Wings Over Dallas: How Poor Systems Led to Mid-Air Collision

On the 12th of November 2022, a Bell P-63F Kingcobra fighter flew into a Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress bomber during the Wings Over Dallas airshow. All six crew members in both aircraft, five in the Flying Fortress and one in the Kingcobra, were killed in the collision.

I wrote about the background of the two aircraft when the accident happened. Now the NTSB has released its 94-page final report, with a detailed analysis of what happened that day.

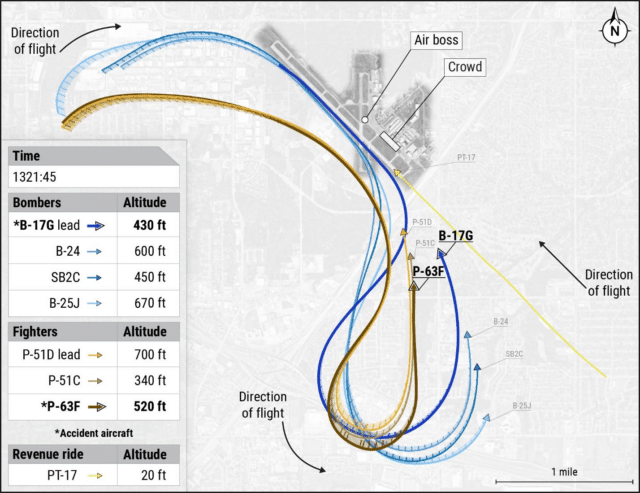

The demonstration at the airshow consisted of two groups: the bomber group and the fighter group.

The bomber group consisted of five historic bomber aircraft, with the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, a World War II bomber known as Texas Raiders, in the lead.

The fighter group was led by a North American P-51D Mustang in the lead, followed by a P51-C Mustang in the number two position. The Bell P-63F Kingcobra was in the third and final position.

Other aircraft were active during the demonstration, including a Boeing PT-17 which was giving experience flights for paying passengers and a Boeing B-29 which was taxiing to take off.

The sequence that led to the tragedy began about five minutes into the performance, when the air boss, responsible for directing the choreography of the display, gave a series of rapid instructions.

First, he addressed the Flying Fortress leading the five bombers.

Air boss: B-17, after this pass, right 90 left 270.

Flying Fortress: Raiders, right dog bone.

I’m reliably informed that “right dog bone” is a repositioning manoeuvre involving a right 90° turn followed by a left 270° turn. In other words, exactly as the air boss had asked for, just using different terminology.

Then the air boss gave the fighter group three instructions back to back.

Air boss: Fighters, you can walk your way up to the B-17, I’m going to break y’all out after this, um—

Air boss: You’re going to end up breaking left.

Air boss: So, you’re going to follow the bombers to the right 90 out and then you’re going to roll back in left and be on the 500-ft line if y’all want to set up for an echelon for a break so y’all can get in trail.

Let me be the first to admit that I struggled to understand this, but on the ground, sitting at a desk, I worked out that he meant for the fighters to follow the bombers through a right turn, then pass them and break left, positioning themselves on the 500-foot show line in an echelon formation. It took me a minute, maybe two.

That is a lot of processing needed for a fighter pilot leading a high-speed pass.

Fighter group lead pilot: OK, uh, say again for the fighters, that was not clear.

Air boss: Fighters go echelon…uh, right, go echelon right.

Fighter group lead pilot: OK, fighters, echelon right

Key here is that the air boss did not repeat the instruction to be on the 500-foot line.

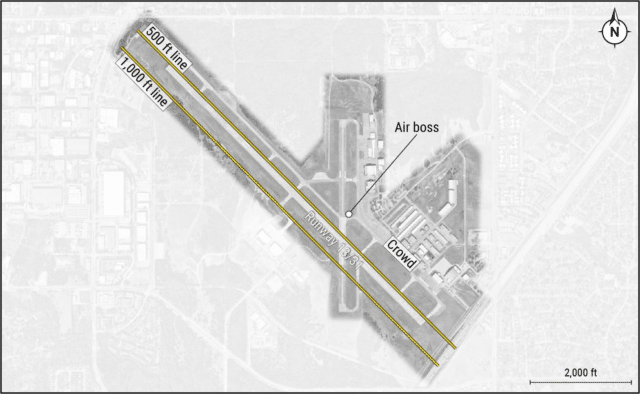

Air shows operate with carefully defined show lines – imaginary lines on the ground that define where aircraft can safely manoeuvre. The show lines at Dallas Executive Airport were set at 500 feet and 1,000 feet from the crowd line. These lines help maintain separation between aircraft and ensure safe distances from spectators.

The air boss continued to direct the aircraft.

Air boss: Okay, B-24 [the Consolidated B-24 in bomber position 2], if you could give me a couple of mi—, uh, inches and close the gap, I’d appreciate it. B-17, let’s keep the turn a little flat for me.

Flying Fortress: Roger.

Air boss: When you come back through, you’re coming through on the 1,000-ft line.

This is clearly meant for the B-17, as the air boss thinks the fighters know they should be on the 500-foot line. But this may have reinforced the idea that the fighters were to be on the 1,000-foot line.

Air boss: American fighters should be in a right turn. You’re going to follow the bombers out on a right 90 turn, and then I’m going to roll you back in front of them.

The fighters turned right, following the bombers who were also turning right. They held their altitudes between 1,000 and 1,200 feet above ground level. Next, the fighters will pass the bombers and cut in front of them, lining up on the 500-foot line. Again, this is never specified.

Air Boss There ya go, B-17. Yup. Gentle flat roll it around 1,000-ft line.

Flying Fortress: 1,000-ft line for Raiders.

Air Boss: Fighters, roll it back to the left. Lead fighter, roll it back to the left, and y’all get in trail.

Fighter group lead pilot: OK, fighters in trail.

Air boss: Yeah, and Gunfighter, look out your left side and find the B-17.

Fighter group lead pilot: We see the B-17.

The pilots don’t just have to focus on their position in the formation they need to maintain a visual reference of all other aircraft. This “see and avoid” strategy is critical to keep the two groups apart. The air boss is relying on the pilots to keep separation visually.

So, the P-51D Mustang confirmed that he had the Flying Fortress in flight.

The pilot of the second fighter said that he remembered the air boss giving a long stream of instructions, but he was focused on keeping the right distance from the lead aircraft. He looked over to be sure he had enough separation from the Flying Fortress and then focused back on the fighter lead.

Air boss: Yeah, there you go. Roll it back to the left. I want you to get in front of the bombers. I want you to come through on the outside edge of the runway.

The fighter formation entered the left 270° turn as they passed the bomber in the third position. The Flying Fortress was making slightly smaller, tighter turns than the other bombers to maintain its position as the lead aircraft.

Air boss: Nice job, fighters, you’re coming through first. That will work out. B-17 and all the bombers on the 1,000-ft line.

Air boss: B-17, you got the fighters in front of you off your left?

[unintelligible transmission]

Air boss: Nice job, fighters, come on through.

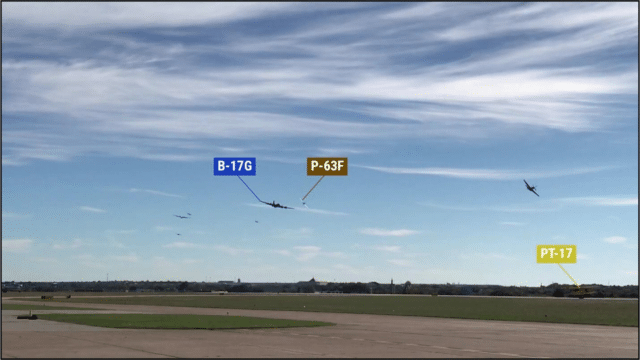

At this point, the P-51D Mustang, the lead fighter, had passed the Flying Fortress. The second fighter was passing the bomber and the Kingcobra was still behind.

The air boss intended for the faster fighter formation to pass the slower bombers on their left side and then cross in front of them to get to the 500-foot show line. The bombers would continue along the 1,000-foot show line.

However, the fighter lead pilot believed they had been directed to the 1,000-foot show line, and had not taken in the reference to the 500-foot line that the air boss had mentioned in his initial instructions. The Mustang pilot in the number two position later said that he’d also believed they were to be on the 1,000-foot show line. They banked left towards that show line as they passed the bombers.

The Kingcobra, the third aircraft in the fighter formation, initially followed the tight left turn of the number two fighter. But, possibly expecting to fly to the 500-foot line, he straightened out slightly, so that he was no longer closely following the track of the other two.

The first two aircraft had visually confirmed that they had passed the bombers but the Kingcobra, in the trailing position, had not yet passed the lead aircraft of the bomber group, the Flying Fortress.

The Kingcobra, in a descending left-banked turn, still slightly behind the Flying Fortress and at almost the same altitude, approached the Flying Fortress from above and behind.

The pilot’s view was obscured by the cockpit canopy. He clearly did not realise that he had not passed the bombers or, more importantly, that he was no longer in formation with the Mustangs. They may have been aligning to the wrong show line but they were visually clear of all other aircraft. The Kingcobra was not.

The Flying Fortress was partway through the “right dog bone”, having turned right 90° and now entering the left 270° turn. At the same time, it was climbing to maintain 800-1,000 feet above ground level.

A video from the crowd shows the Kingcobra, still in that left turn, striking the Flying Fortress near the trailing edge of the left wing. The Kingcobra broke apart in the air. The Flying Fortress’s broken wing caught fire as it fell and the aircraft exploded on impact. The wreckage of both planes was scattered in the grass south of runway 31. None of the crew members of either aircraft survived.

It had been less than two minutes since the air boss had given that first confusing instruction to the fighters; a minute and 35 seconds since the lead fighter had asked for clarification. During that time, there was no further reference to the 500-foot line, only mentions of the 1,000-ft line meant for (but not always attributed to) the bombers.

The NTSB have released a excellent animation of the aircraft over the airfield synched to the air boss transmissions. I highly recommend watching it to see how quickly this all came together.

The findings from the NTSB investigation showed that this tragedy stemmed from three key factors:

- There was no pre-briefed plan. The air boss was directing the performance in real-time, issuing a rapid series of instructions which created confusion about positioning.

-

The “see and avoid” strategy was inadequate for this complex performance. All of the pilots were juggling multiple tasks: maintaining formation, following instructions, and trying to keep visual contact with multiple aircraft.

-

The lack of standardised communications made for a heavier mental workload processing the real-time instructions.

From the final report:

3.2 Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the accident was the air boss’s and air show event organizer’s lack of an adequate, prebriefed aircraft separation plan for the air show performance, relying instead on the air boss’s real-time deconfliction directives and the see-and-avoid strategy for collision avoidance, which allowed for the loss of separation between the Boeing B-17G and the Bell P-63F airplanes.

Also causal was the diminished ability of the accident pilots to see and avoid the other aircraft due to flight path geometry, out-the-window view obscuration by aircraft structures, attention demands associated with the air show performance, and the inherent limitations of human performance that can make it difficult to see another aircraft.

Contributing to the accident were the lack of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) guidance for air bosses and air show event organizers on developing plans and performing risk assessments that ensure the separation of aircraft that are not part of an approved maneuvers package and the lack of FAA requirements and guidance for recurrent evaluations of air bosses and direct surveillance of their performance.

The air boss was directing the show as he always had. The pilots, all highly proficient, were following directions while maintaining their formation and keeping track of the other group.

The Flying Fortress crew were all seasoned airmen. The Kingcobra’s pilot had logged over 34,000 flight hours. This wasn’t about experience or skill.

The system itself is what failed. There was no pre-briefed plan, just real-time instructions. Everything hinged on a “see and avoid” strategy that asked pilots to do the impossible. Communication depended on the pilots quickly understanding the air boss’ intentions while doing all of the above.

The investigation exposed fundamental problems with how complex air show performances are managed.

This is a truth we keep learning in aviation: even the most experienced pilots and personnel can be let down by a flawed system. This isn’t about pointing fingers at individuals—it’s about recognising that complex operations need robust frameworks to support them. Air shows bring aviation to the public, and they deserve the same systematic approach to safety that we’ve developed in other areas of aviation.

Excellent analysis. I hadn’t realized that there were “air bosses” who would wing a show instead of giving cues for a plan worked out in advance; as a sometime stage manager, I can imagine the chaos if somebody tried to run a stage show that way. (Picture the Phantom’s chandelier winding up in someone’s lap….) I’m also surprised that there was a ?joyride? (“revenue flight”) going on at the same time; that meant there were really three kinds of radically different aircraft in the mix, not just two. AFAIK I haven’t been to airshows that offered joyrides; I’ve certainly never been on a joyride at a show with flying demos, and after this I doubt I will.

It would be interesting to know how much of this is specific to the “Commemorative” (formerly “Confederate”) Air Force, versus how often shows in general rely on live calls rather than planning all the display flights in advance; the end of the NTSB clip sounds like the FAA will be looking at all airshows to make sure they’re managed more carefully.

Totally avoidable. Two different aircraft, operating in close quarters needs a plan. The AirBoss needs to be called out

Given the fumbling we hear on audio, I’m not sure this particular airboss would be safe even with a plan. Unfortunately, I doubt the FAA is prepared to require airbosses to go through a lightweight version of ATC school and flunk out the ones who can’t hack it. I wouldn’t even try out — experience as a radio engineer taught me the limit of my real-time skills a long time ago — but it would be nice if there were standards of cope for this job.

Well said.

I was quite surprised when I learned that this air boss had in fact worked as an air traffic controller in 2007/2008, holding an “air traffic control tower operator certificate”. He was also FAA-certified as air boss.

The problem here is akin to one that Sylvia has blogged about in the past with pilots: that they’re getting into bad habits (e.g. flying unstabilized approaches, helicoptering with low cloud ceilings etc.). These habits reinforce themselves as long as nothing goes wrong. The NTSB report mentions that the Houston air boss ran his show in a similar manner, and he’s the Dallas air show’s father, so those bad habits kinda run in the family.

With pilots, this problem is nowadays getting adressed by recurrent training, checkrides, CRM, and SMS (safety management systems) that aim to identify and correct bad habits before something happens.

With air bosses, there is no such system. They are not subject to regular evaluation and training. Show pilot organisations like the Commemorative Airforce have a SMS, but it appeared to be underused.

Obviously not all air bosses need a support system like that, many air bosses put on safe, well-managed air shows. But then, not all pilots need check rides, either. But it’s worth it for those that do.

Good points — I hadn’t known that this airboss was once competent (although ATC are trained to keep planes safely separate, not to push them together for a spectacle). Do working controllers get evaluations as pilots do? I wouldn’t expect controllers at adjacent ~desks to notice anything short of a major breakdown, as I understand that ATC is generally overloaded; a supervisor might notice at an en-route center or larger tower, but that wouldn’t catch controllers at less-busy towers who fall into bad habits and/or lose their skills.

Good point, I should have highlighted that

Thanks for another interesting writeup. A sad story.

I’m VERY happy to hear the FAA and ICA were informed with suggestions for future airshows.

The Kingcobra sure is a good looking plane!

Gotta say, running an air show display without a pre-briefed plan is mind-boggling to me. Talk about setting yourself up to fail!