Turning a Runway Overrun into a Crash (East Coast Jets flight 81)

Last week, I went through the details of the fatal runway overrun of East Coast Jets flight 81. This is one of those accidents where it seems easy to blame the pilots for not following procedure and then, when it went wrong, making bad decisions. I needed to split the posts in order to have the space to pull out the contributing factors and specifically the environmental factors which related to the final outcome. The actions leading up to the accident are a bit too convoluted to recap, so I’m going to ask you to read the first post rather than attempt to summarise it here.

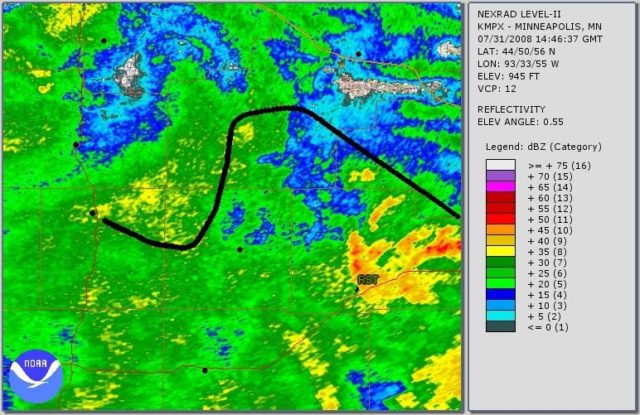

Note: The tail of the airplane is to the right and the wing section is on the left.

Fatigue

In the comments, Rudy brought up mild hypoxia as an option. This is an interesting comment because there are some telltale signs that would point to this or fatigue. Of course, if the pilots had not had sufficient rest in the days proceeding the accident, I would have mentioned it. I should add now that there were also no pressurisation issues or environmental issues in the cockpit; the contributing factors all started long before they got up for work that day.

That was at 05:00 that morning and the accident happened at 09:45, just a few hours later, so it was hardly a stressful day. Neither had flown in the days proceeding the accident. The flight itself was not long or particularly complicated and it was only the second flight of the day. There was no obvious reason to believe that they might be suffering from fatigue.

But fatigue is an insidious thing and one aspect of this case is how it can affect performance in circumstances which appear to be within normal limits.

The first officer had less sleep than he should; the early start meant that he only had six hours sleep that morning, instead of his normal rest period of nine and a half hours. But more importantly, he had stayed up late the nights before and then got up at his normal time, accruing a bit of sleep debt. The first officer suffered from insomnia which could make it difficult to fall asleep.

Here’s the problem: the FAA doesn’t really give any useful guidance when it comes to pilots and sleeping pills. This means that if you suffer from insomnia, whether through anxiety (the first officer often could not sleep the night before a flight, said his wife) or a chronic condition, then basic treatment is not easily available to you. Fatigue is well recognized as a priority issue in aviation; even minor fatigue has been shown to cause pilots making risky and impulsive decisions and to be late in changing plans, both of which affect the pilots ability to decide to abort a landing and try again.

The first officer took zolpidem, commonly known as Ambien, which the FAA allows but not within 24 hours of an assignment, which means that the first officer could never officially take this sleeping aid to help him before a flight. In fact, as a result of the FAA restrictions, he didn’t even dare ask for treatment for his insomnia; if he couldn’t sleep before a trip, he self-medicated by taking one of his fiancée’s prescription pills.

In the autopsy, they found that the medication was detected in his blood at a typical dose for sleep issues. This dose would case short-term sedation and impairment for about 4 to 5 hours; zolpidem doesn’t cause persistent performance reduction and there’s no ‘hangover’ – so this would not have affected his abilities that day. But his intermittent insomnia was clearly a type of sleeping disorder; one that would be considered trivial in most professions but is problematic for commercial pilots, for whom getting treatment is fraught with risks.

If he were a military pilot, then there would be no issue. In the US Navy and Airforce, pilots are allowed to perform flight duties just six hours after taking zolpidem. Military aviation has also approved another sleep-promoting medication, zaleplon, which has a shorter half-life than zolpidem, but again, the FAA offers no guidance for other medications or reasonable use of prescription sleep medications.

The Aerospace Medical Association makes the point clearly.

Facilitating quality sleep with the use of a well-tested, safe pharmacological compound is far better than having pilots return to duty when sleep deprived or having them return to duty following a sleep episode that has been induced with alcohol.

The NTSB agrees that allowing civil aviation pilots like the first officer the opportunity to use prescription sleep medications to treat occasional insomnia would improve their sleep quality and operational abilities. But at the moment, pilots cannot do so under medical supervision and, even they report their sleep disorder, physicians are given very little guidance when it comes to recommended treatment. This directly leads to situations like the first officer’s, where pilots are accumulating sleep-debt as a result of untreated insomnia and in desperation taking someone else’s prescription pills, knowing that they are risking their careers, in order to attempt to get enough sleep to be able to fulfil their duties in the cockpit. The medication the first officer took may be completely safe but the way he was forced to take it was clearly not. Struggling with insomnia, he eventually took medication which is known to be safe. But he’d already accrued the sleep debt and so the six hours sleep he got after taking the medication was not enough.

The captain also didn’t get to bed until midnight and only had about five hours sleep. This in itself could be enough to affect performance in a normal person who needs 8 hours sleep a night. However, when his fiancée described his normal sleeping patterns, it became clear that there was more to it.

On a normal night, the captain would sleep between 8.5 and 12 hours and then in the afternoon he would take a nap, usually 2.5 to 3 hours. His normal sleep pattern ranged between 11 and 15 hours of sleep every day. His college roommate and his father confirmed that this was normal for him; in their experience, the captain usually slept ten or more hours a night plus a daytime nap. Although his health was excellent, his sleep requirements point towards a sleep disorder. More importantly, “only” five hours sleep will have much more of an effect on a person who usually sleeps 11 to 15 hours than it will on a person who normally needs 8.

The result here is that someone who appears to have had a little less sleep than normal (five hours instead of eight) actually got a lot less sleep (five hours instead of eleven or worse, five hours instead of fifteen). More importantly, his sleep disorder was unacknowledged and untreated. This does a lot to explain why his decision making process shows the hallmarks of fatigue: quick to accept risky decisions and slow to reevaluate and change plans, as a fatigued person struggles to update strategies based on new information and is notoriously bad at risk assessment.

The captain’s performance during the landing, including his error of omission when he partially deployed lift dump, and his error of commission when he delayed the go-around, provide examples of how fatigue impairment can contribute to operational shortcomings when facing high workload demands, such as those associated with the landing rollout, and lead to serious errors and poor decision-making.

How Much Runway Do We Really Need?

I mistakenly described the runway friction as high because the runway was wet, where obviously I meant that the friction was low. For the avoidance of all doubt, the stopping distance required was greatly increased as a result of environmental factors, specifically the fact that they were landing on an ungrooved runway in the rain with a tailwind. None of this is fatal on its own but at no point did the flight crew discuss the landing situation and there was never any discussion at all as to what the effects of the wet runway and 8-knot tail wind would be. The crew appeared to simply thoughtlessly accept these limitations.

The runway was 5,500 feet long. The FAA recommends (but does not require) a safety margin of 15% when planning stopping distance. However, in this instance the simulator showed that, even if everything had gone perfectly, the aircraft would have stopped 100 to 300 feet beyond the end of the runway. A basic landing distance assessment would have shown them that the runway length was clearly not enough for them to manage with a 15% safety margin.

Instead, there was no consideration of the environmental factors and no thought put into what they should do if things went wrong. More importantly, the captain never realized that, even if he hadn’t screwed up, they were going to overrun.

But landing distance assessments were not a part of East Coast Jets standard operating procedures. There was no requirement that pilots should assess their landing distance based on the actual conditions upon their arrival. From the crew’s point of view, there was no expectation to consider the actual distance they required for landing on a wet, ungrooved runway in a tailwind.

So they didn’t.

In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king

The captain’s colleagues described the pilot as a serious and meticulous pilot and very supportive of first officers, which made it all the more mysterious that his Cockpit Resource Management skills, and those of his first officer, were so clearly lacking. The captain, as Pilot Flying, covered many of the first officer’s tasks as Pilot Monitoring. He did not maintain a sterile cockpit under 10,000 feet. In fact, he actually encouraged the first officer to engage in non-critical activity during final approach, specifically repeatedly phoning to find out about fuel and parking once at the airport, an issue that could easily have been resolved after they had landed.

The answer here is that competence and good CRM is relative. At an airline where professionalism is supported and rewarded, excellent pilots stand out. But at an airline where CRM and standard operating procedures are not taken seriously, the bar is a lot less high.

East Coast Jets used a company called Simcom for their pilot training. Simcom offered in-house training twice a year, including subjects such as CRM and emergency procedures. Simcom told the NTSB that they don’t have a formal curriculum or stated standards; they address the subject in the simulator and generally look for good communications between crew members.

Every pilot at East Coast Jets underwent Simcom training, including covering standard operating procedures (SOPs); however Simcom’s standard operating procedures were not included in the operator’s General Operations Manual. While this isn’t a requirement, it is recommended in order to ensure that there is clear reference to cockpit discipline and safe cockpit environments.

Not including the standard operating procedures in the General Operations Manual could imply that the emphasis on cockpit safety is only important for training and can be disregarded in the ‘real world’ once the training is finished. This was further underscored by the checklists in use, which were different from those used in training. Normally, if operators revise checklists, they provide a copy to Simcom to use during training, but East Coast Jets never did this. The end result was that pilots were given the impression that they needed to do one thing in training and another when actually flying.

Not surprisingly, the investigators also found that the pilots’ understanding of the standard operating procedures was generally lacking; company pilots weren’t able to cite or explain the procedures that they’d been trained in.

This is a common problem, where flight crew end up doing things one way to satisfy training requirements and then another way during operations. It could be that the official procedure is in some way not practical or effective. Or it might mean that the company culture and management are condoning the attitude that the standard procedures don’t matter.

The report highlights one key point: if company pilots are unable to list or explain the company’s SOPs, then the training has not been effective.

The NTSB concludes that, if, as a Part 135 operator, East Coast Jets had been required to develop SOPs and its pilots had been required to adhere to them, many of the deficiencies demonstrated by the pilots during the accident flight (for example, inadequate checklist discipline and failure to conduct an approach briefing) might have been corrected by the resultant stricter cockpit discipline. Therefore, the NTSB recommends that the FAA require 14 CFR Part 135 and 91 subpart K operators to establish, and ensure that their pilots adhere to, SOPs.

Working as a Team

However, none of this really explains how the Cockpit Resource Management (CRM) broke down so thoroughly in the approach and landing that day. And the answer here is the interesting one: it didn’t break down. It was never there in the first place.

At the heart of standard operating procedures is Cockpit Resource Management, putting procedures in place to reduce the effect of human error which focus on interpersonal communication, leadership and decision-making in the cockpit.

East Coast Jets had no course content to cover the subject and their operations manual doesn’t include CRM procedures. The training manual lists it as a subject but the manual does not include any course content. Simcom told the NTSB that they don’t have a formal curriculum or stated standards; they address the subject in the simulator and generally look for good communications between crew members.

The company often hired pilots locally from Ace Flight School. Newly hired pilots preferably had 1,500 hours and some multi-engine and jet airplane time. Staff said that new hires would begin as co-pilot on the Learjet, then move on to co-pilot on the Hawker and then hopefully to captain on the Learjet within about two years. An experienced Hawker captain told the investigators that flying with new pilots required a lot of talking and babysitting.

The East Coast Jets director of operations explained that initially, the first officers were told to just “sit there” and “not touch anything” and that they were considered “a detriment to the flight” but, with training from the captain, they would become a positive factor and, over time, they would be trusted to make landings on empty flight legs and then progress to landing flights carrying passengers.

I would like to point out that both the Learjet models owned by the operator and the Hawker Beechcraft 125-800A are rated for two-man operations; they are not designed for one of the flight crew to sit there and not touch anything.

The airline’s policy was to hire pilots with no prior professional charter jet experience and then pair them with experienced captains, who were expected to train them into being an asset. But the captains were not given any guidance as to how to train the new pilots and there was no training as to how to make the first officer a part of the team.

There’s no requirement for operators to educate their captains into how to train new officers to become an effective member of the flight crew. However, with no training support for captains and no CRM guidelines in the curriculum and no standards in the standard operating procedures, it’s hard to imagine how the captain is expected to know how to proceed. The flight crew effectively end up having to feel their way towards becoming a team, rather than the company giving them a road map.

It’s no surprise, in retrospect, that the captain did not rely on his first officer for support during the flight; company culture promoted the idea that he needed to fly the plane and then instruct his first officer as a secondary goal. The captain had 3,600 hours total flight time with 1,200 hours on type. The first officer had less than 1,500 hours of total flight time, with 300 on type. The relationship between them was not of a flight crew working together but that of an instructor and student, which is a very different type of cockpit management than a flight crew on a revenue flight. More importantly, the captain had no background as an instructor and no guidance from the operator on how he should be progressing the first officer from a student to a useful member of the flight crew. He was described as professional and meticulous and he may well have been an excellent pilot, but that doesn’t mean he was at all competent as an instructor or that he had any desire to instruct.

Although the captain was described as being very supportive of first officers, he did not make use of the other pilot as the Pilot Monitoring, instead delegating minor tasks. Instead of an approach briefing, he offered unorganised thoughts on the airfield.

The first officer was not given any useful tasks or information as to how he could support the captain during high workload phases of flight. So instead he found things to do, like trying to contact the FBO to ask about fuel and parking. Meanwhile, the captain unthinkingly performed many of the Pilot Monitoring duties, including responding on the radio. Effectively, the captain acted as if he were in a single-pilot operation, with the first officer only present as a trainee, expected to observe and learn rather than to support and monitor.

From a Board Member statement, where SIC stands for Second in Command, that is, the first officer.

I would be surprised and disappointed if two crew members of roughly comparable background and experience did not discuss that this landing was going to be pretty tight, and everything had to go exactly right in order to complete the landing successfully; I would not, however, be so surprised about the lack of such conversation in an instructor-student context, because the instructor, being by far the most seasoned, would probably plan to accomplish most the important steps alone in such a difficult maneuver. The absence of real engagement in the landing process by the SIC was also demonstrated by the fact that, less than three minutes before their touchdown, the SIC was on the radio to the FBO about matters that could easily have waited until after the landing.

The ultimate question, of course, is whether this type of instructor-student scenario should be permitted in revenue operations. Most passengers would not be pleased to learn that one of the two pilots of their two-pilot airplane is a “detriment to the flight.”

Conclusion

The flight crew made bad decisions from the start and were not able to manage their resources. They never evaluated their options or considered another approach, let alone what they would do if this approach needed to be broken off. Modern research into the importance of standard operating procedures, checklists and good CRM were completely dismissed by East Coast Jets as only necessary for the completion of training requirements. And so when things went wrong, there was no safety net at all for the flight crew.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the captain’s decision to attempt a go-around late in the landing roll with insufficient runway remaining. Contributing to the accident were (1) the pilots’ poor crew coordination and lack of cockpit discipline; (2) fatigue, which likely impaired both pilots’ performance; and (3) the failure of the Federal Aviation Administration to require crew resource management training and standard operating procedures for Part 135 operators.

The pieces of the puzzle finally fit together. The flight crew were not a team, the first officer was expected to sit there and not touch anything while the Captain single-handedly managed the Hawker. CRM at East Coast Jets was effectively non-existent, so the lack of the sterile cockpit and the lack of clear roles for the two pilots was business-as-usual, not a breakdown of communication. The captain, already fatigued, quickly lost control of the developing situation, as he attempted to manage all aspects of the two-crew aircraft. The two issues combined to cause him first to make an error (not deploying the lift-dump system on touch down) and then to require seven seconds to consider his error. The bad decision to go around was almost undoubtedly influenced by the fact that he had no idea how much time and runway had passed, as he was running way behind the plane. The Hawker could not have gone around at that late juncture but, even if there had been enough runway left, the inability to rely on his first officer for support meant that the aircraft was never configured to do so.

Such a tragic accident and worse, so easily avoidable. All it takes is for airline operators to accept the lessons that aviation investigations have taught us at the cost of other pilots’ lives, rather than to put their own pilots at risk.

Sylvia did a brilliant job here in her summary.

In the context of “FAR 135” operations, in many European countries commercial operators are required to adhere to standards very similar to those in the airlines.

Unlike under FAR 135, co-pilots on aircraft that require a two (wo)man crew must be trained and have a type rating in their licence, issued by the respective CAA. In some countries, there is not even a “Co-pilot” (part 2) rating: the pilot must conform to the same standards irrespective of captain or first officer. The conversion to command in those cases is entirely up to the company. In other words: there is no such thing as a first officer sitting on his/her hands whilst the captain operates the aircraft and tries to impart his or her superior knowledge and skills to the first officer.

I have once or maybe twice flown a Corvette single crew: the IAA had by mistake approved the aircraft (EI-BNY) for single-crew operations.

It was soon spotted with a sigh of relief: I had flown to Geneva to pick up a co-pilot (fully rated!) before heading for Paris Le Bourget to pick up the passengers. Even so, after this face-saving event the single-crew approval was hastily withdrawn. I could only fly with a non-type rated pilot in my capacity as TRI/TRE.

In defence of SimCom: In stutations as described, the training institute will usually ask the operator for their manuals and use the customer’s SOP’s during the sessions.

If no operations manuals nor SOP’s are provided, the training institution will fall back on their own books. Since they were not part of the operator’s library or SOP’s, crews were not using even them, that much seems obvious.

Fatigue and its consequences are comprehensively dealt with by Sylvia.

Sleep disorders are not usually admitted to because they can end a pilot’s career. And who will be the one to throw the first stone?

It’s so hard to know how to deal with those issues that hurt pilots: alcohol abuse, sleep disorders, depression, and I’m sure there’s many more. On the one hand, the passenger protection has to be paramount and pilots need to be at the top of their game. But how do we allow for recognition and treatment in an environment where admitting to the problems can mean losing everything. I find it heartbreaking.

Being a bloke with chronic sleep issues, I feel this accident was at least 50% the FAA’s fault.

I’m a software developer, so my clarity of mind has a significant impact on the rate and quality of my work.

When I’ve had sleep, I can juggle 6 or 7 issues with ease. When I’ve had my bad levels of sleep, I struggle to barely manage one or two. There’s even been times when I’ve had a hard time communicating what I’m working on to a colleague. I can’t imagine trying to manage the real-time workload I see my pilot friends experience.

Fortunately, I can come in at 10am and work until 7pm, so my problems are minimized. I’ve been in employment where the attitude was similar to the FAA’s where they tried to pretend it didn’t exist. It didn’t go so well.

So yes, I feel this is a direct result of the FAA’s “thou shalt not be imperfect” attitude.

I particularly noticed the difference between the attitudes of the US Navy / Air Force vs the FAA; it’s quite clear that this needed better clarification and the FAA need to avoid a blanket ‘treatment is bad’ response.

I am struck by “Not including the standard operating procedures in the General Operations Manual could imply that the emphasis on cockpit safety is only important for training and can be disregarded in the ‘real world’ once the training is finished.” It sounds like a report I heard of the opening lecture on a B-school course on Ethics and Business: “This is a course about Ethics and Business. That’s enough about ethics.”

I understand that the theory behind Part 135 was to provide air service in places that weren’t commercially viable for Part 91. The problem is that the existence of any regulation suggests a degree of safety that wasn’t present here — and was probably present only voluntarily in other Part 135 carriers. (This makes an interesting contrast with Rudy’s description of rules for the equivalent operations in Europe.) The idea that passenger flights are a place to conduct instruction is appalling; teaching flying is radically different from flying. (Now I’m thinking about the many connecting hops I’ve been on, usually on a carrier that was presented as part of a full-scale airline but was found in the fine print to be a separate corporation, and wondering how much the Part 91 carrier supervised the organization showing part of its name (e.g., American Eagle for American, Midwest Connection(?) for Midwest Express) — especially when one small-operations corporation was operating under multiple labels.)

Was East coast permitted to continue operating, given their pathological culture? I don’t know whether the FAA would be allowed to decertify the carrier entirely and require greater scrutiny of any other operation they became involved in, but ISTM that there are times when a broken culture can’t be fixed.

Note that the East Coast Jets culture was not breaking regulations so there wouldn’t be any clear grounds to stop them operating (but a lot of good reason to focus on them and their systems and discuss what is actually expected, which I would like to think has happened). I think this case is one of a few that made it clear that better focus on the ‘little guys’ is needed, while avoiding an environment where there is so much red tape that it becomes impossible to operate a small aviation business.

Another excellent analysis. Thanks so much.

I just spotted a post on an aviation website thats worth a look, seems there are similar issues at play.

Incident: Arabia A320 at Sharjah on Sep 18th 2018, intersection line up departed in wrong direction (AVH)

Thank you for that; I’ve added it to my list of things to read.

Gene, no doubt you realise that sleep deprivation when sitting behind a computer may influence your work, maybe even the quality. But in the cockpit of an aircraft the outcome can, and sometimes unfortunately is, lethal.

Airlines, especially small ones, have neither the resources nor the financial arm to deal with this problem. The crew are largely accountable for making certain that they are in compliance with rules concerning being fit for duty and are often under a lot of pressure to comply. Once, in the early ‘eighties, I returned from a charter flight with the Corvette jet – it was owned by GPA / Air Tara but managed by a small operator. This company also operated a commuter route with a Metroliner. It was at point of departure, passengers boarding, but the crew had failed to report for duty. In those days we did not have mobile ‘phones yet. So my first officer and I were told to do this flight – in a totally different aircraft. At the destination the seats would be removed for a night cargo flight, a few hours later. This was a single-crew operation, the F/O lived nearby and went home. I refused to do this as it would have brought me totally out of my duty hours. I was instead assigned another cargo flight, a more convenient one with a Shorts Skyvan. In the meantime, the captain of the Metroliner had been located and flew himself to the other airport in a Piper Aztec to take over the night cargo flight, and later do the early morning passenger flight back (with the same co-pilot who had had a good night’s sleep). When I returned with the Skyvan, I took the Aztec and flew back to base.

This is not to show how “good” I was, but to illustrate how the pressures can be on both operators and crews of smaller companies (Airports not mentioned, the company no longer exists)

In Europe, authorities have taken steps to regulate a lot of this. Even small operators must conform to training- and operational standards that still do not seem to apply to FAR135 operators in the USA. Or, if they do, the number of American operators allow some to slip “under the FAA radar”. Moreover, European operators (still) do not have the route structure that may require long positioning flights. A crew rest facility at another airport from where this crew will depart may in theory conform to legal requirements, but the sequence of spending hours in an airplane cabin, followed by a period in a crew rest facility may in reality be totally inadequate to ensure that the crew will be really fit. All may be fine until something occurs that puts extra pressure on the crew, like adverse weather. Suddenly, the routine is broken and they make decisions that are totally illogical. To allow passenger-carrying operations with a sophisticated bizjet in what in effect is a training flight, masquerading as a two (wo)man crew is fortunately not allowed in many, if not most, West-European jurisdictions. Especially not if the captain is not even approved by the authorities as an instructor-pilot.

To give an example how far the differences can be:

Now already probably more than 20 years ago, a KLM B737 made history when they were sent to Billund in Denmark for “base training”.

The newspapers zoomed in on the fact that all were women, instructor as well as trainees.

What many missed was that there was NO captain on board (!! yes, you read that right !!).

The instructor was a first officer. She possessed the skills, experience and qualifications to be an instructor on the 737 but she did not yet have the seniority in the airline to be a captain. Since the Dutch only know one type rating, she was totally, legally qualified to operate as an instructor. Under this system, a trainee may log a successful type rating exam flight as “command”.

I think that Chip got it nailed. He highlighted the origins of FAR135 and the potential consequences of a too “soft” supervision.

In the European aviation environment, there still is a stronger bond between operators, CAA and even crews, even if with the emergence of large entities like Ryanair this cohesion is less evident than it was in the past.

A totally fascinating analysis of the background factors. Quite scary.

I’m particularly impressed at the time and care that went into investigating this, rather than just dismissing it as flight crew acting badly, which was by far the easier conclusion.

Sylvia, to be fair to you: your readers know by now that you would not bother to publish it (over two weeks) if there had not been a story behind it.

Sylvia. Thank you for another thorough and dispassionate analysis of an aircraft accident. Apart from being really interesting, your blog is helpful in making pilots improve their craft, and hopefully useful to the public in taking the hysteria out of discussion of what can go wrong in the air. Thanks for the effort you put into ‘Fear of landing’.

I’m intrigued by the comparison that Rudy brought up between the FAA and European regulations for these sorts of operators. It makes me wonder about the quote by the NATCA ZFW FacRep in the ATC Heroes article, “…help maintain our portion of the safest airspace in the world.” Is US airspace really the safest with the regulations as they are?