ICON A5 mountain crash

On the 8th of May 2017, an ICON A5 aircraft crashed into Lake Berryessa, California, after attempting to turn away from rising terrain. The pilot was an engineer and test pilot for ICON aircraft and very experienced. He and his passenger were killed on impact.

It’s a relatively familiar mountain-flying story, an aircraft boxed in and unable to climb away from the rising terrain.

The NTSB final report was completed in just three months. What interested me was a witness account which showed, I think, how an accident like this looks from the outside, to someone not quite as obsessed with aviation as we are.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be:

The pilot’s failure to maintain clearance from terrain while maneuvering at a low altitude.

Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s mistaken entry into a canyon surrounded by steep rising terrain while at a low altitude for reasons that could not be determined.

The Icon A5 departed from runway 2 at Nut Tree Airport in Vacaville, California at about 9am that morning and flew north as it climbed to 3,700 feet GPS altitude. About 15 minutes after departure, the A5 started a descent and as it crossed the shore of Lake Berryessa near the Monticello Dam, it continued to descend to 450 feet (137 metres) GPS altitude.

GPS altitude is the geometric altitude above mean sea level, as opposed to pressure altitude which is a conversion of pressure to altitude based on changes from the average surface pressure at mean sea level. GPS altitude requires the GPS receiver antenna to have four working satellites in view, where one is overhead. GPS altitude is accurate to within ten to twenty metres (30-65 feet). It is more reliable than pressure altitude and probably at least as reliable than Joe, who saw the A5 that day.

Joe has a boat and he likes to go fishing. On that day, Joe and his friend Preston took the boat on a trailer to Pleasure Cove Marina for a day of fishing on the lake. They were just getting set up when a plane flew past, low enough for Joe to wave at the pilots and to see the pilots wave back.

I’ll let Joe tell you about it, because honestly, I kinda love Joe.

I saw the plane approaching us from about 300 feet away at approximately 30-50 feet off the ground. As the plane passed I waved to the pilots and they waved back.

Lake Berryessa has a surface elevation of 443 feet and the aircraft’s GPS elevation was around 450, so although it’s within the margin for error, I suspect 30-50 feet off the ground is a bit generous.

Everything at that moment seemed normal. The plane had no smoke coming from it, the engine was running smoothly and it appeared as if they were just cruising the lake or coming into land the airplane.

The ICON A5 is a two-seater amphibious light sport aircraft which has only been in production for about five years. ICON Aircraft was located in Vacaville and the A5 was regularly seen in the area, which is probably why Joe thought it might be landing on the lake. Being able to see the pilot wave at you must have seemed a bit odd but Joe didn’t dwell on that. The A5 flew past and the men got down to serious business.

We had just begun fishing… my friend Preston was baiting his line and I turned back to watch him when I heard the airplane’s engine rev up and accelerate hard as he pitched the plane upward toward the right side of the Little Portuguese Canyon first hill, in what appeared to be an effort to climb out of the cove.

(I can almost imagine the NTSB investigator trying to get all the details. NO ONE CARES ABOUT PRESTON’S BAIT, JOE.)

I continued to watch the airplane as it reached approximately 100 feet above the ground and all of a sudden turned left (west). The airplane continued left and began to quickly descend towards the ground as if he was trying to make a U-turn in the air. I lost visual as they flew behind the point in which our boat was sitting on the point of Little Portuguese Canyon. Within three seconds both Preston and I heard a very loud crash and we instantly knew the plane had gone down.

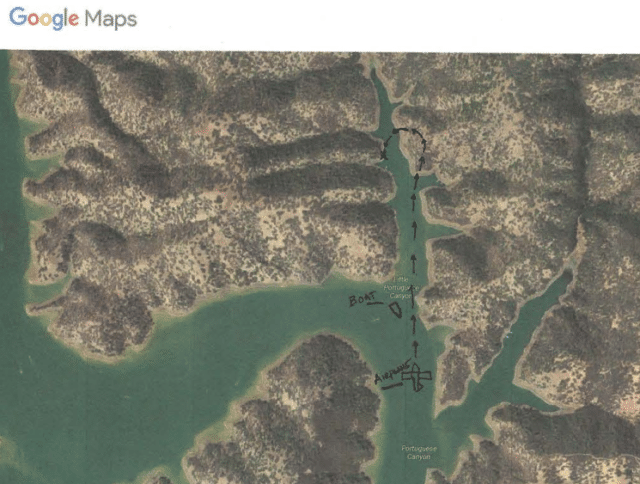

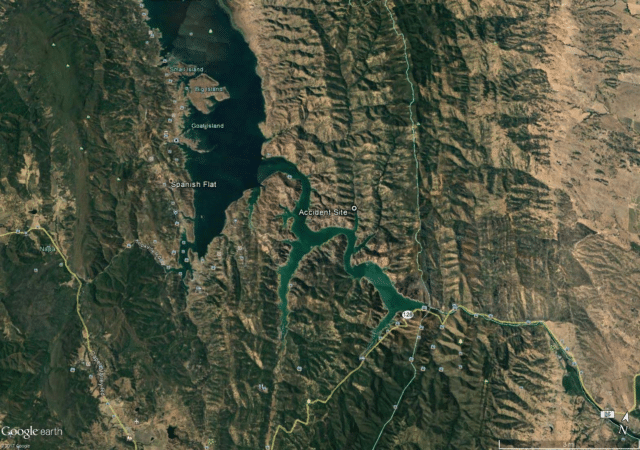

Here’s a shot from Google Maps showing the accident site. You can see Little Portuguese Canyon north of the accident site: it narrows very quickly and is surrounded by high terrain. It’s definitely not somewhere you want to fly into and especially not at 30-50 feet above the lake while waving at fishermen.

The flight data backs up Joe’s impression: the A5 entered the canyon and then increased power. The aircraft began to climb as it started a left turn to the west, reaching an altitude of 506 feet GPS altitude, which was about a hundred feet above the water, before beginning to descend. It crashed into terrain travelling at 66 knots indicated airspeed at a GPS altitude of 470 feet.

The rising terrain around Little Portuguese Canyon ranges from 780 to 1,420 feet above mean sea level. At a peak GPS altitude of 506 feet above mean sea level, they never had a chance.

We quickly reeled up our rods and drove the boat over to them as fast as we could as we approached the airplane on the left side embankment of Little Portuguese Canyon.

![]()

It’s pretty clear that there was nothing to be done but they called out “Are you okay? We’re here to help you,” and waited for a response. Preston volunteered to climb over and look in the cockpit, telling Joe to keep a safe distance. Once there, Preston confirmed that they were crushed into the cockpit and more worryingly, that he could smell gasoline. He jumped back into the boat and they raced back to find help. Preston tried calling 911 while Joe phoned the marina but they had no coverage and couldn’t get through.

About halfway back, Preston finally managed to connect to 911 but was struggling to hear the dispatcher. Joe got through to an answering machine at the marina.

At approximately 0924 hours according to my cellphone log, I called Pleasure Cove Marina and the phone rang and went to an answering machine in which I started to leave a message stating “We have an Emergency, a plane has crashed with two men down and they need help!” A woman picked up the phone and said what happened, where are you at? I informed her of the situation and told her we were on the way to her Marina and needed all the help we could get …

She told me to call 911, I told her no, you call 911 as our reception is bad and Preston was having problems hearing the dispatcher on his phone. She said hold on don’t hang up and said she was calling from a different phone.

The accident site was not reachable by road and a boat was quickly manned to follow the fishermen to the site. The final report doesn’t include details of the attempted rescue but it is clear that the two in the aircraft never survived the initial impact.

Joe and Preston led the marina workers to the beach where the plane had crashed.

Once the Pleasure Cove Marina workers arrived to the beach they approached the two men and saw that they were not moving or responding to them. They got back on their boat and began to wait in the middle of the cove for the authorities to arrive. We waited with them for approximately ten minutes. The Pleasure Cove Marina workers told us we could leave as we did not have to watch this, we asked them if they were sure and they said yes, so we left.

They didn’t leave the lake, mind you. I presume they went back to fishing.

Later that day, as we came back to the dock and loaded the boat on a trailer a Napa County Sheriff asked us if we saw a plane crash today and we replied yes. Sheriff asked us for our information and if we could stay to answer questions and I said sure, anything to help you as I approached his vehicle. Sheriff contacted someone out at the scene and asked if he wanted us to wait and he replied no I am finishing up here and will call them later. We drove home and once I got home at approximately 2013 hours I spoke to you (Josh from NTSB) and told you the very sad story of what we observed earlier that day.

I don’t know if they caught any fish but Joe finished his report by drawing a picture of what happened. It is adorable but, more importantly, shows just how easy it could have been to fly into the wrong canyon, missing that left hand turn that would have taken them to the open area of the lake.

It is tragic and I hope I don’t come across as dismissive. But there was something charming about Joe’s story of going fishing on the lake that day that made me want to share it. It helps me to remember that there are real people involved on a number of different levels.

You can read the final report as NTSB reference WPR17FA101; it’s only eight pages.

Sure looks like waving at the friendly fishermen distracted the pilot from making the necessary left turn.

That’s my suspicion as well

The way this man Joe tells his story is touching. Obviously he is a kind and intelligent man. His observations have been confirmed by the facts that have become known. Which is remarkable. If we read over other the reports of witnesses to other accidents, in many cases they diverge and give very different accounts of the same accident.

What strikes me in many of these stories is that technology seems to be replacing basic air(wo)manship. Which can have deadly consequences if the technology is available, but not used. Sylvia mentions GPS altitude. In my early days of flying, GPS had not even been thought of by writers of science-fiction.

One incident that comes to mind is the one that caused the death of Neil Williams. He was perhaps one of the most gifted pilots of his time. He instructed aerobatics at the Tiger Club in Redhill. The aircraft used was a Stampe SV4. I took a few with him. He did not think much of my progress, in my defence, I could only take lessons on the relatively rare occasions when I was visiting Redhill and he had a slot available at the same time.

Anyway, Neil was a Royal Air Force fighter pilot and an aerobatic ace. Flying at knife’s edge, at the very limits of the capacity of the aircraft, sometimes even what can be called beyond, and his own – extremely high – abilities was second nature, and it became his downfall.

He was also a demonstration pilot with the Shuttleworth Collection and one of the few, perhaps the only pilot who was cleared to fly all types in that famous flying aviation museum.

They had acquired a Casa, a Spanish-built twin, I believe a copy of the WW2 Siebel, used to transport German generals. During the Franco era Spain used aircraft that were either bought, or were built under licence from Nazi Germany. This was the last still airworthy example.

It took place sometime in the ‘seventies. Neil was flying it to the UK with his wife Lynn, herself a very accomplished aerobatic pilot, and a mechanic. The Siebel (or it may have been a Heinkel, very similar) was not equipped for instrument flying.

In the north of Spain the weather was very poor. They had to cross the Pyrenees mountains and local pilots apparently advised them not to go.

But they did and, in deteriorating conditions of visibility, entered a valley. It seems that they mistook the one for another that would have enabled them to fly through it. They found themselves facing a dead-end. In a last-moment attempt to turn back, a wingtip hit terrain and not even Neil’s extraordinary skills could save them.

A tragic end of a pilot who had become maybe too used to flying without any safety margin, instead relying on proven, exceptional skills that under the same circumstances would have killed every other pilot, like walking away from an aircraft that broke a wing in-flight during an aerobatic training session.

A pilot should never be so distracted waving to people that he flies into terrain. He was already very low. Had he intended to turn left and land? In that case – I don’t want to put blame on someone who loft his life, but… – he should have been concentrating on his landing (on the lake of course). This would have required a turn towards the lake and, already at a dangerously low altitude, should have required all his attention.

I made a mistake about the aircraft Neil Williams was killed in. It was a Casa-built Heinkel 111 transport. When I took my first flying lessons at Hilversum, the Netherlands, a local banner-towing and sight-seeing company called Skylight had bought a Siebel 204, registered PH-NLL.

They had intended to start air taxi and sightseeing operations, replacing an old Fairchild single engine aircraft, but awaiting the certification they parked it as an eye-catcher in an area accessible to spotters.

The paperwork for commercial operations did not materialise, and it did not take long before the aircraft had been vandalised beyond hope of repair. The wreck sat there for a few years, but it became a hazard and had to be scrapped.

It bore some similarities with the Heinkel, especially the bulbous all-glass nose, but the Siebel had twin tailfins, like the Beech 18.

Oh, of course when mentioning that a pilot should not be distracted by waving to people, I meant of course the pilots of Sylvia’s accident report.

Was there anything preventing the pilot from landing in the canyon? The A5 is amphibious, after all, and may have been headed for the seaplane base on the lake. It seems to me that attempting a water landing would have produced a better outcome than the aerial U-turn.

Common sense dictates that flying low in mountainous terrain is dangerous. Yet the pilot felt safe doing so, perhaps because they planned to follow the water onto the open lake; with that plan, there wouldn’t be any obstacles to crash into.

But the big fallacy about safety is the idea that you’re safe if nothing happens under normal circumstances; but you’re really only safe when you can cope with a mistake being made or a plan going wrong. If you can’t recover from a mistake, your safety was an illusion.

I agree. Even if he had run out of water to land on, it would have been survivable.

The problem is that he had a split second to make a decision and he was presumably already disorientated by not being where he expected to be. In that split second, he made the wrong decision.

I agree with Harrow that waving at the fishermen probably distracted him; he was 30ft above a lake with high ground all around. The last thing he should have been doing is waving.

Cliff, your observations make sense but: how much water did they have ahead? And to what extent did the area create a false illusion?

I remember a landing at a strip in the south of the UK. It was a former WW2 bomber base. The runway had been shortened by half, with a barrier at the end. But it still had the original width. It was dusk, the runway looked much shorter than it really was.

I was not the flying pilot. After touch-down my colleague pulled the power levers in revers, so hard that he activated a safety device in the tail cone nicknamed “mousetraps”. This resulted in a total engine shut-down. We coasted off the runway and came to a stop on the taxiway.

A mechanic had to be called out to reset the system. Our major problem was customs and excise. This airport had customs on prior request so they were waiting for us.

And the aircraft came to a halt not far from a fence that separated the airport from the public road. Worse: there were bushes and small trees lining the perimeter fence. And so we were arrested on suspicion of having engineered this incident to use the darkness to thrown “something” over the fence. Fortunately, it was soon cleared.

In our case, the optical illusion of having less distance ahead for a safe landing than we in reality had led to a funny incident.

Can it be that the pilot, seeing the terrain rise in front of him, could not have realised how much room he still had available and decided to make a steep, low level turn? Or maybe he really did not have enough space any more?

I found the “Pilot’s Operating Handbook; ICON A5; ICA012347 Issue A3; 2018-08-22 – ICON Aircraft” online. The performance section says on page 87 that the A5 needs about 2100 feet for a water landing after passing a 50 ft obstacle at 50 KIAS. The crash site is just under 2000 feet from the end of the inlet, and by all reports they weren’t even 50 ft up. But the manual also says a water landing requires glassy water and zero wind. The NTSB report says the wind speed was 5 knots from 30 degrees, but I expect conditions may have been more favorable at the bottom of the canyon; had there been 5 knots of wind at the surface, the waves might have been 6 inches high. And if you overlook a floating log, that’s bad, too.

The manual contains an emergency procedure for “box canyon reversal”, but doesn’t say how much space is required to pull it off.

This Icon A5 had a ballistic parachute installed, but the accident aircraft was too low to use it effectively; I believe it wouldn’t have unfolded properly if it had been deployed.