The Fenestron Factor: Cabri G2 Crash in Gruyéres

The Swiss Transportation Safety Investigation Board (STSB) has released the final report for the Cabri G2 light helicopter crash in Gruyères, Switzerland in 2022. I wrote about it at the time, but I’m repeating the information and the videos here for reference. The final report is only available in French, with no mention of it in the English and German sites. I have used machine translation to make sense of it, so any errors or poor explanations are entirely my fault. I would be very happy if a French speaker were to check the French report and confirm the details!

The incident took place at Gruyère Aérodrome on the 15th of June 2022. The nine-year-old Cabri G2, registration HB-ZDQ, was a two-seater helicopter powered by a reciprocating (piston) engine. A private pilot and passenger planned an outing in the Cabri G2 which was owned and operated by Swiss Helicopter AG.

The pilot had trained for his private license with Swiss Helicopter in 2018. His aeronautical training was exclusively on the Cabri G2. He’d flown over 100 hours in the Cabri G2 and had his most recent proficiency check flight three weeks before. However, he was missing some critical safety information, specifically service letter No. 12-001.

CABRI G2

SERVICE LETTER 12-001

Yaw control in approach

It is recommended to keep this letter with the Flight Manual.

It is recommended to instructors that they insist on following matter during training and that they check it periodically.

The Cabri G2 comprises a shrouded tail rotor, usually referred to as a “Fenestron” (a registered trade mark of Eurocopter) that was proven to provide excellent maneuverability in every flight condition, in every direction of flight up to 40 kt at least.

However, two recent incidents involving a loss of control in yaw, both with pilots with no previous flight experience in a Fenestron-equipped helicopter, lead Hélicoptères Guimbal to issue this Service Letter in order to point out some specific characteristics of such tail rotors. These characteristics are common to all helicopters equipped with a Fenestron, and are covered by several publications, including Eurocopter Service Letters N° 1673-67-04 (CW rotors) and 1692-67-04 (CCW rotors).

The service letter goes on to explain that the Cabri G2’s Fenestron tail rotor requires immediate and significant right pedal input to counteract the yaw movements, especially during low-speed manouevres. Additionally, it highlights that winds coming from the right rear quarter reduce the effectiveness of the Fenestron, which makes it more difficult for the pilot to maintain yaw control.

In the event of an unintentional left yaw, the pilot must immediately apply right rudder, that is, firmly apply pressure on the right rudder pedal. The key is to respond swiftly and with rather more right rudder than might be expected from pilots without experience with Fenestron-equipped helicopters.

However, when asked later, the pilot had never heard of the issue and was unaware of the need to quickly and, more importantly, firmly apply right rudder.

The pilot and his passenger arrived at the airport around 13:00 local time for the pleasure flight. The weather was clear. The Cabri G2 was in fine health, having been given a new engine and main transmission gearbox during its 100-hour inspection just a few weeks before. The pilot met with the airfield manager and organised 60 litres of fuel for the helicopter. Then he filled out a flight plan with their intended route to head to Jaunpass – Lenk – Col du Pillon – Aigle – Lausanne and then back to Gruyére. The flight plan referenced the current weather, specifically noting a westerly wind at 15 knots at 5,000 feet above mean sea level, with gusts up to 25 knots at higher altitudes.

The pair took off from Gruyère Aérodrome at 14:00. The pilot did not know that wind from the right rear quarter caused issues with the fenestron. At about 50 meters (165 feet) above the ground, the pilot turned left, planning to fly over the grass runway as the start of his routing. In the turn, the wind gusted over the right rear quarter of the helicopter, leading to exactly the condition highlighted in the service letter.

The Cabri G2 began to yaw to the left and then began to rotate. The pilot carefully pressed the right rudder pedal to counteract the yaw, but he did not know that he had to apply rather more right rudder to regain control. The helicopter continued rotating left. The pilot lowered the collective lever by 50%, which decreases the pitch angle of the main rotor blades and thus reduces the lift generated by the rotor. Reducing the lift and decreasing the torque effect helped to stabilize the helicopter. They continued straight for a few metres, very low above the ground, before the helicopter again yawed to the left. They crashed into a field east of the runway, breaking the skids off. The Emergency Locator Transmitter activated. The helicopter, still powered, briefly lifted off again. Then it crashed to the ground again and this time, it stayed there.

A unknown bystander who saw the helicopter starting to spin quickly captured it on video.

The entire flight lasted about sixty seconds.

The pilot was uninjured. He quickly cut the engine and stopped the main rotor before exiting the helicopter. The passenger reported significant back pain and was transported to hospital and held for forty-eight hours. When the police arrived on the scene, they declared it a miracle that the pair had survived at all.

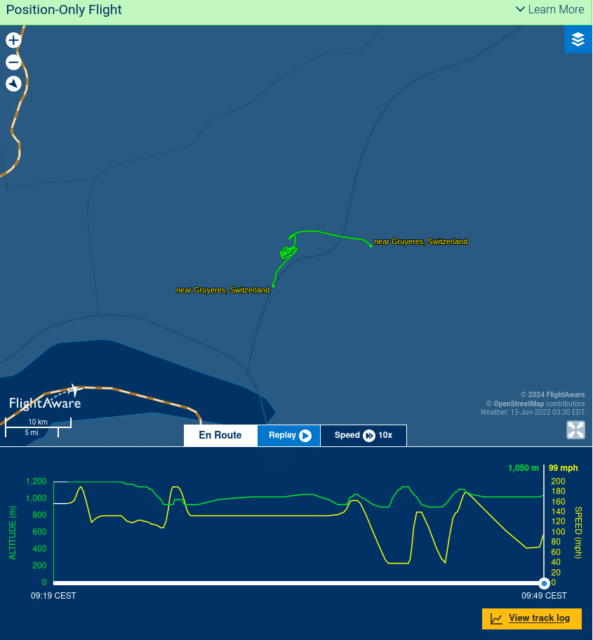

This seems to be the final flight taken by the aircraft, which shows on FlightAware as a series of squiggles.

The Cabri G2 is still listed on the Swiss registry but with a location of not in operation.

Cause

The accident was caused by a loss of yaw control at low speed and low height in the presence of gusting rear wind. The following factor contributed to the accident:

- Lack of knowledge of the characteristics of the fenestron tail rotor.

Swiss Helicopter stated that the contents of Service Letter No. 12-001 was covered as a part of the ground training; however, the pilot had no recollection of this. It is clear that the instructor did not revisited the issues with the fenestron as a part of the pilot’s proficiency check three weeks before the flight. The report concludes that there was a lack of awareness and understanding of the yaw control issues indicating a gap in the training and proficiency check process.

The final report in French is available on the STSB website. Again, if I missed or misunderstood any aspect of the report (my French is limited to Voilá! and pain au chocolat) please let me know in the comments.

I Learned to fly in Robinson R22 and R44 helicopters, and still fly them and other types. I also have around 1,500 or so hrs of instruction in the G2.

Like all helicopters, loss of tail rotor effectiveness (LTE) is absolutely a genuine concern and is a hazard to be aware of. However, avoidance and recovery are both simple enough for first time students to grasp with very little practice.

Whilst hovering, you’ll need a fair bit of right pedal in this machine. Assuming the G2 takes off into wind, within a few seconds you’ll quickly find that the tail fin begins to become more and more efficient and the need for power pedal to oppose engine torque reduces quite quickly. Assuming again that you maintain some airspeed (15 kts or so at the minimum, well below best rate of climb speed (50 kts) you’ll never have a problem of insufficient pedal.

If however, you turn downwind at very low airspeed, yank the collective up and don’t apply more right pedal, you’d likely see this kind of result.

Again, to clarify, LTE is real, and is a result of aerodynamics, but this was most likely a chain of pilot mishandling by not ‘flying the numbers’, mishandling, lack of anticipation of the requirement for more right pedal and more mishandling to recover.

TLDR: More right pedal would have fixed this.

The TLDR made me laugh.

The service letter quoted by Sylvia says:

This means a G2 pilot always has the pedals available to counteract yaw, as long as the tail rotor is working.

The problem that the service letter points out is that a right crosswind counteracts the sideslip induced by the onset of yaw, potentially catching the pilot unawares.

There’s another issue mentioned in that service letter that may apply here:

I won’t pretend that I understand all of that, but 3800 ft is 1160m, which is close to the altitudes in the FlightAware track, and may be even higher on a warm summer’s day when the air is thinner.