In the cockpit of Southwest flight 1380

On the 17th of April in 2018, Southwest Airlines flight 1330 experienced an engine failure while climbing to cruise altitude.

The aircraft was a Boeing 737-7H4 (registration N772SW) with two turbofan engines manufactured by CFM International. The CFM-7B24 engine has 24 fan blades installed on the fan disk.

The flight departed normally from LaGuardia Airport in New York with 144 passengers on board. The first officer was the Pilot Flying and the captain was the Pilot Monitoring. Both pilots were extremely well qualified and had previously flown in the military (the captain had been a US Navy fighter pilot and the first officer had been a pilot in the US Air Force).

Half an hour later, while climbing to the cruise at flight level 380 (38,000 feet) one of the 24 fan blades in the left engine fractured at its root as a result of a low-cycle fatigue crack.

In the cockpit, the flight crew heard a loud bang and the aircraft began to vibrate. The left engine fan speed decreased from 99.5% to 61.5% while the engine core speed decreased from 97.8% to 89.8%. At the same time, the 737 began to roll to the left.

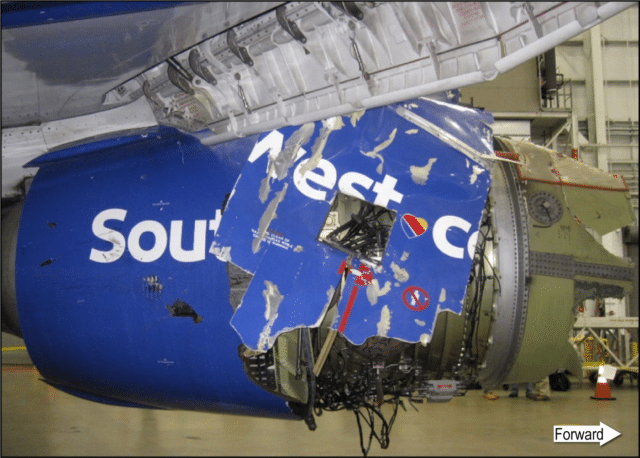

The fan blade impacted the engine fan case and broke into pieces. Blade fragments flew forward and into the nacelle inlet (part of the structure that houses the engine). The fan case became deformed, damaging the inlet further until the inlet separated from the aircraft. The deformity also increased the load on the fan cowl. Cracks appeared on the fan cowl skin and frames and, in a matter of seconds, severed the three latch assemblies which connect the inboard and outboard halves of the fan cowl. Both fan cowl halves separated from the aircraft. One fan cowl was found in the inboard fan cowl aft latch keeper. Pieces of the engine nacelle were recovered from a field on the flight path.

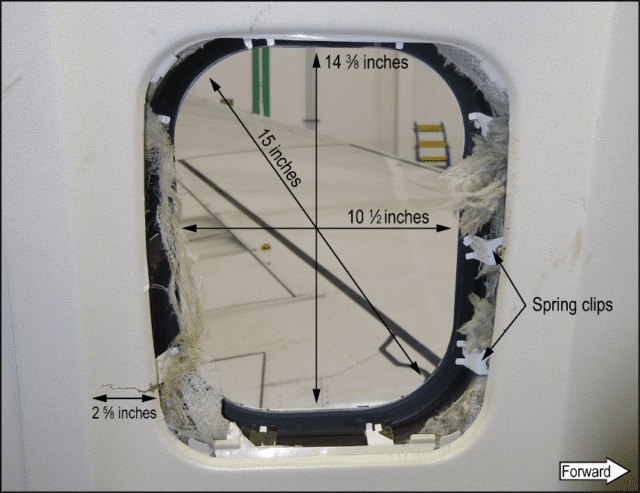

One of the fan cowl fragments smashed into the left fuselage and a cabin window broke, causing a rapid depressurisation. The passenger seated closest to the window was partially pulled out of the aircraft. Cabin crew and passengers were able to drag the passenger back in; however after landing the passenger died of injuries sustained when she was pulled out of the window in the rapid depressurisation.

The cabin altitude warning horn sounded, which meant that the pressure in the cabin had exceeded 10,000 feet. Pressurised flights maintain a cabin altitude below 8,000 feet, so it seemed clear that they had suffered some sort of depressurisation event. Both pilots put on their oxygen masks.

The aircraft continued to roll to the left for a bank angle of 41.3°. The Pilot Flying began to roll the aircraft back to wings level and regained control of the aircraft attitude. The power to both engines was reduced to idle as the flight crew initiated an emergency descent.

The captain initially asked for information on the nearest airport, which was Harrisburg International Airport in Middletown, Pennsylvania (MDT). However, both pilots quickly agreed that their best option was Philadelphia International Airport, which was not significantly further had four runways, the longest of which was 2,000 feet longer than the single runway at Harrisburg, and better rescue and firefighting capabilities. The Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) rating ranges from A to E; Harrisburg, the closest airport, was categorised as B while Philadelphia was categorised as E.

After the flight was cleared direct to Philadelphia, the captain made a public announcement that they were diverting. As the aircraft descended through 17,000 feet, the captain declared an emergency and took over as Pilot Flying with the first officer filling the role of Pilot Monitoring as well as trying to find out what was happening in the cabin. I’ll look at that next week but, for the moment, let’s stay in the cockpit.

This edited recording of the captain working with air traffic controller makes for compelling listening:

As they began their extended final, the captain informed ATC that they needed a single channel and to stop changing frequencies. This was to reduce the load in the cockpit and also meant that she wasn’t explaining her requirements and the situation to new people. The approach controller agreed and told her he’d was just going to let her drive and would clear other traffic out of the way.

Captain: Okay, could you have the medical meet us there on the runway as we’ve got injured passengers.

Approach: Injured passengers. OK. And are you — is your airplane physically on fire?

Captain: No, it’s not on fire but part of it is missing.

Captain: They said there’s a hole and, um, someone went out.

Approach: I’m sorry, you said there’s a hole and somebody went out?

Captain: Yes.

Approach: Southwest thirteen eighty…It doesn’t matter. We’ll work it out there. The airport just off to your right. Report it in sight please.

The first officer, in his role as Pilot Monitoring, went through the Engine Fire or Engine Severe Damage or Separation checklist.

The aircraft landed safely, 17 minutes from the start of the incident.

One passenger was fatally injured and eight passengers received minor injuries.

From the final report:

Metallurgical examinations of the fractured fan blade found that the crack had likely initiated before the fan blade set’s last overhaul in October 2012. At that time, the overhaul process included a fluorescent penetrant inspection (FPI) to detect cracks; however, the crack was not detected for unknown reasons. After an August 2016 FBO event involving another SWA 737-700 airplane equipped with CFM56-7B engines, which landed safely at Pensacola International Airport, Pensacola, Florida, CFM developed an eddy current inspection (ECI) procedure to be performed at overhaul (in addition to the FPI that was already required). An ECI has a higher sensitivity than an FPI and can detect cracks at or near the surface (unlike an FPI, which can only detect surface cracks).

The important point here is that Southwest Airlines flight 3472 had suffered an identical issue with a fractured fan blade almost two years before, in August 2016. CFM International had developed an on-wing ultrasonic inspection technique and issued a service directive for this inspection to take place as a one-off inspection of specific aircraft based on the engine serial number, the number of service cycles or the service time. The engines on N772SW did not match any of the three parameters and so the ultrasonic testing was not done.

After the accident, Southwest announced that they were scheduling ultrasonic inspections of all CFM engines in the fleet. These ultrasonic inspections of aircraft engines, which were done with every fan blade relubrication, identified fifteen blade cracks which had not previously been detected.

Since then, the FAA has issued a follow-up Airworthiness directive for all CFM56-7B engines to undergo repeated ultrasonic inspections for fan blades before they reach 20,000 cycles or within 113 days, whichever occurs later, and then to be repeated every 3,000 cycles. The fractured fan blade on Southwest flight 1380 had accumulated 32,636 cycles since new; the earlier fractures in August 2016 were on fan blades which had been through 38,152 cycles. The additional fifteen cracked fan blades discovered after the accident had an average of 33,000 cycles since new.

From the final report:

Probable Cause:

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determines that the probable cause of this accident was a low-cycle fatigue crack in the dovetail of fan blade No. 13, which resulted in the fan blade separating in flight and impacting the engine fan case at a location that was critical to the structural integrity and performance of the fan cowl structure. This impact led to the in-flight separation of fan cowl components, including the inboard fan cowl aft latch keeper, which struck the fuselage near a cabin window and caused the window to depart from the airplane, the cabin to rapidly depressurize, and the passenger fatality.

The passengers on the flight were given $5,000 each and a $1,000 voucher for future travel with the airline. The captain of the aircraft, Tammie Jo Shults, and the crew were thanked for their heroism at a ceremony at the White House. Shults has written a book about her life and the incident called Nerves of Steel.

The aircraft is parked in Victorville, California for storage. When I was 16, a young man asked me to marry him and move to Victorville and live happily ever after. I declined. However, if I’d known then that a large boneyard facility with hundreds of commercial and military aircraft would end up located there, I might not have been quite so sure of myself.

Part Two: In the cabin of Southwest flight 1380

The crew did a first-class job, that is certain.

But I always feel a bit uneasy if a crew gets high praise for “heroism” from high officials, even the President. It always reeks a bit of political point-scoring.

Yes, I repeat, the crew did extremely well.

But “heroism”? No, that is not my reading, not even of a situation where the professionalism of the crew was instrumental in the successful outcome of an extreme emergency situation.

1. The crew were fighting for, not only the lives of the passengers and cabin crew, but also for their own survival. “Heroism” means, in my book, the inclusion of the willingess to sacrifice the hero’s own life in order to save others. Of course, in a situation like this the death of the cockpit crew would have doomed all other occupants of the aircraft, but that is not what I meant.

2. The pilots were acting as a good, well-trained crew. A lot of experience was no doubt a help and a military background means that they had, in their previous career, been through a rigid selection process in which only the best of the best survive.

There were additional circumstances that all culminated in a good outcome, thanks to a highly professional crew.

Another thing is bothering me: Since the grounding of the 737 Max series an increasing number of aviation experts voice their concern that the ethos of the airline industry has subtly shifted, from safety and engineering standards being the priority to an increasing emphasis on the balance sheet.

A couple of points:

– There seems to be quite a lot of extraneous chatter from ATC. The crew of a damaged aircraft do not need to be told to “start looking for the airport”.

– I wonder if the deceased passenger was wearing a seat-belt? And if not I wonder if that would have saved them?

I happen to know the answer to that one. The passenger was wearing a seatbelt but it did not make a difference in this instance, which was considered beyond what a seatbelt could reasonably hope to achieve (i.e. no fault found)

Maidbloke has a point, but presumably ATC did not realise the extent of the damage that the aircraft had suffered and were trying to be helpful.

Would the deceased passenger have survived if she had been wearing a seatbelt? There is a good chance that the “fasten seat belt signs” had been switched off at the time the engine exploded. And so, it is quite possible that she had unfastened hers. In most airlines the rule is that the senior cabin attendant, when the sign is switched off, makes an announcement which includes a recommendation to keep them fastened at all times when seated.

And so, my guess is that she had unclipped her belt. But I may be wrong there. It was very sad that this coincidence led to her death.

I also want to emphasise that my comments in my first reaction were in no way intended to minimalise the high standard of professionalism that the pilots demonstrated. But the term “heroism”, in my considered opinion, includes a modicum of altruism, putting the interests of others before those of oneself. Yes, it also includes elements of “courage” and “bravery” (I looked it up to be sure to be sure). But ultimately, the pilots did their job. And they did it very well indeed. But then, engine failures and loss of pressurization are among the problems that ALL professional pilots are confronted with on a regular basis. albeit in the simulator.

I have had two rapid decompressions myself, at altitudes of 37000 and 39000 ft (FL 370 and FL 390). One with an oxygen mask of which the elasticity of the straps had suffered over time. So I had to go through the emergency whilst at the same time clutching the mask at my face.

I have had two actual engine shut-downs. OK, we had ample time to go through the checklist, but even so, we had been trained to cope with those situations. Was I as good as those two pilots? I admit: probably not. But: if it had happened to me, would I have acted in a similar manner? Surprisingly maybe, but I would have fallen back on my training and it is quite possible, if not probable, that the outcome would have been the same. Would it have turned me into a “hero”? My answer would have to be: NO. I would have done the job for which I had been trained, in the manner it would have been expected from me.

Metallurgical examinations of the fractured fan blade found that the crack had likely initiated before the fan blade set’s last overhaul in October 2012. At that time, the overhaul process included a fluorescent penetrant inspection (FPI) to detect cracks; however, the crack was not detected for unknown reasons.

Are they going to get to the bottom of that???

Mike,

I am not an engineer, correct me if I am wrong, but insofar as I am aware FPI replaced the old “dye check”. This involved a penetrant liquid to be sprayed on the (metal) part that had to be inspected for fatigue cracks.

The part would be wiped clean, and subsequently be sprayed over with a white developer. The penetrant liquid would still be present in the otherwise invisible cracks. Under the developer the penetrant would turn red and become clearly visible in the otherwise white developer.

This of course would only reveal cracks that were on the surface. I remember whole wing structures like the main spar being X-rayed. Only techniques that can show faults, like fatigue, that have not yet reached the surface of the parts or structure, can disclose faults inside the metal. Again, I fall back on what my old brain still remembers, but I think that ECI is an entirely different process. Changes in the internal crystalline structure of the metal affect the path of an electrical current passing through it, which can be electronically measured to show a nascent defect that can lead to a structural failure.

Anyone willing to expand on this?

I’ve listened to all the publicly available tapes and read all the transcripts of this incident. The captain deserves high praise for exercising her command authority to focus on safely landing the aircraft. One example is telling ATC to stick to one frequency to ease the workload in the cockpit. Another (not mentioned by Sylvia in this article) is her refocusing the FO when he wanted to add track miles to finish a checklist. The captain essentially said, “F**k the checklist, we’re getting this thing on the ground NOW” and did so, safely and quickly. This is a great example of critical thinking: this is a very serious problem, and it is not one we are going to solve in the air, and we have an adequate runway immediately in front of us, so let’s get on the ground and then sort out the checklists. She never forgot what was drilled into all of us from early in our training: aviate, navigate, communicate, in that order.

A couple of comments about ATC procedures are also in order. Kudos to the controller in this situation who also realized that the important thing was to get the airplane on the ground. I’ve listened to a lot of in-flight emergencies on VASAviation, and I’m amazed by: 1) the number of frequency changes given by a single facility when the aircraft is never more than 20 miles from the airport; 2) the “souls and fuel on board” questions (who cares??? It’s more people than you have ambulances, and enough fuel to incinerate them all….respond accordingly); and 3) the failure of controllers to pass on this information to the next controller when handing off the aircraft….they should ask once, and then pass the information along in the background instead of pestering the crew.

If you haven’t read it, the CVR transcript is fascinating as well because it captured a fair bit of conversation among the crew after the aircraft had landed and was being assisted. Reading these comments, and thinking of them in the context of what had just happened, truly gives some insight into the emotions of the crew and humanizes them in a way we rarely see in accident investigations.

I got that also, R. Waskin, that she told the tower “This is my frequency and I’m sticking to it”. Mucking around with radio frequencies is fiddly business, even with pre-programmed settings (which probably wouldn’t have applied to an unscheduled airport anyhow).

“Fuel on board” is important if, for whatever reason, the airplane wants to go ’round and round for awhile, trying to deal with a problem in the air (e.g. bad gear) or reach a distant location. In this case, not important.

“Souls on board” is important if the aircraft goes down somewhere other than the runway (a possibility here) and presuming it comes down fairly gently, how many people should you have to recover before you stop looking for more; which is important to rescue operations. In this case, could have been important.

Re fuel and souls on board, isn’t that information contained in the flight plan? I’m a private pilot, not commercial, so I don’t know what’s in a Part 121 flight plan. If so, and it becomes a SAR event rather than an on/near airport accident, the info re persons on board should be available from Flight Services or dispatch, and in any case, it is not so time-sensitive as to make it worth distracting the pilots. As one who responds to mass casualties, I can tell you that we’re not going to stop looking until we’re sure everyone’s been accounted for, or the probability of survival is nil AND the risk involved in recovery of remains outweighs the benefits depending on the circumstances (weather, terrain, ocean, etc). As to fuel, if it truly is endurance that ATC wants to know, then they need to be trained to ask that way, e.g., “How many hours of fuel do you have remaining?” I have heard recordings asking for hours, for pounds, and for gallons (and if I listened to European incidents I’d probably hear the question in kilos too!). ATC should ask only what they need to know right now to assist the pilots at that moment; all else can wait. They are not shy about telling other aircraft to stand by, stay out of the controlled airspace, or expect ground stops and delays due to an emergency in progress, all of which are tactics which reduce ATC workload. Give the pilots of the emergency aircraft the same consideration.

The details of a flight plan often do not survive even the closing of the boarding gate, much less any in-flight decisions. For example, the cabin manifest lists the passengers who intended to board. The actual load can change in the last few seconds before closing the doors.

In the macabre example of Aloha Airlines Flight 243 (April 28, 1988), the number of souls on board even changed as a result of the accident! But even in cases when no cabin crew have been swept overboard, the best information comes from direct observation.

Counting the souls on board is best done before the wreck or crash, when they are still all confined to the craft and none dismembered or destroyed.

The amount of fuel actually on board is best known to the flight crew. It may not only differ from what was planned, that difference may be part of the incident.

From the final report: “For example, according to CVR information, during the 17 minutes between the time of the engine failure and the time that the airplane landed, the crew was given four frequency changes. Also, ATC asked the crew multiple times to state the following: the nature of the emergency, including whether the engine was on fire; the number of occupants aboard; the amount fuel on board (which the flight crew provided in hours and was then asked to provide in pounds); and the ARFF support that would be needed after landing.”

I’m not certain that ATC did anything different here than what they usually do.

Note the reference to “multiple times” — this is the problem with multiple hand offs. The captain had to repeatedly explain the situation and what they were doing and at no point could she have confidence that the controller-of-the-moment was up-to-date. Reducing frequency changes and passing information along to the next station makes it a lot easier for the flight crew to stay focused on what’s happening in the cockpit. I’ll see if I can find a good example of this to share.

Very interesting story, and excellent comments.

The comments are fantastic!

R.Waskin,

You are absolutely right. This crew did outstanding work. The Swissair crash, where the approach was delayed whilst the crew were trying to sort out what caused the smoke in the cockpit may well have played through her mind. Kudos? Absolutely. I would feel reassured if I were a passenger in an aircraft with her as captain.

Now many years ago an Aer Lingus 737-200 suffered a bird strike immediately after take-off from Dublin. Both engines were damaged. One fortunately kept running, albeit at reduced capacity. The other one was destroyed. I have seen it as it was towed back from the runway after a safe landing. One engine had nearly separated from the wing and was held by what looked like a retaining strap. Boeing had very high praise for the very professional way this incident had been handled and considered that this could have been a “non-survivable” situation if it had not been for the exemplary handling by the flight deck crew. In my considered opinion this crew’s performance should be rated in the same category as the pilots who feature here and Sullenberger’s miraculous landing on the Hudson. Yet, it would have barely attracted attention if it had not been for the fact that a very popular Irish radio and TV presenter, Gay Byrne, had been among the passengers.

So I propose a “hurray” and a toast to all pilots whose experience, training and skills are successfully called upon to save the the people who entrusted their lives in their care.

Hear Hear! It is what they are trained to do, and they did very well.

You hear often about how automated these things are, that after pushing back from the gate in New York you just press the button labeled ‘Paris’ on the dashboard and the plane goes there – unless, and until, something goes wrong…

I have learned so much from FOL and Blancoliereo and Mentour Pilot that I have learned That Part 121 Operations or ATP Operations is very involved and never that simple. I think the general public are not as enthusiastic as to the nuts and bolts of flying. just get me from point A-to-point-b.

An aside:

Sylvia mentions that this particular aircraft has now been stored in Victorville, California. The incident as described here took place relatively recently, on 17th April 2018 in the New York area.

So it looks like a reasonable assumption that the aircraft had been repaired and returned to service. It does not seem reasonable to spend a lot of money to make a repair, even a patch-up in order to fly it across the USA to be mothballed. So it looks as if the aircraft has been retired about only a year after repair. It would seem to have been cheaper to scrap it there and then. So what exactly happened with it after this emergency?

The Wikipedia article says

The aircraft, N772SW, a Boeing 737-7H4 was subsequently flown to Boeing in Everett, WA on April 30, 2018 for repairs. The plane was moved into storage at Victorville, CA on June 7, 2018. The aircraft remains there and has not made a scheduled revenue flight since.

The description suggests that the only fatality was due to bad luck: a piece of cowling hitting a window rather than any more resilient part of the hull. An assessment at PHL may have concluded that the total damage was not large (e.g., no struts compromised) and that repairing the damage and returning the aircraft to service was economically reasonable, given that it was relatively new (hence more fuel-efficient). Boeing’s final-assembly plant may have found more damage and/or somebody at Southwest may have run additional numbers based on new projections based on the Trump economic bubble being likely to burst; a year later, the US Federal Reserve saw that the economy had softened enough (despite ridiculously high levels of deficit spending) that it started cutting interest rates.

I was surprised at first that the plane could be flown, but I can see that being able to replace an engine at any airport is a Good Thing given groundings for emergency inspection, bird strikes, etc.

Thanks for this. I wondered about it too.

That makes sense Chip. It also would confirm your observation that the aircraft was not severely damaged, otherwise an engine change alone might not have satisfied the FAA to allow the aircraft to be flown to Seattle.

An engine replacement in itself, assuming no major complications resulting from damage, can be accomplished in a surprisingly short time. An experienced team of engineering staff few could do it in a few hours.

Thanks for that info.

If you wanted me to, I could potter over to Victorville, it’s not that far away, and see what I could find.

Somehow I think they’d take a dim view of the likes of me rambling around with a camera, though. J.

Haha, I appreciate the offer, Jon!

spotterguide.net says the best view for the general public is from outside the fence. But I don’t know where this aircraft is, and if it’s even visible without chartering an overflight.

I’ve some thoughts re: Rudy’s comments on whether airline pilots can be considered heroes. We consider firefighters heroes when they do a dangerous job saving others, because they willingly go into dangerous situations they needn’t be in. A professional pilot isn’t on the plane to get from A to B: they’ve chosen to be there and care for the safety of their passengers. It’s not always apparent; when nothing goes wrong, commercial aviation is fairly safe nowadays. But incidents like this one remind us that it does take courage to commit to this job, and ability to rise up to its challenge when things go haywire.