Steve Fossett Disappearance

It was the 3rd of September in 2007 at around 09:30 local time in California when a Bellanca 8KCAB-180 (Super Decathlon) registration N240R disappeared in the ‘Nevada Triangle’.

The 63-year-old pilot was Steve Fossett, a famous aviator and sailor. He is still the holder of multiple world records, including the fastest east-to-west transcontinental record for non-supersonic fixed-wing aircraft, flying from Jacksonville, Florida to San Diego, California in 3½ hours. He was also the first solo pilot to achieve a nonstop (un-refuelled) flight around the world in an aircraft. He departed Kansas on the 28th of February 2005 and returned to his airfield on 3rd of March after sixty-seven hours of flight. This flight is still the record holder for fastest circumnaviation of the world, nonstop and non-refuelled, with an average speed of 550 km/h (340 mph) in the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer.

Fossett held an airline transport pilot certificate (ATPC) with more privileges and ratings than I can be bothered to list. Actually when I looked up his records, I was slightly surprised to see that he had a total of only 6,731 hours flight time. It’s not a trivial amount, by anyone’s count, but I presumed that someone working as a test pilot and record setter would have more, somehow.

Anyway, suffice it to say his paperwork was in order and his experience was good. However, he had only forty hours flight time in the aircraft that he was flying that day.

The Bellanca 8KCAB-180 ‘Super Decathlon’ is a single-engine high-wing fixed landing gear aircraft. The two-seater plane made from wood and fabric is popular for training and aerobatics. This specific Super Decathlon, registration N240R, was nearly 30 years old. It had passed its annual inspection in April 2007. Six weeks later, the Super Decathlon ran off the runway during its landing roll, crashing into a barbed wire fence. The propeller was replaced and the aircraft was returned to service on the 29th of June. At that time, it had 1,094.7 hours and the chief pilot said that the aircraft flew 10 to 12 hours after being returned to service.

The Super Decathlon was kept at the Flying M Ranch, a private strip located near Smith Valley, Nevada. The Flying M Club is at the centre of a million-acre estate and one of the most sought-after takeoff spots in the US; the club’s fans have included Buzz Aldrin, Morgan Freeman, Sylvester Stallone and John Denver. It’s known as a base for wealthy amateur pilots. The area is famous for the strong desert thermals which allow for gliders to circle for hours.

On the 1st of September, two days before the flight, the chief pilot and another pilot put the Super Decathlon through its paces, performing extensive aerobatic manoeuvres without incident.

Morning dawned on the 3rd of September with clear blue skies, a wonderful day to go flying. Fossett and the chief pilot had breakfast together and Fosset said that he wanted to fly the Super Decathlon that day. His wife described Fosset’s plan as a flight for pure pleasure, “a Sunday drive”.

The chief pilot went to the hangar to confirm that the Super Decathlon was full of fuel and ready for flight. Fossett arrived at quarter past eight and ran through his pre-flight checks.

After he finished, the chief pilot took a moment to review with him the starting procedures of the fuel-injected engine and asked Fosset where he was going that day. Fossett told him that he planned to head south to Highway 395, which runs north/south along the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada mountains. He did not wear a parachute and did not mention any intention to perform aerobatics. He took the front seat of the tandem two-seater aircraft.

The chief pilot expected Fossett to be gone for two hours or so and he got on with other things. Another ranch employee remembered looking up and seeing the aircraft flying around nine miles south of the airstrip. He immediately recognised the Super Decathlon, as it was used for spotting cattle which he rounded up on the ground. He saw it flying around 150-200 feet above the ground, heading south.

This was the last verified sighting of Fossett in the Super Decathlon.

Fossett’s personal pilot arrived at 11:00 to assist with parking the plane (I have to admit to a twinge of jealousy here – I would love someone to come and park my aircraft for me!) but Fossett still hadn’t returned. By 11:30, the chief pilot became concerned. The aircraft had an endurance of four to five hours and Fossett had only mentioned a short flight.

Within half an hour, he had organised an aerial search. The Super Decathlon had an Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) but no transmissions were picked up and there were no records of emergency radio transmissions.

Meanwhile, it was clear that the Super Decathlon could not possible still be flying.

Soon, an extensive search was underway, including the Civil Air Patrol, State and County authorities and friends of the pilot. Between them, they searched terrain across several counties and crossing the state line. The search involved 629 flights of 1,774 flying hours to cover 22,000 square miles (57,000 km²) of rugged terrain in difficult flying conditions. High winds caused the operations to be suspended at midday on day two and the winds continued to pose difficulties throughout the search.

A possible witness was found. A camper at East Lake reported that he’d seen an aircraft in the area which might have been the Super Decathlon. He was camped at an elevation of 9,400 feet, where the peaks in the area reached 12,000 feet. It was a little before 10:00 when he saw the aircraft flying from north to south, heading towards Yosemite. He pointed out the plane to the other people who they were camping with, as the aircraft was heading into the wind and it looked almost like it was standing still. He believed that the aircraft was at about 11,500 feet.

However, the searchers found no trace of missing aircraft and pilot and as the days went past, they knew the chances for his survival were dwindling.

Four days after the disappearance, high-resolution satellite imagery was made available on the Amazon Mechanical Turk website in hopes that the public could flag potential areas of interest for the searchers. Some 50,000 people took part in the crowd-sourced search, poring over 300,000 detailed photographs each covering 278 square feet (25 m²) of terrain.

However, the online search did not flag any areas of interest. The Civil Air Patrol was flooded with emails and phone calls from people convinced they had seen something, including many sightings of intact aircraft, which turned out to be search aircraft scouring the area. CAP’s Public Affairs representative said it was more of a hindrance than a help. She told Wired magazine at the time that, “The crowdsourcing thing added a level of complexity that we didn’t need, because 99.9999 percent of the people who were doing it didn’t have the faintest idea what they’re looking for.”

By the 12th of September, the searchers knew that Fossett was unlikely to still be alive. By the 17th, the Civil Air Patrol suspended their search flights, although National Guard and private search flights continued. By the 2nd of October, the search operation was called off. It had been the largest and most complex peacetime search for an individual in US history but it had failed.

Eight previously uncharted crash sites were reported over those weeks but, as they were hoping to rescue Fossett if he had survived the crash, the searchers took only enough time to verify that the wrecks could not be the Super Decathlon before moving on.

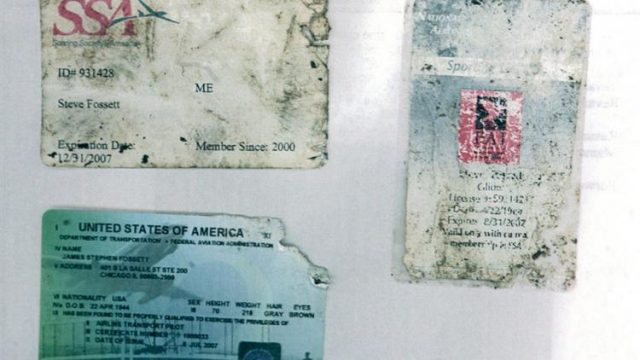

It was a year later almost to the day, when finally a breakthrough occurred. A hiker in the Sierra Nevada Mountains contacted the Madera County Sheriff’s Department to say that he’d found some personal effects, including an identification card and a pilot certificate, near Minaret Summit. Both documents belonged to Steve Fossett.

Travelling to the location described by the hiker, they discovered more effects: a pair of tennis shoes, credit cards, and Fossett’s drivers license along with skeletal fragments. About half a mile from there, they finally found the crash site. The peaks of that area rose to 13,000 feet and more. The location was about 30 miles south of the East Lake campsite where the campers had seen a plane flying against the wind. The Civil Air Patrol confirmed that they’d searched the area once by air, however they had seen nothing to make them aware that the aircraft was there.

Once there, they discovered a boulder at 10,000 feet with paint transfers on it from the belly of the aircraft and the left main wheel. Pieces of wreckage was scattered uphill among the charred plants and scorched earth. Looking uphill about two hundred feet from the boulder, they found the burnt remains of the steel tubing frame of the fuselage. The wings were broken, the fabric burned away.

The door was still attached to the doorframe with the emergency release handle still locked. The front seat, where Fossett had been sitting, was crushed to about 1/3 of its original dimensions. All of the instruments were destroyed, as was the Emergency Locator Transmittter.

The nearby pine trees needles had turned dark from fire. The battered engine lay another one hundred feet uphill from there with the propeller blades broken off.

Small bone fragments at the accident site were collected but it wasn’t possible to tell if they were human remains. The skeletal fragments found near the paperwork were confirmed by DNA to be the remains of Steve Fossett. The cause of death was given as multiple traumatic injuries.

Once they found the aircraft, they were able to isolate the radar tracks from that day in order to follow the route that the Super Decathlon took. It was a southbound track which had been spotted on radar from the start.

According to the radar returns, at 09:07 there was a target flying southbound, following the crest of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, about 35 miles south-southwest of the Flying M Ranch Airport. The track of the target followed Highway 395 and then disappeared at 09:27 about one mile northwest of the accident site.

When Fossett had disappeared, this radar track had been eliminated as the timestamp did not agree with the Flying M employee who said he’d observed the aircraft 9 miles to the south of the airstrip. He’d said that he’d seen the aircraft between 09:25-09:35 and remembered the time because he’d been on a phone call when he saw it. This siting meant that the target appearing on radar at 09:07 couldn’t possibly have been Fossett. As they desperately needed to reduce the search area, they dismissed this and many other radar returns as irrelevant.

The Flying M employee had seen and correctly identified the aircraft. But when investigators checked the telephone company’s time log, the phone conversation was shown to be an hour earlier and thus the correct time of this last confirmed sight of Fossett’s aircraft was an hour earlier at 08:25-08:35.

Initially, the radar track showed that the transponder of the target was reporting altitudes of 14,500-14,900 feet. After the first few minutes, no altitude information was received.

The wreckage of the aircraft showed that the Super Decathlon was at 10,000 feet and heading north at the time of impact. This means that the Super Decathlon had turned 180° after radar contact was lost.

The transponder altitude shows the pressure altitude, which means that it is unaffected by your setting the local pressure. ATC then adjust the reading for the local altimeter setting but, in the case of the radar return, that is the raw data as sent by the transponder. So to understand the actual altitude of the aircraft, we need to look at the weather that day.

Mammoth Yosemite Airport is about fifteen nautical miles from the crash site, at an elevation of 7,129 feet. On the day of the crash, the 3rd of September, the density altitude at the airport at 10:49 was 9,700 feet. That is to say, the difference between the pressure altitude at the airport was over 2,500 feet.

AOPA Pilot Safety and Technique Resources

Density altitude is pressure altitude corrected for nonstandard temperature. As temperature and altitude increase, air density decreases. In a sense, it’s the altitude at which the airplane “feels” its flying.

On a hot and humid day, the aircraft will accelerate more slowly down the runway, will need to move faster to attain the same lift, and will climb more slowly. The less dense the air, the less lift, the more lackluster the climb, and the longer the distance needed for takeoff and landing. Fewer air molecules in a given volume of air also result in reduced propeller efficiency and therefore reduced net thrust. All of these factors can lead to an accident if the poor performance has not been anticipated.

This means that the aircraft would have been slower to climb than expected. The Super Decathlon’s maximum rate of climb at a pressure altitude of 12,000 feet was 370 feet per minute. At 13,000 feet, its maximum rate of climb was 300 feet per minute.

That in itself would catch out an inexperienced pilot; however, Fossett knew the area and shouldn’t have been taken unawares, even with the increased density altitude that day.

A meteorologist did a simulation of the conditions that day based on the Advanced Research Weather Research and Forecasting numberical model. His simulations showed downdrafts in the accident area of 300 feet per minute and in one case, as high as 400 feet per minute. The meteorologist believes that these were underestimated, as the simulation didn’t fully take into account the steep terrain slopes.

Visual meteorological conditions existed in the accident area at the time of the accident. Mean winds at 10,000 feet were from 220 degrees at 15 to 20 knots; some gusts of 25 to 30 knots may have occurred. Moderate turbulence and downdrafts of at least 400 feet per minute probably occurred at the time and in the area of the accident. The magnitude of the downdrafts likely exceeded the climb capability of the airplane, which, at a density altitude of 13,000 feet, was about 300 feet per minute.

The Super Decathlon was unlikely to be able to keep altitude, let alone climb over the mountain range. However, the downdrafts wouldn’t have really come into their own until he came closer to the rising terrain. By the time that Fossett realised he was in trouble, it was too late.

Here’s the NTSB conclusion:

Examination of the accident site revealed that the airplane was on a northerly heading at impact, indicating that the pilot had executed a 180-degree turn after radar contact was lost. Ground scars and distribution of the heavily fragmented wreckage indicated that the airplane was traveling at a high speed when it impacted in a right wing low, near level pitch attitude. A postimpact fire consumed the fuselage, with the exception of its steel frame. The wings were fragmented into numerous pieces. The ELT was destroyed. Damage signatures on the propeller blades and the engine crankshaft indicated that the engine was operating at impact. Examination of the airframe and engine revealed no evidence of any malfunctions or failures that would have prevented normal operation. Visual meteorological conditions existed in the accident area at the time of the accident. Mean winds at 10,000 feet were from 220 degrees at 15 to 20 knots; some gusts of 25 to 30 knots may have occurred. Moderate turbulence and downdrafts of at least 400 feet per minute probably occurred at the time and in the area of the accident. The magnitude of the downdrafts likely exceeded the climb capability of the airplane, which, at a density altitude of 13,000 feet, was about 300 feet per minute.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot’s inadvertent encounter with downdrafts that exceeded the climb capability of the airplane. Contributing to the accident were the downdrafts, high density altitude, and mountainous terrain.

There’s a few open questions on this but I’ve gone on long enough, so I will address them in the next post. It’s not finished yet and I have almost 7,000 words worth of notes, so if you have specific issues that you’d like more information on, please feel free to leave a comment and I’ll add what I know, if I know.

EDIT: The follow-up post is now here: More About Steve Fossett.

How healthy was Fossett? FAR 91.211 says oxygen is required if at cabin pressures of 12,500 feet for 30 minutes; I’m wondering whether some combination of age (63) / health and the huge gap between real and pressure altitude could have produced enough hypoxia to affect his judgment or even his flying skills. I’ve never done the take-off-your-mask-at-low-pressure test, but I’ve read about how people recorded under those conditions sound and look.

I’m also wondering how durable ELTs are supposed to be; since they don’t record anything, I can understand not being as durable as “black boxes”, but the ones I remember were small enough that they should not be easy to crush.

And I see I have tangled pressure and density altitude — but as described (fewer molecules per volume) I’d think density altitude would also affect oxygen availability. (This is beyond my area; I worked in biochemistry rather than physiology.)

For physiology it’s pressure altitude that’s important, not density altitude. Density altitude is a function of pressure altitude and air temperature. The outside air temperature is important for the performance of the aircraft. But inside your lungs, the air temperature is pretty much equal to body temperature regardless of outside temperature. Thus, outside temperature is not relevant to the amount of oxygen the pilot gets.

By the same token, atmospheric humidity impacts engine performance but not pilot — inside your lungs the humidity is always 100%.

I just spent some time searching online and can’t find any analysis of the crash site satellite images in order to help us understand why the crowdsourced search of images didn’t work out. Was it because the fabric burned and the frame was basically invisible? It sounded like maybe there was a brush fire – was that not visible in the satellite photos? Please let me know if you see anything written about that aspect, it would be interesting to hear about since the basic conclusion was that the crowdsourced project was a major distraction due to all the false tips.

To read about the demise of Steve Fossett, now in more detail than in the press reports at the time, still is very sad.

I wanted to post a comment about the possibility of hypoxia, I see that CHip pipped me.

The effects of oxygen starvation are becoming more pronounced with age and it will take longer to overcome the effects of alcohol consumption or a health problem. Insofar as I am aware (I am not a member of the medical profession) a lack of oxygen in the blood can have a more prolonged effect at higher altitudes, even if the person was technically totally sober at ground-level.

Even a slight cold, or fatigue, also can exacerbate the effect of hypoxia.

This need not mean that the pilot was incapacitated but it can have an effect on the reaction time and even the accuracy of responses.

I have operated a Cessna 310 at those altitudes. It was in the mid-seventies. We were obliged to: we were on a flight from Berlin Schoenefeld to Moscow. In fact, we had been obliged to fly from Amsterdam to Copenhagen and from there to East Berlin, the corridors from West-Germany were closed to any operator except US, British and French. We had to collect a Russian navigator who reeked of tobacco and garlic. We were at FL 090 when he talked in rapid Russian and told us to climb to “Flight level 5000 metres”. This equals FL 150 or 15000 feet. When we protested because the 310 was not pressurized and was powered by piston-driven propeller engines his curt response was: “You climb to 5000 metres or you will see MIG – very close!”

The 310 had a very good autopilot, but the performance was very clearly lacking and we were worried about the risk the prolonged stay at this pressure altitude could pose to us, even if Sergei (the name we gave him as he never gave us his real name) did not seem worried.

Did it affect us? I cannot possibly say but I was in my mid-thirties and never smoked.

The 310 had fuel injection, like the Super Decathlon. I have flown a Bellanca Champion, I believe this was the fore-runner of the Decathlon.

The performance of any aircraft at high altitude degrades. In this context, I challenge the stated “300 fpm” climb at 13.000 ft because this is the OPTIMUM. Aircraft like these are not really designed to be operated above 10.000 feet and the aerodynamics become critical. The data mentioned in the performance section of the manual are probably calculated using optimum circumstances. If tested at all in a real flight, again they were determined under ideal conditions with an aircraft in optimum condition by a factory test pilot. Granted, Fossett was an experienced test pilot but not on a mission to test all the parameters on behalf of the manufacturer. And was he in optimum physical condition?

At the altitude that the aircraft may have been cruising at, there would have been but a small margin above the stall speed.

If the pilot still was attempting to climb, this may well have brought the flight into the “coffin corner” where due to the low air density the engine would have been low on power and the wings low on lift. On top of that, the aircraft would have had a very small margin above stall speed and may also have been in the aerodynamic trap where when approaching stall speed the drag rises, needing more engine power in order to recover. Engine power which at that altitude no longer would have been available. So the only way to recover would have been to dive. And in the thin air, even that would have required more space below than at low altitudes and would not have been available with mountains all around and under the aircraft.

Fossett may have been aware of the danger he was in and attempted a turn. If at such an altitude a turn is initiated the aircraft will at once lose a lot of lift and will descend, probably instantly. In such a situation, if the pilot’s reactions are a bit sluggish, (s)he may not immediately realise that the aircraft is losing a lot more altitude than is safe. Combined with possible downdrafts, this would have made a collision with terrain all but unavoidable.

PS: Fossett’s qualifications are listed as him holding an “ATPC”. Ihave never heard of such a licence. Usually it is known as an “ATPL” or “ATP” in the USA. Is this something new?

Many years ago I had an instructor (Robert Briot), an Aerospatiale test pilot. He was one of the best instructors I ever have been taught by. He only held one single type rating, but it was the most impressive one I can imagine. It simply stated “Any Aircraft”.

ATPC (Airline Transport Pilot certificate) seems to be an alternative name for ATPL/ATP used in the United States, for example:

http://www.flightschoolsmaine.com/airline-transport-license-maine.php

To me it seems like he flew into a position, due to downdrafts, density altitude, and high winds (winds that were later so strong as to necessitate the cessation of search and rescue operations shortly after the accident) where he was unable to gain any altitude but was also unable to descend due to rugged terrain. It appears as though he may have seen the rising terrain and attempted a 180, only to be met with more rising terrain. This was possibly obscured due to weather, hypoxia, stress, and/or cockpit visibility. This is entirely speculation though.

I don’t doubt that, AndrewZ but in more than 40 years’ flying I never heard an Air (or Airline) Transport Pilot Licence referred to as an “ATPC”.

Just goes to show: there is always something new to learn !

In terms of determining if this was a “crash” or “controlled flight into terrain” there any information that used the dynamics to assist in the aircraft likely impact status. I mean using the paint scrape, the aircraft resting point together with the engine resting point. It there enough to differentiate between controlled or uncontrolled flight? If there is suggestion of controlled flight it could indicate that the pilot was not entirely incapacitated. I have the suspicion that hypoxia would not facilitate “controlled” flight! Was the engine examined? Blades missing suggest rotation on impact with ground! Were any of the missing blades located? Was anything indicated by the examination of the engine? Does seem to be lack of information!

I don’t entirely buy the Hypoxia – yes the effects can be extreme – would a pilot of such experience allow himself to be exposed to risk of that type – I think with his background and experience/knowledge of altitude awareness is unlikely to have been caught out! There have been documentaries about the RAF altitude training which seem to initiate a much higher altitude. However the fittest of the fit can succumb to the sudden on come of illness. one of the photos taken at a right angle gives the impression that the terrain might support an emergency landing. If your senses were impaired for any reason would you not be looking to set down urgently. Not sure about the negative outcome of the funded investigation. Surely it could be done easily using map locations grid techniques as done by armies before satnav arrived. Does it not require an automatic investigation by the air accident boys? If not it should be.

2/27/24

Good Day NO I am not a Pilot.

There seem’s to be many story lines out there as to when Steve Fossets left the Private Nevada Airport. Was it 8:00, 8:25, 8:30, & Then 8:45am?

2> Chief Pilot at Private Airbase said Fossetts going out for Spin? What does thta mean ior play on words? But but crashed at 09:07AM But then Steve was spotted by many near same Nevada Private Airport at 11:00am at 150-200 above the ground but then heading North. I am wondering if Steve was having problems trying to land the A/C with a Joy stick instead of the traditional 2 handed mechanism

The Chief Pilot at Private Nevada Airport said Steve was not I repeat was not experienced in flying the Aircraft with a Joy Stick, So why was Fossetts flying it? Why wasnt anyone trying to contact Steve by Radio at the 2 hours has passed?.. Somethink about this whole things seem very confusing.

If Fossetts had been flying around area 51 and saw somethink he was not suppose to see & His plane was brought down by Military? As Tracker lost him at 09:07Am

Why was the Tracker reporting Fossetts Aircraft at 9:07 when it should of been Tracking Fossetts as soon as it took off from Nevada airport

Why were Tire Waps Taken off the plane???

It just seem to me that Steve Fossets Planned on taking his own life By numerous things he refused to put on aircraft. 1>Fossets did not bring his watch with emergency beeper in it. 2>He refused to take an emergency case with him, 3> The Tire Wraps were taken off, 4>Refused to make out a Flight Plan of Fossetts Activites and Arrival Time Back at Private Nevada Airport. 5>Steve Wife Peggy both had Bad argument at Breakfast about Steve taking off when that was not planned and that both of them were suppose to be leaving at 10:00am Back to their home in Beaver Creek, Colorado, instead Steve made other plans to fly..and did…..

Steve was looking for dry lake bed for New land Speed Record and yet in another news paper said that Fossetts was not looking for Dry Lakebed then What was he lookiing for??.. At 10,000 feet It required to be on Oxygen Was Steve suppose to be on Oxygen???

According to Steve Fossets Land Speed Record Crew They were going broke building this Jet Powered Car, & was not sure how Long Peggy was going to put up with these excessive costs..