“Completely Uncontrollable” : Air Astana flight from hell

On the 11th of November, an Air Astana ferry flight out of Lisbon almost ended in tragedy. The ATC recordings are almost unbelievable and I recommend listening to the whole thing (audio and transcripts are below but if you are reading this as an email, you may need to click through to the post to get them).

Air Astana is the flag carrier of the Republic of Kazakhstan which operates out of Astana International Airport and Almaty International Airport.

In 2009, an audit by the ICAO found that the Kazakhstan Civil Aviation Committee (CAC) to be non-compliant when it came to regulatory oversight. As a result all Kazakhstan-registered airlines were banned from flying to, from or within the European Union with the exception of Air Astana, whose aircraft were registered in Aruba and who presented a strong operations safety management programme. Air Astana was the only Kazakh airline to fly to the European Union until the ban was lifted in 2016; however only their Boeing and Airbus fleet was allowed to operate in the EU until December 2015, when the restriction on their Embraer aircraft was lifted.

The Portuguese Aviation Accidents Prevention and Investigation Department (GPIAA) released an information bulletin on Tuesday, which is where I have picked up the sequence of events.

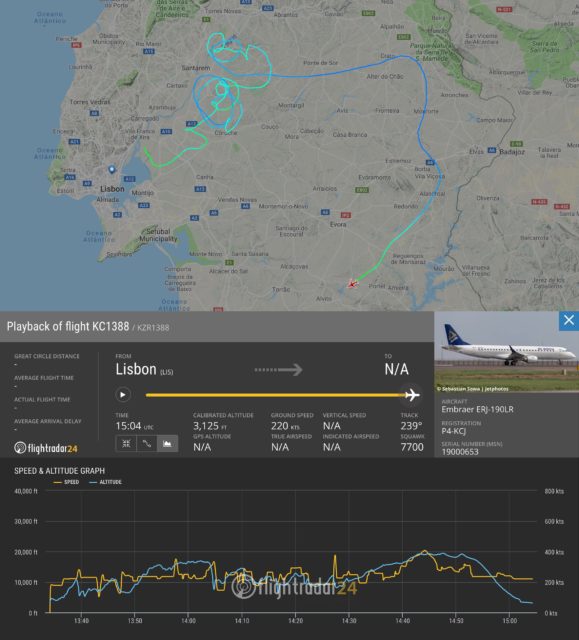

The aircraft was a five-year-old Embraer 190 registration P4-KCJ which had undergone maintenance at Lisbon aviation technical centre (C-check).

Here’s the first half of the ATC audio and transcript by VASaviation.

At 13:33 local time (GMT) the aircraft departed Alverca do Ribatejo airbase for a ferry flight to Almaty, the largest city in Kazakhstan, with a scheduled stop at Minsk, Belarus, for refuelling. There were three flight crew and three technicians on board the flight.

The weather was poor, with thunderstorms in the area. This is apparently an animation of the weather at the time of the flight:

Immediately after take off, the flight crew found that the aircraft was not responding well. The wings began to oscillate. They attempted to counter the oscillations but without knowing what was causing them, the flight crew were only able to minimize the oscillatory movements. They became concerned about the high structural loads they were imposing on the aircraft.

They declared an emergency and requested a return to the airport while struggling to gain control. There were no malfunction indications other than the continuous alerts for abnormal flight attitudes.

The controller asked them to descend to 2,500 feet but the flight crew responded with “Negative”. From there, the flight control issues can be seen simply by looking at the flight path.

The crew repeatedly lost control as they sustained intense G-forces. They requested vectors out to sea so that they could ditch the aircraft there. However, they were unable to keep to the headings. All the while, the three crew worked together and with the technicians on board in order to troubleshoot the issue and find some plan of action. Flying through a thunderstorm, they could not find any other option than to ditch, while ATC informed them that they would not reach the sea but could attempt to ditch in a river.

To follow along, here’s part 2 of the VASAviation ATC transcript:

They deactivated the flight controls direct mode, removing the Flight Control Module from the flight surfaces command chain, taking direct control of the elevators, rudder and spoilers. This improved their control however they were still struggling to control the aircraft roll-axis and ATC warned them that they were flying away from the sea and into Spanish territory.

It became clear that the ailerons were behaving erratically: by avoiding their use, the flight crew could keep the roll to a minimum. They were finally able to control the aircraft’s altitude and heading and flew east to find better weather and visual conditions. A pair of F-16s from the Portuguese Airforce flew alongside them to guide them south to Beja airport, about 125 km south-east of Lisbon.

The flight crew broke off the first two approaches for runway 19R, the first for not being aligned with the runway and the second as they were too high. On the third attempt, they were unable to control their drift but successfully landed on the left runway (19L) at 15:26.

After two hours of struggling, they were safe on the ground.

One of the passengers suffered a leg injury and all of them were physically and emotionally shaken. Two of the crew were taken to Beja hospital to be treated for shock.

Here’s a video of the landing, taken by one of the F-16s:

And one more video, taken from the ground as the aircraft came in on its final approach:

The Portuguese Aviation Accidents Prevention and Investigation Department (GPIAA) is holding the aircraft pending further investigation. Embraer and Air Astana have sent specialists to support the investigation. The initial evidence points to a failure of the “aircraft roll controls configuration” which probably took place during the maintenance. This sounds to me like cables were crossed, resulting in reversed controls.

Whatever the issue turns out to be, that was an amazing job carried out by the flight crew for an incident that could easily have resulted in a crash directly after take-off. When I saw the video of them landing, I wanted to applaud.

The ailerons of modern jet transport aircraft are not controlled by cables that can be cross-connected. I don’t know anything about the Embraer except that it looks a bit like a small 737.

But judging from the available information, it would seem that something has gone wrong during the maintenance.

The crew apparently kept working as a team (pointing to excellent CRM !!!) and they managed to bring the aircraft to a safe landing.

So: well done. Another :-) ending !

I struggle sometimes with *why* planes fly; mechanics are largely wasted on me. The Embraer 190 flight controls are fly-by-wire but page one refers to cables:

http://www.smartcockpit.com/docs/Embraer_190-Flight_Controls.pdf

“The ailerons are driven by conventional control cables that run from each control wheel back to a pair of hydro-mechanical actuators.”

So is there a way of ensuring that they can’t be cross-connected or am I misunderstanding something?

I work with EMB 170s and if I remember correctly all the flight controls except the ailerons are fly by wire and the ailerons are indeed driven by actual control cables.

Unfortunately I don’t understand much more about the mechanics of that either.

That fits with what I read; thanks!

I noticed the long shot showed the plane wobbling a little on approach, but the off-the-wing shot looks like they greased the landing. (I do wonder how someone in the position of one of the chase planes had spoons to shoot that video and keep flying — do Portuguese F-16’s come with cameras mounted?) That was amazing after everything they’d been through.

I presumed mounted cameras but now that you’ve mentioned it, I do wonder!

That is the TGP (targeting pod) usually carried on one of f16 fuselage stations. It is capable of visual and IR tracking of both ground and air targets. The images are shown to the pilot on the MFD.

Holy lord how many times did these dummies need to ask for vectors to the sea. It’s a country surrounded on two sides by the sea lol. They have maps. How did they get their licenses?!

I think you underestimate the amount of pressure and stress in this kind of situation. They certainly didn’t have any time to start looking at maps!

They were in IMC with a completely uncontrollable aircraft battling immense G forces. It is a miracle that they even survived. Your comment is foolish and very disrespectful. These pilots are heros.

This is seriously disturbing. Two things: does no-one do a full controls check that left aileron actually gives left aileron? Etc. But more to the point, I really think there should be a big red button that deactivates all automation and gives direct control to the crew. Or something similar. Look at Lion Air, the Air France accident over the Atlantic. We need a return to basic airmanship and less computer games.

I’m not sure about an ailerons control check but some of these issues are tough to spot on the ground. Clearly the aircraft taxied fine, else they wouldn’t have made it to the runway. But more importantly, automation wasn’t the problem. The crew, controlling directly, could not gain control of the aircraft until (it seems) they stopped using the ailerons in any way and instead used pitch and rudder only.

How direct control do you want? Even the EMB-190 has (per Sylvia) hydraulic actuators rather than a physical connection, suggesting that it’s too big to be steered by human muscle; as we see here, physical connection to the boosters only works if all the parts are working. I suppose that in theory a plane could be built with physical connections overseen by software, but that would be heavier and have more room for glitches (since there would be two systems for each surface rather than one). And wrt the Air France case, the Wikipedia summary says the autopilot shut down because it couldn’t cope with a frozen pitot tube (cf last week’s item involving a covered static port), leaving the pilots to guess (wrongly) what to do.

As for control-surface checks: the ailerons \\might// be visible from the cockpit; rudder and elevator aren’t. In theory every commercial flight could require someone outside to report what happens when the PF moves the controls before leaving the stand — but that’s one more complication at a complicated time.

“For every problem there is a solution that is simple, easy … and wrong.”

And Sylvia’s description says “They deactivated the flight controls direct mode, removing the Flight Control Module from the flight surfaces command chain, taking direct control of the elevators, rudder and spoilers.”, so whatever computer “games” they had were out of the picture.

I learned something new.

The one larger jet that I flew was the BAC 1-11. The controls were hydraulic. The Corvette had cables, augmented by roll spoilers. Still, knowing little or nothing about the finer works of the Embraer, it would seem that the forces acting on an aircraft that size would need something to help the pilots. Otherwise the aircraft would either be very, too slow, to respond to the controls or the pilots would need the build of Schwarzenegger in his younger years to be able to control the aircraft.

So, but this is a blind guess: Does this aircraft have control cables but with some form of power assist, perhaps electric?

The 1-11 had a system where the hydraulics could be bypassed, e.g. in the event of a fluid leak, and coupled for manual control: “manual reversion”. It required a lot of muscle to operate the aircraft in manual mode.

The Corvette had a disconnect of the roll spoilers. All it needed was a rather hard movement of the ailerons against the stops. Again, it was a bit harder to control the aircraft.

To me it would seem that the crew of this flight did manage to disconnect the power assist. Which would suggest that perhaps an electrical circuit had been connected the wrong way around????

So: In that case (pure speculation here!!) the cables would have been connected properly, but the power assist would try to “help” by giving an opposite input. And not until the electrical (speculation again !!) power assist was disconnected did the crew regain proper control.

Again, I must stress that I am voicing an opinion that may be totally wrong.

But one thing still holds: the crew did an excellent job !

PS a full control check is normally done prior to every flight, more so when just out of maintenance. Bigger transport aircraft taxi with the gust lock ON. If the pilot forgets to remove it, a configuration warning will alert him or her when power is advanced for take-off.

The “controls – full and free” is normally of course done with the line-up checks.

Are they checking only that the controls move freely, or that the controls move the surfaces as expected? If the latter, who’s watching the tail and reporting to the flight crew? I don’t recall ever seeing a large plane with a side-view mirror reaching out enough that crew in the cockpit could see the tail.

As Sylvia showed us a few years back, gust-lock warnings aren’t always heeded; see https://fearoflanding.com/accidents/accident-reports/how-to-drop-a-gulfstream-iv-into-a-ravine-habitual-noncompliance/ (although the warning may have been muted because the designer mistakenly thought his connection between the gust lock and the throttle was enough to prevent getting anywhere near takeoff speed).

im just going to mention, that was one fidgety filmer, that camera was all over the place, XD