid conflicts with commercial aviation in the area. In New York, for example, the altitude restrictions range from 500 to 1,000 feet above mean sea level, while the DC area has maximum allowable altitudes as low as 200 feet amsl.

Route 1 starts at the American Legion Bridge near Cabin John, Maryland and follows the western shore of the Potomac until Key Bridge in Washington DC. Here, the route crosses the river to avoid prohibited airspace, following the eastern shore with the Kennedy Center and Lincoln Memorial visible to the east and Rosslyn to the west, to Memorial Bridge. From here, helicopter traffic must remain at or below 200 feet above mean sea level. The route continues south of the Washington Monument, where it leaves the river’s shore and crosses the Tidal Basin to follow the Washington Channel along East Potomac Park. Hains Point, at the southern tip of East Potomac Park, is directly across the river from the north end of Washington National airport.

Route 1 has two reporting points. Memorial Bridge, where the helicopter may cross to join Route 5 or continue to turn over the Tidal Basin, is a compulsory reporting point: pilots must report to air traffic control that they have reached that position as they follow the shore of the Potomac. Hains Point is a non-compulsory reporting point: pilots are not required to report passing the landmark, but the controller may request that they do so.

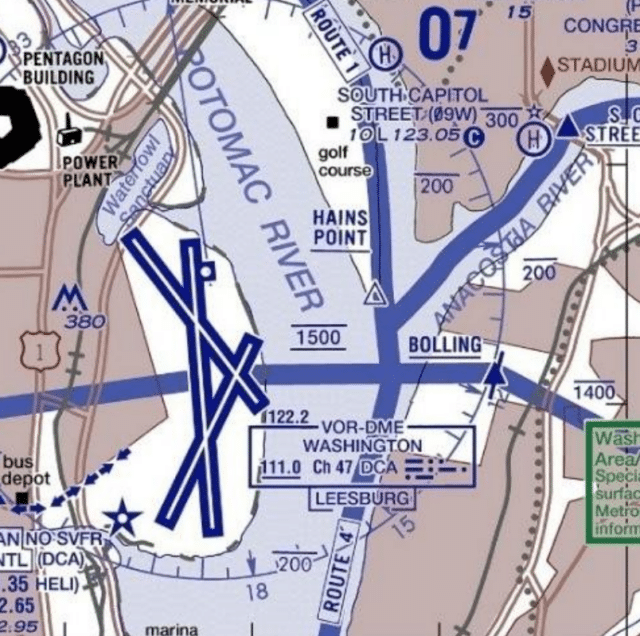

From Hains Point Route 4 continues south, parallel to the Potomac River and runway 01/19.

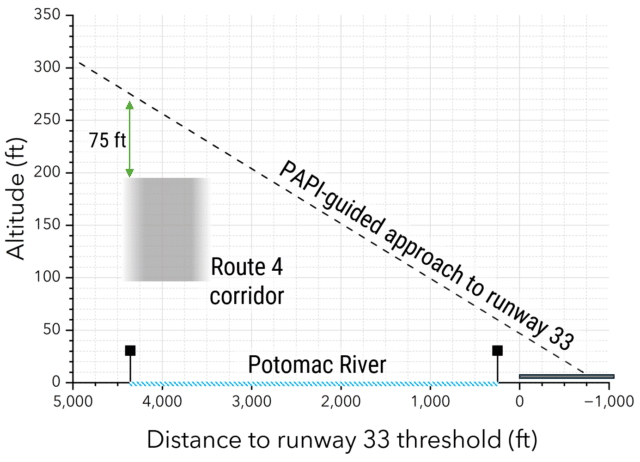

The FAA’s Helicopter Route Chart shows clearly that a helicopter following Route 4 would cross the approach path for runway 33. Vertical separation is accounted for by keeping the helicopter between 100 and 200 feet. An aircraft descending on a 3° slope would pass this point at 300 feet.

This does not offer a lot of leeway. A further issue at this intersection is that the fact that Route 4 follows the eastern shoreline of the Potomac, but there’s not a specifically defined distance that the helicopter needs to be from the shore. So a helicopter following the shoreline further over the water may have even less separation from the descending aircraft on finals for runway 33.

PAPI-guided visual approach to runway 33, according to FAA charts and aerial photogrammetry analysis.

This graphic from the NTSB shows how the vertical separation narrows. If everyone does everything perfectly but they arrive at the same lateral point at the same time, at best, the vertical separation is only 75 feet. If the helicopter is a bit further from the shoreline or a dozen feet above the maximum allowable altitude or if the aircraft is slightly below the 3° glideslope, the vertical separation becomes dangerously small.

The Swiss cheese model is used to show even with many layers of defence against accidents, each layers has flaws that, if aligned, can lead to the accident bypassing all defences. Looking at the helicopter route and the approach path for runway 33, we can already see the holes in the cheese lining up.

Now to be fair, aircraft are not usually arriving on runway 33. Over the period of the past six years, runway 01 accounted for 57% of all arrivals while runway 33 accounted for just 4%. Still, when the ATSB looked at the voluntary safety reporting program, they found a disquieting number of reports of near misses between helicopters and commercial aircraft, the vast majority of which were reported as on approach to landing.

There are a number of protections in place against mid-air collisions, including TCAS (Traffic Collision Avoidance System). TCAS is standard in modern commercial transport aircraft, with TCAS II _required _on all commercial aircraft in the US with more than 30 seats or over a certain take-off weight. TCAS is independent of air traffic control and serves to alert flight crew to the threat of collision when, for whatever reason, the standard systems have failed to provide the necessary separation. It scans all nearby aircraft and sounds a traffic advisory (TA) to alert the flight crew of nearby aircraft of potential conflict. The TCAS traffic display gives the flight crew a chance to locate the other aircraft visually and prepare for the next instruction. The next instruction if needed, would be a resolution advisory (RA), in which TCAS gives a mandatory instruction to the pilot, usually to climb or descend, in order to increase (or at least maintain) the amount of vertical separation between the aircraft.

The point is that once a resolution advisory is triggered, something has already gone wrong and the aircraft are already dangerously close.

When the NTSB looked at the near-miss data in the reporting program over the period from October 2021 to December 2024, they found over 15,000 cases where the lateral separation of less than one nautical mile and a vertical separation of less than 400 feet. Total operations for that period were 944,000 commercial operations (IFR departures and arrivals). Further, there were 85 records with a lateral separation of less than 1,500 feet and vertical separation of 200 feet. They discovered that every month, at least one aircraft TCAS resolution advisory was triggered by a nearby helicopter.

Here is another hole in the cheese. When an aircraft descends below 900 feet on final approach to land, TCAS stops issuing resolution advisories. This is for very good reasons: automatic commands to climb or descend could direct aircraft too close to terrain or into the path of airport traffic. At low altitudes, the system provides only traffic advisories without giving potentially dangerous instructions to climb or descend. Below 400 feet, even these audio alerts are silenced, to prevent distraction during this most critical phase of flight.

As Philippe explained in the comments of my initial piece:

I’m typed in the CRJ and I’ll have to correct myself regarding my last comment, as I’ve just read it up in the OM-B: While only RAs are inhibited below 1000′, TAs are inhibited below 400′ in descent (and 600′ in climb). Additionally, TAs are not created for targets below 380′.

The crew should have received a TA regarding the first inhibition (the A/C would have been above 400′ when the helicopter became an intruder), but as the collision apparently occurred at 200′, the helicopter would have been too low for a TA. Really a tragic event.

This means that this critical intersection of helicopters on Route 4 and aircraft on final descent to 33 did not have TCAS protection: maintaining vertical separation relied entirely on ATC coordination and visual separation, by design.

On that evening, the Sikorsky UH-60L crew filed a flight plan for a night flight from Davison Army Airfield for the pilot’s annual standardisation evaluation with the use of night vision goggles. The pilot was a captain with 450 total hours, 326 of which were on the same helicopter make and model. The pilot was accompanied by an instructor pilot, with 968 total hours, of which 300 were on type, and a crew chief, with 1,149 total flight hours, all of which were on UH-60 helicopters. The helicopter used the callsign PAT25.

At 20:33, PAT25 was 15 nautical miles northwest of Washington National Airport. The flight crew requested Route 1 to Route 4 before returning to Davison Army Airfield, which was approved by the controller. Note that there are two frequencies, one for the helicopter traffic and one for the commercial traffic, which were normally manned by separate controllers during the evening and then combined into one position after 21:30, when the traffic was not as heavy. However, there is a shortage of air traffic controllers at Washington National Airport (and most of the US air traffic control facilities). One news report said that the ATC unit there should consist of 30 controllers but in fact, there are only 19.

That night, one controller asked to leave early and the two positions were combined early. Thus, one controller was managing all of the helicopter and commercial aircraft traffic in the airport’s area during a busy time.

A CRJ700 operating as passenger flight PSA Airlines 5342 from Wichita, Kansas, was inbound to Washington National Airport. Both pilots in the CRJ held Air Transport Pilot Certificates. The captain, who had 39,050 total flight hours of which 3,024 were on the accident aircraft make and model, was the pilot flying. The first officer, with 2,469 total hours of which 966 were on the aircraft make and model, was the Pilot Monitoring.

About ten minutes after the helicopter started on Route 1, PSA Airlines flight 5342 contacted the tower controller to say they were 10.5 nautical miles south of the airport and on the Mount Vernon visual approach to runway 1. The controller asked if they would accept runway 33 for landing, which the flight crew was happy with. Having the CRJ land on runway 33 allows the controller a bit more leeway for managing traffic on runway 01. As Mendel explained on the previous post:

Scenario 1: Aircraft 1 (A1) lands on runway 01. It needs to slow down at the end of the runway, and then find a taxiway to get off the runway, before it is safe for aircraft 2 (A2) to land.

Scenario 2: Aircraft 1 lands on 33. Once it is past the intersection with runway 01, it’s safe for aircraft 2 to land on 33. The rollout etc. of A1 does not affect A2.

In scenario 2, the aircraft can be spaced closer and will still be safe from each other.

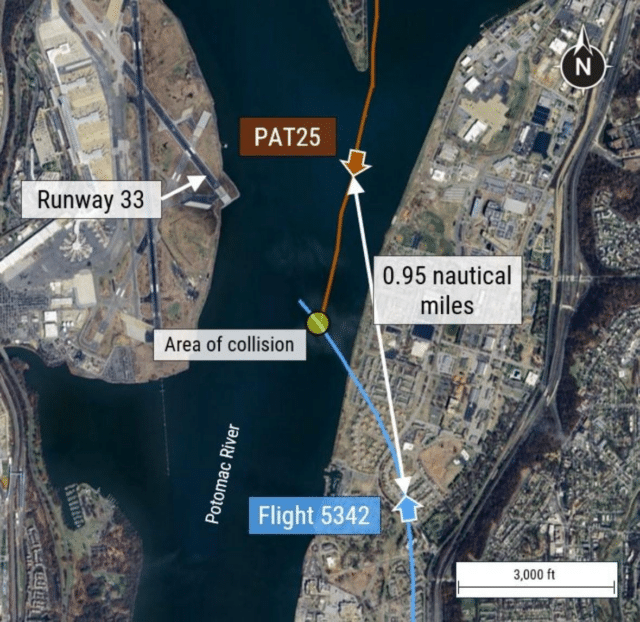

At this point, flight 5342 was travelling north along the Potomac River. The helicopter, travelling south along Route 1, was just crossing the Tidal Basin.

At 20:46, the controller asked the helicopter if they had visual contact with flight 5342.

Tower Controller: PAT25, traffic just south of the Woodrow Bridge, a CRJ at 1,200 feet setting up for runway 33.

Helicopter: PAT25 has the traffic in sight. Request visual separation.

Tower Controller: Visual separation approved.

Visual separation means that the pilot assumes the responsibility for maintaining a safe distance from another aircraft that they can see. This allows for less separation as well as reducing the controller’s workload. Requesting visual separation once you have the aircraft in sight allows for more flexible operations, as you can manoeuvre as needed to ensure that you don’t get too close.

The tower controller cleared a jet for departure from runway 01.

As the helicopter passed south of Hains Point, the controller asked again for the flight crew to confirm that they had the descending flight in sight.

Tower Controller: PAT25, do you have the CRJ in sight?

No response. About four seconds later, the controller checked in again with the helicopter.

Tower Controller: PAT25, pass behind the CRJ.

Helicopter: PAT25 has the aircraft in sight, request visual separation.

Tower Controller: Vis[ual] sep[aration] approved.

Twenty seconds later, at 20:47:59, at an altitude of 300 feet, the helicopter flew into the passenger jet. Both aircraft plunged into the Potomac, killing all crew and passengers on board.

Much has been made of the fact that the helicopter was 100 feet above the maximum allowable altitude. However, it is clear from this analysis that within the Washington DC airspace, aircraft and helicopters were placed on intersecting paths with minimal separation. Operations were designed with minimal safety margins, creating a system where pilots and controllers had to perform perfectly every time to avoid disaster. Controller staffing issues led to a reliance on visual separation during night operations in a situation where TCAS support was limited. The frequency of TCAS alerts and near-misses reveals this wasn’t an isolated incident but a predictable outcome.

Six days after the accident, the FAA restricted helicopter traffic from operating over the Potomac River near Washington National Airport. The current notice to airmen (NOTAM) (FDC 5/4379) holds until the 31st of March and if a helicopter must operate in that area (for example a life-saving medical flight, active law enforcement or air defence, or a presidential transport helicopter mission), then no civilian aircraft will be allowed to proceed through the area until the helicopter is clear.

The NTSB preliminary findings underscore this decision, showing that existing separation between helicopter traffic on Route 4 and aircraft descent paths for final approach on runway 33 are insufficient. In fact, the NTSB statement says outright that the existing situation poses an intolerable risk to aviation safety. They concluded that we simply cannot safely allow helicopter traffic on the existing Route 4 when aircraft are landing on runway 33.

The investigation is ongoing, however two urgent recommendations have been released asking the Federal Aviation Administration, primarily that helicopter operations on Route 4 be permanently prohibited between Hains Point and the Wilson Bridge whenever runway 33 is used for arrivals (and when runway 15 is used for departures).

Closing helicopter Route 4 when runway 15/33 is in use has a clear downside: this is a much-used corridor through the area. Losing it will cause issues for law enforcement and government operations (medical evacuation flights would not be affected, as they are always prioritised). Further, asking helicopters to hold for the corridor to become available also carries risk, notably in this case by increasing the controller workload even more.

Thus, the NTSB’s second urgent recommendation is for the FAA to devise an alternative helicopter route which would allow for travel in that area when runway 15/33 is in use and Route 4 is closed, allowing helicopter traffic to travel between Hains Point and Wilson Bridge.

and each aircraft’s approximate position

These recommendations acknowledge that safety systems must be designed to accommodate human factors and operational realities. Aviation has become remarkably safe precisely because of multiple layers of protection. However, care must be taken that this protection does not demand flawless execution: aviation safety requires tolerance for minor mistakes without catastrophic consequences.

This tragic accident revealed just how thin the margins for error had become around Washington National Airport. The helicopter routes designed almost forty years ago became more and more dangerous as aviation traffic intensified and controller staffing declined. The data showing monthly TCAS alerts and thousands of close encounters demonstrates that this wasn’t an isolated incident but a predictable outcome of system design.

The urgent recommendation from the NTSB targets the immediate danger. However, the fact remains this high-risk intersection was allowed to persist for years. As the National Airspace System grows increasingly complex, airspace design and controller staffing at busy airports must be reassessed to create breathing room for human error.

Thank you Sylvia for an excellent article. It was very informative and gives us plenty of food for thought.

Does the rec say anything about how they’re defining “in use”? The controller who redirected the CRJ was improvising; ISTM that arrivals on 33 or departures on 15 could happen at any time, meaning H-4 should never be open even before new routing is worked out.

An obvious choice would be to move H-4 a mile or more east — but that gets into an interesting class issue: that’s the poorest part of a generally poor city (most of the well-off live outside the boundaries, which can’t be expanded), and saying those people have to put up with noise for other peoples’ convenience (as used to be common when the highway system was being built) is no longer acceptable — especially when the well-off sections (mostly upstream from Key Bridge) get the noise abatement of making the helicopters fly over water instead of land.

I’ve read the report; it seems not to understand that ~5% use of 33 does not mean that the airspace around it is usable 95% of the time, given the random nature of that use. This idea clashes with the acknowledgment that making helicopters hold somewhere while waiting for the airspace to clear would be an additional load on ATC. I wonder whether anyone actually looked at the whole report, especially the distribution of usage, and bothered to put 2 and 2 together?

There’s one other rerouting that might be satisfactory: from Hains Point, take Route 6 across the center of the airport, then a new route along the rail line that runs south by west from the airport to Alexandria. This line is used by rapid transit (note the M-in-a-square at intervals on the Google “satellite” view (sample link below), so there’s some noise there frequently for 18+ hours a day. The line passes a highway stub that connects to I-495, which lies under Route 3, which connects to route 4 at the Wilson bridge.

sample link: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Ronald+Reagan+Washington+National+Airport/@38.8338498,-77.046774,1801m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m6!3m5!1s0x89b7b731402fe095:0x4168af016d076bad!8m2!3d38.851242!4d-77.0402315!16zL20vMDE4c3Ey?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDMxOS4yIKXMDSoJLDEwMjExNDU1SAFQAw%3D%3D

One hole in the cheese lining up was this:

The Blackhawk’s voice recorder (CVR) indicates that the crew did not receive key information from ATC that would have helped them understand the situation. ATC initially described the CRJ as “circling” to land on runway 33, but on the helicopter CVR it’s not audible. Equally, the “pass behind the” CRJ 20 seconds before the collision was stepped on; the crew thought tower wanted them to keep to the left. If they had heard these words, they would’ve been more aware of the situation, and should have expected the CRJ to cross in front of them.

To visualize how little space 75 ft is, the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco has 220 ft. clearance at high tide. If you space them only 75 ft. apart, you can easily fit a helicopter and a jet on top of each other under that bridge.

Crikey, that’s a heck of a visual aid )the Golden Gate bridge example). Can’t imagine anyone would think that was acceptable.

I feel awful for the crews and passengers; they did not deserve this. Looks a lot like a classic normalisation of deviance crash.

side note: my local paper, being a few weeks behind, just reported the death (last month) of the creator of the Swiss cheese model:

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/13/science/james-reason-dead.html

is interesting, including the story of what put him on to the idea.

Another update: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/27/us/politics/reagan-crash-faa-rule-change-broadcast-positions.html

The beat goes on.

Helicopters and their routes aren’t the only problem: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/29/us/politics/faa-dca-delta-air-force.html

(The story is very short on detail; my guess is that the T-38 group was using a river route for noise abatement, just as flights into and out of DCA do.)

They were flying across the airport, and according to ADS-B data, the minimum separation reduced to 100 feet vertical and 0.7nm horizontal (avherald). It looks to me like they’re one runway length apart as Delta 2983 was climbing through 1000 ft, with the T-38 formation at 1000 ft pointed right at them. See https://www.youtube.com/embed/bPQjQ23YTJo .

What puzzles me is this, from https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/statements/accident_incidents :

The ATC audio shows no corrective instructions, and none should be given when a TCAS RA is active.

And sometimes people are just stupid: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/30/us/kite-plane-ronald-reagan-airport.html?unlocked_article_code=1.8E4.AsRr.lPEFYo_Fvvb8&smid=url-share

(summary: someone was flying a kite where kite flying is explicitly prohibited, in a park very close to DCA.)

The Times has another summary from its investigation: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/27/us/politics/takeaways-investigation-airport-collision.html

Some bits of data that may not have been reported.

NB: above is a summary that AFAICT doesn’t link to the full article at https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/27/business/dc-plane-crash-reagan-airport.html?unlocked_article_code=1.DE8.mYwx.mnOHhfFKLmD6&smid=url-share (long link gets around paywall). Interesting points left out of the summary include the FAA’s admission that tower staffing was “not normal” when the collision happened (Reagan v. PATCO: the gift that keeps on taking) and that the copter had shut off a once-per-second reporting system as part of its “simulation” of an evacuation, leaving ATC relying on a transponder that answered less frequently. How many holes are going to be found in this cheese?

Another incident, from a helicopter flying a different route: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/02/us/politics/reagan-washington-national-airport-helicopter.html

The US Congress is holding 3 days of hearings; updates at https://www.nytimes.com/live/2025/07/30/us/dc-plane-crash-hearing#ntsb-hearings-dc-plane-crash. Latest hot data as of ~10:30 EDT: “N.T.S.B. experts just explained why the helicopter might have been flying at such a high altitude in the moments before the crash. In testing, they found that the altimeters — the devices that tell pilots how high off the ground they are — in Black Hawk helicopters could have a discrepancy of as much as 130 feet when flying over the Potomac river.” (IIRC, that’s more than the discrepancy between the altitude the copter should have been at and the altitude it was at.) Maybe this will spur some of the people that a helicopter on a live run (as opposed to this practice run) to push harder for safety standards.

And somebody tried to give the military a pass to go back to its old ways; https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/10/us/politics/ntsb-defense-bill-dca-crash.html reports the NTSB head denouncing the current military appropriations bill for removing rules added after this crash. A key quote: “The section at issue would create a waiver allowing military aircraft to turn off their enhanced tracking software while flying on national security missions through parts of the Washington airspace, or if the military determines that the flight poses no risk to commercial flights.” — as if the military is going to know enough about commercial flights to make such a determination….

The Senate has blocked this provision: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/17/us/politics/senate-defense-bills-air-safety.html. (In a previous story, Senator Cruz (R-TX) was going to hold up the entire bill if this wasn’t fixed; normally I don’t have much time for him, but this is praiseworthy.) Now the House has to act, preferably before going on holiday….

And now we hear that the battalion the helicopter came from was a trouble spot for years, including other near misses: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/19/us/politics/army-washington-dc-airspace-helicopter-crash.html

The Washington Post has a simulation of what the helicopter pilot would have seen; between city lights and a larger plane behind the CRJ, it’s a mess: https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/interactive/2025/dca-crash-cause-lights/

The FAA says the restrictions on helicopters around DCA will be permanent: https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/22/us/politics/helicopter-restrictions-washington-crash.html. The rule specifically says that routine training is not an allowable exception. We can hope there won’t be another such collision.

The NTSB publicly reams the FAA but has blame left over for other parties: https://apnews.com/article/dc-plane-crash-army-helicopter-ntsb-cause-c2ebc159a163068b782dd4824097b00b

I appreciate your updates to this! I have been trying to keep up with the NTSB releases this week but it’s been a struggle.