Overloaded, Overspeed and Out of Fuel

The situation started quietly: a Boeing 757 inbound to Newcastle International Airport (NCL) was asked to do a go around: break off the approach and try again.

The Thomas Cook aircraft was a Boeing 757-237 registration G-TCBC. There were seven crew on board and 235 passengers. The crew was scheduled for an early morning flight from Newcastle to the Canary Islands, landing at Fuerteventura and returning to Newcastle that afternoon. They could expect to be home for suppertime.

The Commander was 56 years old and held his ATPL with 13,374 flying hours (1,380 on type). He’d spent two and a half years flying the Boeing 757 before the incident. Prior to that, he’d flown Airbus aircraft for over thirteen years. He said he’d reached a stage where he felt comfortable with the B757. His First Officer had been rated on the Boeing 757 for over five years.

They reported for duty that morning at 0500 hours. The Captain said they were as well-rested as could be expected for that time of the morning. His mindset about his job was less than positive.

He sensed that the airline was in turmoil due to a major internal re-organisation programme. The direct effect for him was that he had been told that he would be one of several captains who would be demoted to first officer in March 2014 and that his salary would reduce significantly. He was unhappy about this impending change and the matter weighed heavily on his mind at work, despite his best efforts to ignore it.

The day’s flights were uneventful until they were on final approach to Newcastle. The Captain was the Pilot Flying. The runway was wet and the Automatic Terminal Information Service included a pilot report of windshear at 500 feet which had caused his aircraft to lose 15 knots of airspeed.

The Boeing 757 was set up with the landing gear down and flap 20, preparing to land with flap 25 as per Standard Operating Procedure. After a slightly late turn onto the intercept heading, the aircraft overshot the centreline in the process of capturing the localiser heading. Air Traffic Control noticed the overshoot and gave a new intercept heading.

The Captain thought there was a technical fault and commented on this to his First Officer repeatedly over the next few minutes. After the incident, no evidence of a system fault was found. The investigation found that the Captain believed that he’d experienced more technical problems than was usual for the past few months.

The flight crew had clear sight of the runway and the aircraft landing ahead of them. Everything seemed good.

Then the aircraft in front reported a possible birdstrike on the runway. Air Traffic Control immediately called the Thomas Cook Boeing 757 and instructed the flight crew to go around.

The Captain responded by saying “Go around” three times. He applied maximum thrust and disconnected the autothrottle.

The First Officer hadn’t expected a go around when everything looked fine and simply wasn’t sure what was happening. He heard the Captain’s repetition of the go around but it was not a standard call. The Captain’s call should have specified a flap setting, which would serve as the First Officer’s first instruction. He wasn’t quite sure what to do.

Air Traffic Control instructed the aircraft to climb straight ahead to 3,500 feet above mean sea level. The standard missed approach procedure, which both pilots would have reviewed before the flight, was to climb to 2,500 feet.

The controller probably meant to simplify the go-around procedure for the crew but this instruction came in as the crew were trying to initiate the change in plans and under a high work load. As a result, it was just another distraction.

The go around was badly handled. The Captain did not press the G/A (go-around) switch which would have helped configure the aircraft for him; specifically, it would have cleared the localiser and glideslope data until they set the aircraft up for the new approach. The Captain also did not disconnect the autopilot as a part of his initial response. So now, the autopilot was still trying to track the localiser and glidescope for a landing which they’d already missed.

Takeoff/Go-around switch – Wikipedia

The go around setting is used when an approach is taking place. If a pilot finds that they are unable to land, activating this switch (pushing thrust levers to TOGA detent) will increase the power to go-around thrust. Most importantly, the TO/GA switch modifies the autopilot mode, so it does not follow the ILS glideslope any more and it overrides any autothrottle mode which would keep the aircraft in landing configuration. On Airbus aircraft it does not disengage the autopilot, but causes it to stop following the ILS and perform Go Around maneuver automatically. In an emergency situation, using a TO/GA switch is often the quickest way of increasing thrust to abort a landing. On Airbus planes pushing throttles to TOGA detent does all regarding flight path and speed.

However, instead of using the TOGA switch, he disconnected the autothrottle and applied maximum thrust. At full power, the aircraft accelerated and continued to descend.

The speed was 187 knots and still increasing when the Captain said “go around” again and finally disconnecting the autopilot. An unexpected go around is always stressful and now he had to fly the aircraft manually and force himself to disregard the commands coming from the flight director, which was still set up for the approach. He did not tell the First Officer of the configuration changes and didn’t say anything as he disconnected the autopilot.

The First Officer didn’t check the panel so he didn’t realise that the aircraft had not been set up for the go around. Standard operating procedures had broken down and he became confused. His job, as pilot monitoring, was to watch for discrepancies, especially speed. He was aware that the go-around call was incomplete and that he hadn’t modified the flap settings but instead of querying the situation, he responded to the Air Traffic Control call, confirming that they would climb to 3,500 feet, and then he input the height on the mode control panel.

The First Officer was selecting the new altitude when the master warning alert sounded. He cancelled the master warning. He didn’t spot that the autothrottle had been switched off, although at this point he noticed that the Captain had disconnected the autopilot. The First Officer looked at the Captain to make sure everything was all right, surprised that he was flying the go around manually.

The aircraft reached the Flap 20 speed just after the autopilot was disengaged as the aircraft pitched up. Although the gear was retracted, the Flap 20 setting remained for a further 30 seconds.

The Commander called for Vref+80 climb thrust. Vref is the speed for the aircraft which is the safe manoeuvre speed with flaps up. In this instance, Vref was 125 knots so plus 80 means that the Captain wanted to go 205 knots.

But the First Officer became flustered when he couldn’t set the speed.

Because the commander called for a target speed of VREF+80 and climb thrust, the co-pilot tried to select the relevant speed on the MCP. However, he was unable to open the speed window to do so. He recalled that before the departure from NCL, an engineer had said the previous commander had mentioned having difficulty in viewing one of the digits in the speed window, so the co-pilot wondered if there was a technical malfunction. Meanwhile, although he was aware that the speed was increasing rapidly, he was trying to retract the flaps and failed to monitor the speed adequately.

Although he’d flown the Boeing 757 for over five years, he had very little experience performing a go around and couldn’t remember having practised much in the simulator training. Now he’d become overloaded. He had too many tasks at the same time; the human response to this is to limit the amount of processing and over-focus (or fixate) on a single task. He lost all overview of the situation and of his role as pilot monitoring.

The limit for safe manoeuvring of the aircraft with flaps set to 20 is 195 knots. The aircraft had exceeded this by 18 knots before the flaps began to retract. The aircraft speed remained above the flap limit speeds up until the point when the flaps were fully retracted. The aircraft reached 287 knots before the thrust levers were set back to idle position from the go around.

That’s what is known as overspeed: the airspeed has exceeded a safe limitation. In this case, the safe speed for the extended flaps was exceeded, which can cause damage to the flap system. In the case of a flap overspeed, a full inspection must be made of the flap system before the aircraft can fly again.

The Captain was doing his best to climb and maintain 3,500 foot above mean sea level flying by hand. He later described his First Officer as “stunned” and said that he was not offering the support that he could have.

The Captain asked for the autopilot to be engaged but that proved problematic as well. They didn’t speak, but the flight recorder shows that the autopilot was repeatedly engaged and disengaged over the course of the next few minutes. This may have the result of movements on the control or that the Captain was inadvertently disengaging it using the pitch trim before realising it had engaged.

Meanwhile, as the go-around switch had never been set, the Flight Director modes for localiser and glideslope were still set. The only other way to clear this would have been to turn the flight director off and on again. So even if the flight crew managed to engage the autopilot, it would still be trying to track the localiser and glideslope for the active runway, now behind them.

They were in a mess.

They were lucky that although the aircraft was flying well above the safe limits for the flaps, the flaps retracted normally. As they retracted past flight 1, the leading edge slats began retracting. However, due to the speed, the leading edge slats failed to fully retract. They stopped, partially extended. A caution message appeared on the Engine-Indicating and Crew-Alerting System (EICAS) but neither flight crew member acknowledged the caution.

It took six minutes for the First Officer to set up the speed window and autothrottle and the autopilot so that the autopilot could remain engaged.

Meanwhile air traffic control gave the flight crew vectors to lead the aircraft downwind under radar control for another approach to Newcastle. The workload was such that the aircraft was flying almost 500 feet below their cleared altitude (3,500 feet) and neither pilot noticed.

The First Officer suggested that they enter a holding pattern. The Captain decided not to and instead said they should extend the downwind leg. The First Officer informed Air Traffic Control that they had a slight technical problem.

The Captain asked how much fuel was remaining and the First Officer told them that they had 3,600 kg.

The First Officer was right to ask for a holding pattern: the flight crew were racing behind the plane and a holding pattern would give them the chance to find out what was going on. Although the Captain later stated that his First Officer seemed flustered and not giving full support, he turned down this opportunity to get caught up. By extending the downwind, the Captain made them do a whole new set of calculations. This solution did not relieve any of the pressure on the crew.

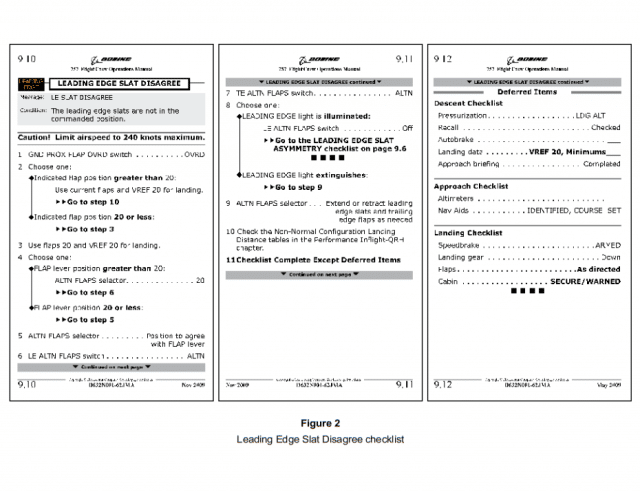

The First Officer spoke to Newcastle control on the radio as he started the Leading Edge Slat Disagree check list. He followed the first four steps correctly but at step five he made a mistake. The checklist said that the alternate flaps selector should be set to agree with the flap lever. He should have set the selector to UP as the flaps had been retracted. Instead, he set the alternate flaps selector to flap 1.

Eventually the automatics were successfully engaged but the slats remained partially extended due to an exceedence of the limiting speed by a significant margin. The co-pilot began the relevant Quick Reference Handbook checklist but he was frustrated by his poor performance prior to that. Interruption caused him to lose his place in the checklist and instead of starting again, in accordance with SOPs, he struggled to find where he had got to. The similarity in presentation of steps 2 and 4 made this quite difficult. Step 5 required the alternate flaps selector to be positioned to agree with the flap lever. The flap lever was in the up position but the co-pilot set the alternate flaps selector to flap 1, possibly as a result of his heightened anxiety.

In step six, the leading edge flaps were set to alternate. The First Officer did this, which meant that the leading edge flaps ran to the commanded flap 1 position.

This cleared the Leading Edge Slat Disagree message… but now the Trailing Edge Flap Disagree message lit up.

The First Officer hadn’t completed his checklist but the Captain saw the new caution and told the First Officer that he should change to the Trailing Edge Flap Disagree checklist.

Step seven, the next step of the checklist, would probably have made it clear to the First Officer where it had all gone wrong but he never got that far.

He started the Trailing Edge Flap Disagree checklist. This time he made it to step three before being interrupted by a radio call from Newcastle Tower. The extended downwind meant that the aircraft had now left controlled airspace.

It would have been nice if Air Traffic Control had notified them of this before they’d made it that far, giving the flight crew a choice to stay in controlled airspace to retain the best traffic separation service. As it was, they continued.

Standard operation would be that the Pilot Flying deals with the radio while the Pilot Monitoring goes through the checklists but neither flight crew ever seemed to consider the division of duties.

The First Officer acknowledged the ATC call and went back to his checklist. The Captain interrupted him again, asking for more flap. He was increasingly convinced that they had a flap fault and wanted to confirm the problem. “Let’s go for flap 5,” he told the First Officer.

The First Officer stopped the checklist and tried to move the flaps with the flap lever. He was clearly disorientated as he selected both the flap lever and the alternate flaps selector to the flap 5 position. Nothing happened.

The Captain did not notice that the First Officer had mishandled the flaps but he did notice that the flaps were not moving. This was the confirmation he was waiting for: they had a flap fault and would have to do a flapless landing.

The First Officer never completed the checklist. Had he ever completed steps four and five, the flaps would have been controlled and referenced to the alternate flaps selector: that is, he would have been led to diagnose the actual fault which he had caused.

No other flap/slat issues were recorded for the remainder of the flight and the landing was made using flap 30. Other than the conditions associated with excessive speed and partial slat extension, the flap and slat parameters reacted as expected for the given crew selections.

The Captain needed to decide what to do.

He explained later that he had a landing distance of 1,600 metres in his head for a flapless landing, and that the week before, he’d seen an aircraft landing at Newcastle with flap 20 and it had appeared to use much more than this. He knew that the Newcastle runway didn’t have a stopway for overruns. He didn’t like the idea of a flapless landing on that runway, which was wet and had reported windshear earlier.

The flight’s alternative airfield was Edinburgh but he knew the runway there was not much longer than Newcastle’s.

“That’s all the flap we have got,” said the Captain. “We need a longer runway, don’t we.”

The First Officer knew where the closest longer runway was. “Yeah, we need Manchester, don’t we?”

It seemed obvious to both of them: so obvious that neither checked the Calculation of Operational Landing Distance which would have told them that the runway at Newcastle was plenty long enough for a flapless landing. There was no discussion of the decision, let alone a review.

They needed 2,000 kg of fuel to fly to Manchester, which meant using the final reserve fuel. The Captain decided that they must divert immediately.

The First Officer agreed and informed Newcastle that they could not get the flaps down and that they were diverting to Manchester.

Fuel Emergency (EU-OPS 1.375 b)

The Commander shall declare an emergency when the calculated usable fuel on landing, at the nearest adequate aerodrome where a safe landing can be performed, is less than final reserve fuel.

The Captain had never dealt with a low fuel situation but he told investigators that he knew that he needed to make a MAYDAY call as soon as he was aware that they would need to use final reserve fuel. He could not explain why he did not do so.

Thomas Cook, the operator of the flight, did an internal investigation to try to understand how the situation has deteriorated from a simple go around at Newcastle. They came to the conclusion that the pilots felt more in control of the situation once they had made a decision, so although they knew it meant landing with less fuel than normal, they accepted this as a necessary part of the solution.

Meanwhile, Air Traffic Control instructed the flight to turn onto heading 230º and climb to FL100 and asked what cruising altitude they would like. The flight crew decided it was better to stop the climb at 10,000 feet. The First Officer selected Flap Up without going back to his unfinished checklist. He forgot about the alternate flap selector which he’d set to flap 5, so the flaps remained partially extended. Neither pilot ever thought to check the pressure settings.

They proceeded with the flight.

The forward fuel pump low pressure light illuminated on the fuel panel. The First Officer commented on this but no action was taken. Meanwhile, the Captain called in the cabin manager for a briefing on the flaps situation and to explain that they were diverting to Manchester.

Air Traffic Control cleared the flight direct to Pole Hill VOR.

The flight crew levelled off at what they thought was FL100, 10,000 feet above sea level. However, they hadn’t changed the pressure settings and so the pressure was still set up for Newcastle. When the aircraft levelled off, it was 420 feet above the cleared level.

Now the First Officer found that he could not program the new route into Route 1 in the flight management computer. The Captain used raw data to navigate towards the Pole Hill reporting point.

The commander used the heading select to navigate by hand towards the Pole Hill reporting point. Clearly frustrated with all the technical difficulties they were experiencing, he decided that they needed to declare a MAYDAY.

They should have done this as soon as they knew that the aircraft was going to land with less than final reserve; that is, when they diverted for Manchester.

The First Officer told Air Traffic Control but didn’t use the standard phrasing. Instead, he almost conversationally added “and we want to declare a mayday” at the end of a call.

The controller acknowledged this with “Roger” and then followed up. “Have you got any more details for the paramedic?” He had clearly presumed that there was a passenger issue on board as he had no information to lead him to believe that the flight was in difficulties.

The First Officer explained that they didn’t need a paramedic but that they would be making a flapless landing at Manchester. He did not mention the fuel situation. His attention was split between the flight management computer and the radio calls. As a result, his performance was extremely poor.

He had lost confidence in his own ability and he had probably reached an over-aroused mental state, where his capacity to think straight had started to deteriorate. Like the commander, he was now experiencing a low fuel scenario for the first time. At this point it is likely they were both task-saturated. This helps explain why the After Take-Off Checks were missed.

It’s likely that he couldn’t program the new waypoint in the flight management computer because he hadn’t activated Route 1. In any event, he eventually decided to enter the data into Route 2 which was then activated. The flight crew were finally receiving navigational assistance from the flight management computer for the first time since the initial go around.

That’s when the LOW FUEL caution light and the fuel configuration light turned on. The First Officer then told Air Traffic Control that they were requesting a priority landing due to a low fuel warning. Newcastle Air Traffic Control said they would pass the message on and asked if an emergency was being declared.

The First Officer confirmed this and he was asked to squawk 7700, which is the code for a general emergency. This means that for every controller in the area who could see the flight on secondary radar, it was clear that the flight crew had declared MAYDAY.

At no point did the crew discuss the fuel situation. They didn’t appear to take into account the extra miles they were covering in their approach from east of Newcastle, nor the fact that they would use more fuel because of the non-standard flap configuration for the cruise. They’d decided to stay at 10,000 feet but their predicted fuel burn was based on cruising at 17,000 feet.

The First Officer tried again with the flaps and this time after various selections, he found that the flaps appeared to be working normally. He’d managed to turn off the alternate flap lever, which cleared the disagree indications. He retracted the flaps to conserve fuel and concluded that the flaps were finally back under normal control (although they had been all along).

The Quick Reference Handbook specifically warns against troubleshooting by deviating from non-normal procedures prior to the completion of appropriate checklists. The crew ignored this and made random flap selections without referencing either checklist.

They managed to regain normal control of the flaps, but if they’d followed the Quick Reference Handbook in the first place, they wouldn’t have even had to consider a flapless landing, let alone a diversion.

At any event, their flaps were now clearly working as expected. They’d had a low fuel indication for fifteen minutes and the Captain knew that Newcastle was still the nearest airport. He didn’t revisit the plan but continued to Manchester. He later told investigators that they’d already made the decision to divert and besides, he didn’t think the First Officer would consider a return to Newcastle.

…the commander felt there was little time available to conduct a joint review of the situation but that he did mentally review things himself. He also remarked that the situation had felt unreal and that it seemed to get out of control very easily. He recalled that on a couple of occasions he had tried to offer the co-pilot some reassurance.

The First Officer changed frequencies to Scottish Control and identified the aircraft. He did not mention the MAYDAY. There was no response, but neither of the flight crew seemed to notice. They had now realised that they’d never done the After Take-Off Checks after the Go Around at Newcastle and went through the checks, including resetting the pressure and descending to FL100.

After a further discussion about the flaps, the crew agreed that they should be able to land normally with Flap 30 but they would slow up early just in case.

They were unsure whether there’d been a flap overspeed or not and were perplexed as to why the automatic systems had not worked as expected.

Scottish Control did not realise the aircraft was on frequency until six minutes later, when the First Officer called again to request direct routing to Manchester.

The flight was given clearance for a direct 10-nautical-mile final into Runway 23R at Manchester. The Captain commented that they needed to do something about the fuel, over fifteen minutes after the low fuel caution for the right tank. This was the first reference in the cockpit to a fuel imbalance.

The First Officer didn’t respond, as at that moment Air Traffic Control gave them the weather at Manchester airport followed by the descent clearance.

After the call, the Captain asked for the fuel to be balanced. Investigators believe there was an imbalance of close to 800 kg by this time. The First Officer opened the fuel crossfeed and turned off the right fuel pumps without referring to the Low Fuel checklist. Neither seemed concerned about their fuel consumption.

It seems that as the flight crew had already accepted that they were landing in a low fuel situation, the warnings were treated as expected consequences of the solution. But if at least they’d referred to the Fuel Configuration checklist at that point, as per standard operating procedure, it would have referred the crew to the Low Fuel checklist and they might have paid more attention to the fuel levels in the right tank.

The aircraft started its descent. Ten nautical miles from touchdown, the fuel crossfeed was closed and the fuel pumps turned back on.

Following the Low Fuel checklist would have meant that the crossfeed was left open with all pumps on until landing. Instead, the crossfeed was only open for eleven minutes. As the thrust was at minimum for most of those eleven minutes, there was not enough time to balance the tank levels.

By this time, the Captain had realised that their fuel levels were critical. “We’re committed to land now, we have to land,” he said, and then later, “We don’t want to go around. We can’t.”

The First Officer acknowledged the situation. Normally, the crew would have discussed the Flight Crew Training Manual notes regarding an approach and landing with a low fuel warning. At the very least, they should have discussed the possibility of a further go around, rather than just dismissing the possibility.

Manchester Air Traffic Control should have been told that their fuel situation was critical. Nothing was said after the initial request for direct routing due to low fuel.

From the Thomas Cook internal investigation into the situation:

An important point here is that both crew felt so much better about the situation after the decision was made, it made them reluctant to question it further (if unconsciously). The choice to go to Manchester ‘felt’ very good and this affect probably duped the crew into a false sense that the choice was better than it was in reality, and stopped them reviewing or scrutinising it.

It is probable that the criticality of the fuel situation was never properly realised for a number of reasons; partly due to being consumed with a reflection on earlier mistakes, partly due to a reticence to discuss further problems during the flight (and therefore a tacit reassurance from each other), and partly due to unfamiliarity around diverting and what to expect. However the main reason is probably that the crew viewed the fuel state as being planned as part of the decision to divert…….Because below-minimum fuel was part of that ‘very good’ decision, and the fuel state progressed ‘as planned’ in line with that ‘very good’ decision, the actual criticality of the fuel situation did not make the impact upon the crew that it might have done. This even applied to the EICAS message and failure to run the low fuel QRH.

There’s a happy ending to this one. At 16:49, the aircraft landed safely on flap 30 and taxied to the stand.

There were only 200 kilograms of fuel in the right tank. With the crossfeed valves closed, the right engine was dangerously close to flaming out and certainly would have if they’d been asked to go around.

The day was over for the flight crew. The Captain made a note in the technical log that they were unable to select a speed in the speed window after the go around. He also noted that the LE Slat Asymmetry and Flaps Disagree warnings had been displayed. He did not isolate the cockpit voice recorder or preserve the flight data recorder data although he later stated that he was aware that it was a serious incident. He didn’t debrief the First Officer or review the situation with the crew before dispersing. He didn’t fill in his report immediately as he was in the habit of leaving them for a couple of days. He did attempt to contact the Duty Flight Operations Manager but failed.

On the way home, he realised that he hadn’t told the engineers about the possibility of a flap overspeed event. He phoned in and it was added to the technical log.

The engineers analysed the flight data and discovered that the flap 1 speed limit had been exceeded by 46 knots. Thomas Cook started an internal investigation as the details began to come clear. The day after that, they reported the flight to the AAIB who began their own investigation immediately.

The internal investigation included the following report from the Captain:

He remembered that he called “go around”, but did not state “flaps 20” and that he advanced the thrust levers. He knew that he needed to do something with his thumb, but instead of pressing the Go Around switch, he said he must have disconnected the autothrottle.

The AAIB computed the minimum landing distance for the 757 as 1,455 metres for a flapless landing. If you add a safety margin of 15% in case of technical emergency, that’s a total landing distance required of 1,685 metres. Newcastle’s runway is 2,125 metres.

What should have been a straight-forward go around at Newcastle Airport went very wrong as a dozen small issues cascaded into an avalanche. The niggling feeling that he needed to do something with his thumb led him to disconnect the autothrottle rather than hit the Go Around switch, meaning that he had to advance the thrust levers manually. Because the G/A switch wasn’t selected, the autopilot had to be disconnected in order for the aircraft to climb. And so it went on: a simple mistake in the correct sequence of pressing buttons came damn close to risking fuel exhaustion in the right engine.

Thomas Cook have adjusted their training for go arounds to include the advice that the flight crew need to take their time and discuss their intended actions, and if necessary to re-engage the autopilot first. Obviously it needed to be said.

This incident is especially interesting because unlike many recent go-around incidents, this was not a case of the pilots being unable to hand-fly the plane. On the contrary, the Captain was clearly able to go around and return into the circuit under manual control, despite the Flight Director working against him. He then continued to hand-fly and navigate the Boeing 757 to the first waypoint en route to Manchester. In this case, the combined lack of knowledge of the flight crew regarding the automatic systems in the aircraft and an inexplicable lack of adherence to checklists caused them to get into such a muddle that they became totally unable to fly the plane safely.

The original accident report can be read on the AAIB website.

For more like this, pick up the first book in my series, Why Planes Crash. Why Planes Crash Case Files: 2001 covers eleven incidents and accidents in detail from all over the world in 2001.

This crew seemed to have made a series of blunders that would seem to point to serious flaws in the standards of crew training. These pilots were experienced enough, at least on paper. But the scenario as described makes me wonder how they ever got through the simulator checks. Crew coordination was a total shambles and reading it nearly makes me physically nauseous. Sylvia, in your article I miss a mentioning of what sanctions were taken. But I would not be surprised if it spelled the sad end of their career.

Please reassure us that Thomas Cook has cleaned up their crew training. I would not be happy as a passenger in one of their aircraft, having read this.

I give full credit to Thomas Cook for immediately reporting the incident when they could have sat on it. I don’t know about what happened after but I’d be very surprised if the Captain is still with them.

That made really interesting reading with the cascade of problems. Thanks for taking the time to write it up.

Sylvia,

The problem I have with Thomas Cook is that the report as you posted it very much points to below standard when it comes to crew training. During what should have been a relatively routine go-around the crew – both captain and F/O – did not adhere to any form of recognisable crew coordination or SOP’s.

This is your second posting in a row where the crew failed to adhere to standard crew coordination procedures.

Thomas Cook would have risked losing their operating licence if they had not sent in the report.

The more things change the more they stay the same,human error will always be a factor in flying,history has proving that over and over.

Well George, a truer word has seldom been spoken in jest !

SOP’s can bring the risk of human error down to very acceptable levels. Some people want to eliminate pilots from the flight deck. That, in theory, may be true but it will also introduce the risk of exposure to systems failure. So far, only humans are capable of the lateral thinking that can save the day.

There are many examples of situations where a well-trained crew able to save the situation caused by multiple failures.

But it all depends on the efforts that the airline’s training department will put in.

Major airlines can be very pedantic when it comes to SOP’s. I have had my head bitten off by a line check pilot. We were departing from a regional airport. My F/O was a young woman, just released on line. She was very busy with the paperwork, I was the P/F.

We were starting to run late, so I grabbed the loadsheet which I could do in a short amount of time – I had DESIGNED the darned form !

After return at base we got a de-briefing and I was torn apart by the check pilot (who also was the fleet captain). Why ? Because it was SOP for the non-handling pilot to do the paperwork and I had therefore “breached protocol”.

It resulted, two weeks later, in an unannounced visit from a CAA inspector who had reacted to a negative report the check captain had sent in about me. Luck was with us: I had the same F/O and we did not need to be told how to behave. Fortunately, the CAA inspector wrote a glowing report which neatly balanced out the previous one (it was also SOP in this airline to allow crew members periodical access to their files).

Sadly, the young F/O left our airline not long after. She was offered a command on a Shorts 3-30 cargo operation. She was killed a few months later during night ops at Paris CDG when a miscommunication with ATC caused her to taxi on to the runway before cleared. I do not know the details, but from extensive flights in and out of that airport (and other French ones) I know that the mix of languages in ATC can be potentially lethal. When she realised the error she was just too close to the runway and the wingtip of a landing aircraft sliced through the cockpit of the Shorts.

She was a nice person and as a new captain just at the beginning of her career.

A more relevant addition to this saga is one of my own, more direct experience.

In the early 1980’s the company I had worked for for about 9 years suddenly decided it could no longer afford their executive jet – a nearly brand-new Citation 500. It was sold to Italy. The new owners employed me on a temporary basis. Their captain was an American, a retired TWA 747 captain. How he had managed to stay alive flying airplanes is still a mystery to me. He was authoritarian, had no crew management skills whatsoever and his piloting skills were dismal. His main skill was blaming others for his errors. So if anything went wrong, it was either myself, reduced to co-pilot status, or if he could not pin it on me, ATC. I could write a few pages on all his antics. His constant refrain was “I am the captain and you will do as you are told”. But the one relevant here is the following event:

We were flying into Milan Malpensa, the home base. The weather was fog. But this captain claimed that he was “Cat 2”. Even though he might well have been with TWA, the C500 was not cat 2 certified nor had he kept up his cat 2 records to keep qualified.

Even so, he insisted on making an approach under conditions that were actually cat 3.

He botched the approach. If handled properly, the Citation could be flown all the way to the ground in zero visibility. I had been made to do this a few times under training – under the hood which I was not allowed to remove until after landing.

But this pilot was totally unable to control the aircraft and at around 50 feet above the runway was forced to go around. We were already at 10.000 feet when my reminders about flaps and gear finally got through: we made the missed approach with gear and flaps down.

I will not go on about it, the owners held this ……. (unprintable) in high regards, but my only regret is that when I finally was forced to leave (there would have been a job but this turd saw me as a threat) I did not give him the smack in his gob that he deserved.

Some very, very poor pilots have crawled through the mazes of the training department of even reputable airlines ! But more and more the airlines have tightened their selection and training process, so it seems surprising that the B757 crew that featured in the above got through.

Very thankful neither of these 2 are flying here in the U.S. Both incompetent and demonstrated ZERO…CRM

– Thomas Cook motto. “Checklists? Who needs checklists”….

To think these 2 idiots held the balance of the very souls in the back is scary….

I’m working on the Bedford crash now, talk about disregard for checklists!

I am not a pilot, but have studied human thinking in another domain and my impression of this story is a bit different.

I’ve studied airplanes and flying a little bit, having been a Civil Air Patrol cadet many decades ago. The process of beginning in a two-seater and progressing up through the ranks to commercial aircraft pilot means that the most drilled-in lessons are not to do checklists or even to communicate with a crew-member.

What I see is two pilots facing a new situation and not having experience, they fell back to tried-and-true methods. That conflicted with all the airplane equipment which is meant to provide for easier long-distance flying or safer landings. It didn’t help them that in this critical situation they would have to turn off some things, so they could get to a work environment with less complexity and certainty.

What this means is that the pilot & co-pilot didn’t necessarily fail. It probably means the people who designed the avionics and flight controls failed the pilots. There is some truth to the old saying, “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks”, especially when you give them 30 seconds to learn the new lesson with lives on the line.

Complexity can be a killer. The human mind has a priority system which developed over eons and none of them involves checklists. That’s not to say checklists are inherently bad. I think they’re especially good when the airplane is sitting on the tarmac. But, as situations change for the airplane, the weather, the airport, the pilots, the ATC or other talkers, it becomes a lot.

I blame the computers, but rather than point fingers it’s really critical to keep improving the systems pilots use, so the pilots and airplanes benefit.

Then we wonder why many people are nervous of flying & trusting their lives with strangers. Just goes to show even the most experienced, & supposedly competent, pilots with multi thousand hours can take a relatively simple procedure & unravel themselves with extraordinary alacrity. Not even slightly surprised in this ever & increasingly digitalised & automated world where it’s all to easy to become, distracted, complacent & negligent. Makes me wonder how many other airline crews could lose the plot over such routine matters. Worrying to put it mildly.