When Two 737s Collide

This Wednesday, the 11th of July, the Transport Safety Board of Canada have released an investigation report on the ground collision, fire and evacuation at Toronto Pearson International Airport in Ontario. It makes for an interesting anatomy of a ground-based emergency.

TSB Canada investigation report

Ground collision, fire, and evacuation

WestJet Airlines Ltd., Boeing 737-800, C-FDMB

and

Sunwing Airlines Inc., Boeing 737-800, C-FPRP

Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario

05 January 2018The TSB conducted a limited-scope, fact-gathering investigation into this occurrence to advance transportation safety through greater awareness of potential safety issues.

The collision happened on the 5th of January 2018. Both aircraft were Boeing 737-800.

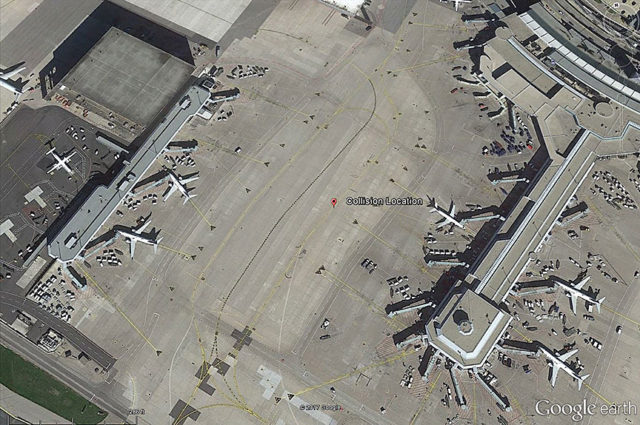

Westjet flight 2425 had just arrived from Cancún, Mexico, with 169 passengers and 6 crew members on board. They were holding near Terminal 3, across the back of Gate B13, waiting to be marshalled into Gate B12.

The Sunwing aircraft was parked at Gate B13 ready for towing to another location at the airport. There were no passengers or flight crew on board; a Sunwing maintenance technician was in the cockpit.

The Apron Management Unit is located in a tower at Terminal 1 and offer traffic advisory services to several apron and parking areas. The apron radio officers do not have a clear view of all of these areas and the visibility of the north-side apron of Pier B, where Gates B12 and B13 are located, is limited. To make up for this, there are video cameras mounted in strategic locations to provide live video feeds of the apron area. They also have ground radar (actually Airport Surface Detection Equipment or ASDE) which provides the apron radio officers with a real-time display of all the aircraft and vehicle traffic in the area.

There’s no way to know exactly what was displayed on the monitor at that moment but a review of the ground radar recording shows a clear radar target behind the Sunwing aircraft, in the direction that it was to be pushed.

That was the Westjet aircraft, which was stopped directly behind the Sunwing aircraft, perpendicular to it.

The tow vehicle connected to the nose of the Sunwing aircraft had two Swissport International ground staff on board. Swissport supplied ground operations for Sunwing, including towing and pushbacks.

The operator of the tow vehicle radio’d the Apron Management Unit (AMU) for permission to push back the Sunwing aircraft. The AMU north apron radio operator responded to ‘push back at your discretion’.

Normally, the call for an aircraft under tow would be the same as for an aircrat manoeuvring or taxiing. The operator should have identified the aircraft or tow vehicle, traffic information, confirmed the direction to push the aircraft and instructions to call back for taxi or tow instructions after the push. The traffic information would normally include the identification of aircraft in the area, give way instructions and the location of traffic conflicts. In layman’s terms, that would by something like, Hey! There’s a Boeing 737 directly behind you, don’t run into it.

The tow truck operator also had no one on the ground to help him see if he was clear. Usually, wing walkers are used to ensure the area are clear. Not, I hasten to add, the aerobatic type from airshows. These wing walkers are ground personnel who are positioned near the wing tips when aircraft are being pushed back or marshalled in, in order to watch that the area surrounding the aircraft is clear. However, Swissport procedure was to only use wing walkers for pushbacks when the aircraft has passengers on board. This one didn’t.

So, basically, every safety check failed. The tow truck operator began pushing the Sunwing back, straight into the right wing of the stopped WestJet aircraft in a sort of reverse-rear-ending.

Here’s the ATC audio as the collision happened:

The passengers on board the Westjet flight began standing up to try to see what was going on. The cabin crew were also not sure what had just happened and asked everyone to stay calm and remain seated.

The Westjet flight crew radio’d the AMU to let them know that they’d been in a collision. The AMU radio officer then contacted the tow vehicle operator to pull the Sunwing aircraft forward again, back towards the gate. As he made the call, a large fire ball erupted at the point of impact.

The Westjet flight crew immediately started working through the Boeing 737-800 evacuation quick reference checklist, including making a Mayday radio call to declare an emergency.

The AMU radio officer called Aircraft Rescue and Fire-Fighting (ARFF) services, and then air traffic control, updating them on the situation and the need for assistance. At the same time, the tow vehicle operator began pulling the Sunwing aircraft back towards the gate and away from the Westjet aircraft.

The Westjet wing’s fire extinguished as the Sunwing pulled forward but the Sunwing’s tail continued to burn. The auxiliary power unit (APU) at the back of the Sunwing was on fire.

The maintenance technician in the cockpit activated the auxiliary power unit (APU) emergency fuel shut-off valve and discharged the fire extinguisher, which is standard procedure. The APU compartment is considered at high risk for fire, so the priority is to shutdown the APU and cut off the air source. The engine nacelles and APU installations are designed to drain flammable fluids overboard; the goal is to isolate fires and control them so that they cannot spread to other parts of the airplane.

The technician then climbed out of the left cockpit window using the emergency rope. Although injured from the drop, the technician operated the APU fire extinguisher and fuel shut-off valve which was located in the aircraft wheel well for good measure.

The passengers on the WestJet aircraft panicked as they saw the flames out of the windows. The passenger seated at the left over-wing row opened the emergency exit and climbed onto the wing, other passengers followed, even though the engines were still running. There had not yet been any commands from the crew other than to stay seated.

The Boeing 737-800 has 8 emergency exits:

- two at the front of the cabin

- four over-wing exits

- two at the rear of the cabin

The over-wing exits don’t have emergency slides installed but instead use the aircraft flaps as slides once they have been lowered.

Two cabin crew members at the rear of the aircraft saw that the passengers were panicking and that an immediate evacuation was needed. They assessed the right rear exit but it was too close to the fire to be safe to use. One of them contacted the senior cabin crew member and the captain to state that there was a fire on the right wing and that they were evacuating. Twenty seconds after the fire started, they had the left rear exit open and the slide deployed.

The senior cabin crew member at the front of the aircraft was concered that opening the front doors would put the passengers at risk, because the engines were still operating. The front cabin crew members waited for a command from the captain.

The flight crew continued to work through the Quick Reference Checklist for evacuation, which included shutting down the engine and the APU and lowering the wing flaps so they could be used to slide down while evacuating. One item on the list was to pull the fire switches for the engine and the APU. As the fire had extinguished, the first officer didn’t think the item was relevant; however this meant that the emergency lights did not automatically activate and the area around the slides and overwing exits were not illuminated.

It was fifty seconds after the fire ball had appeared at their wing when the captain made the evacuation announcement over the public address system. The front cabin crew members checked the area for hazards and then opened the two front exits and deployed the slides. The first officer exited the aircraft to assist the passengers.

The cabin crew members instructed the passengers to leave all their carry-on baggage behind, but many pasengers insisted on grabbing their baggage and taking it with them, slowing down the evacuation.

Meanwhile, the passengers who had left the cabin through the left over-wing exits could not see where to go, as the over-wing escape route wasn’t illuminated. They re-entered the cabin, adding to the chaos.

The captain finally realized that the emergency lights were not illuminated and returned to the cockpit to find out why. He stepped through the Quick Reference Checklist again and saw that the APU was still operating. He shut it down and the emergency lights turned on.

The Boeing 737 is certified to meet the FAA regulations that an emergency evacuation at maximum capacity can be carried out within 90 seconds. The total time from the captain’s evacuation announcement to clearing the aircraft took two minutes and 23 seconds. Counting from the moment that the passenger opened the left over-wing exist, the evacuation took three minutes and nine seconds.

The Aircraft Rescue and Fire-Fighting services were on the scene in three minutes and twenty-two seconds. By now, the fire in the Sunwing’s tail and APU was smouldering. They extinguished the remnants of the fire.

There were three injuries: the technician who rappelled down from the Sunwings cockpit, a Westjet cabin crew member with minor hand injuries, and a fire fighter who was exposed to secondary spray which was mixed with fuel from the APU.

There was a social media storm about the fact that the passengers took their carry-on baggage with them, despite the cabin crew telling them to please leave everything behind for the evactuation. The TSB report points out that Westjet’s standard pre-flight safety briefing did not include the information that passengers should leave their personal belongings behind in the case of an evacuation. But to be fair, that briefing was four hours earlier. If those passengers weren’t going to listen to the cabin crew announcements at that time, a safety briefing which most people sleep through was very unlikely to make a difference.

Summary

In this accident, the pushback was conducted without the use of wing walkers, which is not in accordance with Swissport, Sunwing, and GTAA requirements. The investigation also determined that wing walkers were normally used by Swissport only when pushing back aircraft with passengers on board. In addition, the GTAA apron radio officer used phraseology that was not consistent with GTAA AMU procedures.

WestJet’s pre-flight safety briefings do not inform passengers to leave behind carry-on baggage in the event of an evacuation. During this occurrence, several passengers retrieved their carry-on baggage, despite the fact that FAs repeatedly provided specific instructions to the contrary. These passenger actions, in combination with the lack of emergency lighting, delayed the evacuation process.

You can read the full report on the TSB Canada site: Air Transportation Safety Investigation Report A18O0002

The total time from the captain’s evacuation announcement to clearing the aircraft took two minutes and 23 minutes.

Fixed, thanks!

Typo: “The total time from the captain’s evacuation announcement to clearing the aircraft took two minutes and 23 minutes.” probably should be “…two minutes and 23 seconds.”

Yes, it certainly should.

Thank you for sharing information timely. Again, the root cause of this case is a violation of the operational requirements. The question is how we supervise the execution of the operating procedures and the coordination of the procedures between companies so to delete the obvious difference, which may reduce the error of the third party executors.

ISTM that coordination isn’t the issue here; the full report that Sylvia links to says that Swissport violated its own published procedures by moving an airplane in the absence of wingwalkers. The first unanswered question is whether the fault lies with the crew chief of this operation (if there was a person in charge there — the report is unclear), or the manager who sent out an inadequate crew, or the (hypothetical) upper manager who told people on site to get jobs done without the proper crew. The report also shows that AMU failed to follow their own procedures; they were talking to a standing aircraft, not one moving several miles a minute, so they have no excuse for abbreviating the information they were supposed to pass.

Chip, I totally agree. The report suggests that proper procedures were followed.

Mechanics are not always trained in proper R/T procedures. Some airlines require that there ALWAYS be a cockpit crew member during any pull- or pushback. This is not always feasible, so others prefer to train tow truck drivers and get them a radio operator’s licence.

It would seem that even though the West Jet crew initiated emergency procedures, the evacuation was not really carried out as prescribed.

Passengers disobeying crew instructions and returning to retrieve baggage, potentially endangering the lives of others, should be charged with criminal behaviour (assuming they can be identified).

This also as a warning to others in (hopefully unnecessary) future cases.