TNflygirl and the Beech Debonair

On the 7th of December 2023, a Beech 35-C33 Debonair crashed into terrain. The private pilot and the passenger, the pilot’s father, were both killed on impact.

The private flight departed Knoxville Downtown Island Airport for a 430-nautical-mile flight to Saline County Regional Airport in Arkansas to pick up some avionics equipment. It was a practical errand in the fast Beech Debonair, registered in the US as N5891J.

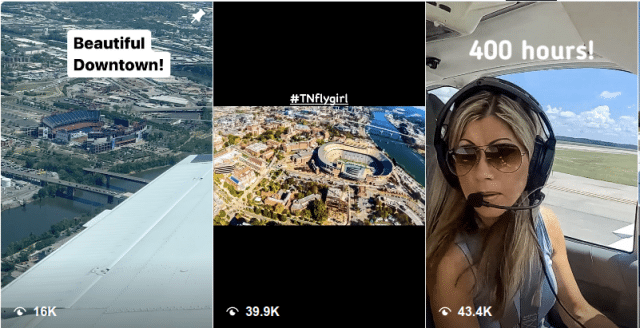

The pilot was a Tennessee entrepreneur who had been documenting her aviation journey since August 2021. Her YouTube channel, TNflygirl, followed her progress toward a Private Pilot’s Licence, sharing videos of her training sessions and cross-country trips. The YouTube channel has since been removed but viewers described her as refreshingly ordinary: a working woman and mother learning to fly. Her most popular video was probably “Pilot Training with my Dad,” which focused on her relationship with her father rather than technical content. Her father was not a pilot but was interested and engaged in her aviation adventures. The videos were polished with multiple camera angles and an upbeat presentation. They did not show evidence that she was distracted by the filming while flying.

In June 2022, she purchased a 1965 Beech35-C33 Debonair. The Debonair is considered a high-performance complex aircraft because the pilot must manage the retractable landing gear, the flaps and the constant-speed propeller system. One Debonair pilot described the aircraft as a Bonanza with a straight tail. “The Debonair is just as slippery and ‘go fast’ as the Bonanza, it picks up speed readily. You have to be thinking ahead of the plane at all times.”

The jump transition from a student pilot to the owner of a complex single-engine aircraft gave the channel a “level-up” storyline. What had been a training diary became a story of escalation: a newly certificated pilot stepping into ownership of a complex aircraft. The subscriber count rose to over 16,000.

Some of those videos, however, suggested gaps in her technical understanding. A PPRuNe thread has a discussion on how the videos show a lack of proficiency with the manual trim of the Debonair, which requires the pilot to manage the pitch trim in coordination with the Century 2000 autopilot.

One commenter explains: “On the control yoke there are no trim buttons, only an Autopilot disconnect switch. The Autopilot only lights a light when it wants a Trim change, but the Pilot must implement the change manually with the Trim Wheel. Sadly, the pilot does not seem to have grasped this.” In at least one now‑removed video where she tested the repaired autopilot, commenters later noted that the trim light was flashing continuously while she flew on autopilot and that she did not appear to respond appropriately to that indication, which they interpreted as poor understanding of how to manage trim with that system.

It is important to note that much of this analysis emerged after the accident. The available footage had been edited for presentation and was removed shortly after the crash. The remaining segments included in videos by other YouTubers were selectively chosen to show her issues. They may not represent her full operational competence.

That said, concerns about her handling of the complex aircraft were echoed by the General Manager of the Knoxville Flight Training Academy, where the pilot had trained until recently. On the morning of the flight, the General Manager spoke to the pilot and her father. The pilot told him that they were flying to Little Rock for a new avionics upgrade.

We talked for some time about her instrument rating training progress which had not been meeting necessary proficiency levels. I, along with my Asst Mgr. had given her an IFR phase check several weeks prior which did not go well on almost all aspects of aircraft control, situational awareness, and risk management. In particular I advised her that she was obviously way behind the Debonaire and that we thought she had purchased more aircraft than she was ready for.

He said that her new CFII was not from the academy but he had promised her that the school would be happy to assist her any way possible to get on track. He left the lobby and went on with his day.

Soon after, the flight departed Knoxville and climbed away normally. She levelled off at 2,500 feet above mean sea level for about twelve minutes, then resumed the climb to 6,500 feet.

According to ADSB data, shortly before levelling off at 6,500 feet, the aircraft’s groundspeed dropped to 80 knots. Once level at 6,500 feet, the Debonair accelerated to 130 knots and maintained that speed for the next ten minutes.

The flight was handed over to the next frequency, to Memphis Air Route Traffic Control Center. During the frequency change, the aircraft descended to 6,000 feet and climbed back to 6,500 feet.

The new controller advised the nearest altimeter setting and asked the pilot to confirm the aircraft altitude. The pilot acknowledged and confirmed 6,500 feet.

However, over the next 25 minutes the flight continued this pattern of climbs and descents. The Debonair descended, gaining airspeed up to 160 knots, then climbed back to 6,500 feet, slowing to 100 knots. Their altitude fluctuated by 1,000 to 1,500 feet at a time. Descent rates reached 1,200 feet per minute, while climb rates were closer to 500 feet per minute. Soon, the aircraft was no longer maintaining a steady altitude at all; each climb was immediately followed by another descent.

The Debonair entered a descent to 5,300 feet and then climbed to 7,000 feet before descending again.

The controller asked the pilot to confirm their destination, explaining that the aircraft was “well left” of its course. The pilot responded that she was correcting. A small heading adjustment followed, but the aircraft remained significantly left of course.

The oscillations continued over the next twenty minutes. The aircraft seemed to level briefly at 4,500 feet, slowing from 160 knots to 140 knots before initiating another climb. As it climbed above 6,000 feet, the airspeed continued to fall.

The next call, instructing the pilot to change frequency, did not get a response. The controller called again. No reply.

Two minutes later, a garbled transmission came from the pilot. “…this is Debonair [unintelligible] emergency…”

The aircraft entered a left turn and began descending at 2,000 feet per minute.

A minute later, a male voice was heard on the frequency, broadcasting, “help us.” The aircraft continued descending, reaching an airspeed of 230 knots and a descent rate of over 10,000 feet per minute. Radar contact was lost.

A woman on the ground heard the engine and looked up in time to see the Debonair fly directly overhead at high speed before plowing through the trees and crashing into the ground.

The NTSB spoke to one of her recent instructors, who had since left to work for an airline. He began instructing her in instrument flying after she had purchased the Debonair. He said that she was a super nice lady with a passion for aviation. But a previous instructor had told him that it took her over 180 hours to get her private pilot’s licence. According to what he’d been told, she’d initially purchased a Piper Cherokee, with a fixed landing gear and fixed-pitch propeller. Then, apparently, she had a hard landing on the Cherokee and damaged the nose gear, which was when she bought the Debonair.

In his words, the Debonair was “a lot of plane” for a novice and too much plane for her, or at least, too much plane to start with. He said that she needed a chance to gain more knowledge and experience before jumping into a complex high-performance aircraft.

The instructor confirmed that the pilot had struggled with the interaction between the autopilot and the manual trim. If the aircraft is “in trim” then it will fly straight and level in the current configuration. If it is “out of trim” then it will be pitched nose-up or nose-down and physical force on the controls is necessary to maintain level flight.

The final report described how it worked in the Debonair:

The airplane was equipped with a Century 2000 autopilot. This model was a prompting autopilot, meaning automatic control of the elevator trim (auto trim) was not available on this system. When the autopilot displayed a flashing TRIM UP or TRIM DOWN on the annunciator, the pilot would need to manually move the trim control of the airplane in the direction indicated on the autopilot.

When the autopilot determined that the trim condition was satisfied, the trim lamp on the annunciator would extinguish and the pilot could then stop trim action. There were 2 degrees of trim prompting: for a small trim error, the trim prompt will flash approximately once each second. A large trim error will cause the prompt to flash approximately 3 times per second. A large error not corrected for a period of approximately 2 minutes would sound an alert for 5 seconds. The alert would repeat every 2 minutes until the error was corrected.

In practice, this meant the autopilot did not trim the aeroplane for her but instructed the pilot to do so. The instructor said that when the annunciator flashed TRIM UP or TRIM DOWN, she would reach for the manual trim control. But sometimes she visualised it incorrectly, trimming in the wrong direction. “She would press the Down or Up button repeatedly. I would just tell her to gently press and hold the button down.” The autopilot would blink faster and faster to flag that she was trimming the wrong way. He said that she could get flustered by this and disconnect the autopilot, flying manually. That left her hand-flying an aircraft that was out of trim, increasing her workload.

From the docket:

She could fly the airplane. It was decent, but she needed help consistently. If an experienced instructor or pilot were not there in the right seat, she would likely not do to well between the radios, communication and managing the aircraft; I imagine she would get behind or lose situational awareness quickly. She just needed more training and confidence.

The General Manager from her previous flight school said much the same in his NTSB interview.

She had poor situational awareness. She rarely knew where she was in relation to her navigation. It was a complex high performance airplane with a technical avionics package, with which she was not truly familiar. I talked to our instructors, and they all stated they were having difficulty with her instruction. “I was the last one to talk to her that day. I told her you should not be flying that airplane. You’re not in control of that airplane.” The airplane was just too much for her.

They recovered the wreckage from a crater five feet deep by eight feet wide. When investigators reconstructed the wreckage in a hangar, they found no evidence of pre-impact failure. However, much of the engine and peripherals could not be functionally tested because of the damage on impact.

Post-crash toxicological testing of her liver tissue detected prescription medications. Alprazolam, used for anxiety and panic disorders, can cause increased sedation and reduced concentration. Trazodone, prescribed for major depression and anxiety disorders, may slow thinking and impair motor skills. Buspirone, also used for anxiety, can cause dizziness. The FAA considers all three to be “Do Not Fly” medications.

Ondansetron, used to treat nausea, is disqualifying for FAA medical certification because of potential side effects. Propranolol, prescribed for high blood pressure, is evaluated on a case-by-case basis. There was also evidence of a nasal spray for allergies, which is not considered impairing.

Only the nasal spray corresponded to the medical information from her most recent aviation medical examination at the beginning of the year. At the time, she reported that she had no active medical conditions and that her only medication was an over-the-counter antihistamine used to treat seasonal allergies.

Overall, the pilot may have been experiencing impairing effects of medication use or an associated underlying condition at the time of the accident, and such effects may have diminished her ability to render effective control inputs. However, available medical and circumstantial evidence was insufficient to establish whether such effects contributed to the accident, particularly given the pilot’s demonstrated baseline proficiency in the high-performance airplane.

The pilot had 390 hours flight time, of which 200 hours were on the Debonair.

FAA regulation 14 CFR § 61.31 specifies that for any aircraft with a retractable landing gear, flaps and a controllable pitch propeller, you must receive flight training and be found proficient in the operation and systems of the aircraft. Additionally, any aircraft with an engine of more than 200 horsepower requires a high-performance endorsement.

The Beech C33 Debonair qualifies as both. To fly the aircraft as Pilot in Command, you must hold your private pilot certificate and both endorsements.

The pilot’s logbook was partially destroyed in the crash, including the section where her endorsements would be listed. There’s no information as to whether she held the endorsements needed to fly the plane she’d owned for a year and a half. Neither the report nor the docket show evidence of any follow-up on this point.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be:

The pilot’s failure to maintain airplane control, which resulted in pilot-induced oscillations and a subsequent loss of control and impact with terrain.

In the end, the pilot is responsible for the flight. But I can’t help but wonder about the context of this one.

Did a CFI give her the endorsements needed to be the pilot-in-command of the Debonair? Or had someone signed off on her solo flight to Arkansas? She was happy to tell the General Manager her plans, so she, at least, believed that she was legally able to fly the flight solo.

The NTSB report quotes her recent instructor and the General Manager of her previous flight school at some length. Both described her as struggling and not ready for a complex aircraft. The report, however, does not explore how she came to be operating that aircraft alone on a cross-country flight that they did not believe she was competent to fly.

Q: she was working on an instrument rating, but the report mentions instruction from a CFI; should this be CFII, or was the CFI working with her on learning to control a complex aircraft?

I’m not surprised that nobody tried harder to get her to step down to a more manageable plane. I’ve noted before that the libertarian attitude of much of the US pushes against people interfering with other people on a road to destruction — especially in certain parts of the country, and especially if the person has money. (If she could afford a Debonair, she probably either had or was making a lot more than any of the people who knew that she was way over her head.)

I also wonder about the drugs; is it possible she lied at her last physical about what she was taking? (I see no medical records among the many pieces in the linked docket.) Or were they started in response to her difficulties with the aircraft? (She may have seen a certified specialist for her physical and her regular doctor for drugs; absent an obvious cause, they wouldn’t have talked to each other.) I wonder whether any FBO has “Just say no to drugs!” posters, or something less antique and more effective.

We’ve already talked about the dangers of doing selfies while piloting.

It was CFII, that mistake is mine. Fixed above!

I’m not surprised that no one tried to talk her out of it; it’s her money and her plane, after all. But I would like to know if someone signed her off, actively giving her the message that she was safe to fly on her own (her father wasn’t a pilot). It just bothers me that this was seen as a non-issue, maybe because there’s nothing to be done anyway.

With the medication, yes, I think that that is exactly what they are putting forward; either she lied during her last medical or she started a regime during the year and ignored warnings not to operate heavy machinery etc. Her sister commented that she didn’t know, they didn’t talk about such things, so it may well have been connected to general stigma for mental health prescriptions.

This generally doesn’t apply to serious aviation youtubers, as they have fixed cameras installed that record the whole time, and they edit it down at their desk later.

The NTSB found 2 cameras in TNflygirl’s wreck. One camera was too damaged, but they were able to read the files off the other one, and determined that it hadn’t been recording on the accident flight. That means the youtubing played no direct part in the accident sequence, though it may have contributed to the pilot’s reluctance to downgrade her aircraft. I imagine it’s easier to take that step when the whole world doesn’t know about it.

Those are both fair points. The one picture from her feed does look like the camera is mounted; both her hands are down while the view is from above — but I wonder how long she was looking away from the controls (or what was ahead of her) during that shot. And I can certainly see her worrying about losing the followers she’d gained on stepping up if she stepped down; airplanes are not a place for egos.

One small correction- I don’t believe she was a mother.

Huh, I wonder where I got that from. Thanks for that, I’ve fixed it.

I’ve come to the conclusion that the autopilot issues are a red herring; after all, we have testimony that TNFlygirl would turn it off if it didn’t seem to be working.

From the graph in the report that details the last few minutes of her flight, it looks to me that she hand-flew to her doom. The weather was fine, with no clouds and 10 miles visibility, but she was unable to manage her airspeed, altitude, or heading. I believe she descended into overspeed, and then something finally broke on that long-abused aircraft.

https://youtu.be/R1W1ml-uRT0 is a commentary on one of her videos posted 1 year before the crash that highlights issues nobody with a OPL should have: would you fly west if your journey is to travel 40 miles to an airport almost directly due east? The mismanagement of speed, altitude and heading is all there. Maybe the autopilot in her old Piper helped her more than the AP in the Debonair did; in that case, the “upgrade” was the beginning of the end.

It’s stunning that she had all these videos to review her own performance, but seems not to have learned anything from it.

Eh, they found the undamaged trim-tab in a 5 degree down position, so it’s not like it would be a non-factor in, I guess, uncontrolled flight into terrain. I think why it isn’t a red-herring is that she was fooling with the AP altitude for some time and likely lost track of any sense of actual aircraft trim: the tab was at five degrees, but it’s possible she was rolling that trim wheel during the dive and only ended at five degrees, right?. With a degree of fluster and performance anxiety in front of her non-pilot father, a warning at the FBO, a tendency toward inattention to actual aircraft attitude while heads-down in the “technology” she was said to overfocus on, and a noted deficiency in situational awareness, I think the aircraft pitched down the instant the AP was turned off and for the many factors outlined in the report, she just didn’t react right to the sudden unusual attitude.

I’m not saying you’re wrong, of course, and something could have broken on that plane. But as I recall, the damage to the control wires was consistent with breaking from impact and I didn’t see anything listed about corrosion or failure of anything on the plane. But yeah, I think the instant the AP was shut off, she was suddenly in a desperate dive and may not even have noticed before things were unrecoverable. It’s a shame, for real, and I’m not sure this wasn’t an inevitability if she were to attain her IFR and get into conditions more challenging than the perfect weather she was in at the time of the accident.

It’s always possible that the report was worded incorrectly, but the way elevator trim tabs work is such that when the tab is down, the airflow over the tab makes the elevator move up. And up elevator makes the nose want to go up. See https://www.boldmethod.com/learn-to-fly/systems/4-types-of-trim-tabs-operation/ for an animated schematic of this.

So if I’m not mistaken, the aircraft was trimmed nose up when it crashed.

And yes, obviously that could’ve been effected during the dive, when it was too late.

The Piper TNFlygirl first flew has a trim crank on the roof. Apparently she did not transition well to the trim wheel under the dash.

The Tennessee Fly Gal had no business flying a complex airplane. She could not fly straight and level flight without the auto pilot. She could not navigate without GPS. Her flight instructors were not honest with her about her lack of flying skills, she did not know where she was and would fly in circles, where was the sectional chart? Even with the GPS and auto pilot she would get disoriented and did not know where she was.She needed to back to basics on how to trim the aircraft , navigation an d hand flying. She dependent on the auto pilot and that’s what killed her. If Her flight instructors had been honest with her and actually helped her she would not end up with the situation she got herself into.

Instructions