In the cabin of Southwest flight 1380

Last week, we looked at Southwest Airlines flight 1380 which suffered an engine failure while climbing to cruise altitude on the 17th of April 2018. A fragment from the engine broke a cabin window, leading to a rapid depressurisation event. The crew immediately descended and diverted to Philadelphia, landing safely seventeen minutes after the engine failure took place.

There was one fatality, the passenger sitting in the window seat where the shrapnel struck the fuselage. This struck me as an incredibly tragic death. The flight crew and the cabin crew responded quickly and sensibly and yet, there was nothing they could do to save the life of the woman who happened to be in the wrong seat at the wrong time.

Although I covered the sequence of events in my previous post, I wanted to write about a secondary aspect of this flight, which hasn’t received much attention: the fact that the cabin crew ended up in an unsafe situation. During the emergency landing, the three cabin crew members sat down in the aisle, held down by seated passengers on either side.

The Boeing 737 was configured with 143 passenger seats, two flight crew seats, two cockpit observer seats and four flight attendant jumpseats on double retractable seat sets.. The forward cabin had two aft-facing seats and the aft cabin had two forward facing seats for cabin crew members.

There are six emergency exits: four floor-level door exits and two overwing window exits, serving 24 rows of passenger seats, where each row was two sets of three seats (ABC and DEF) except for row 11, which only had two passenger seats next to the overwing exit.

Southwest Airlines flight 1380 was a scheduled passenger flight from LaGuardia, New York to Dallas, Texas. There were two flight crew and three cabin crew on board.

Each cabin crew member was assigned a seat. Two were sat in the forward cabin, one at the forward entry door position, and the other at the forward galley door position. The third crew member was assigned the aft left galley door position. The cabin crew member at the forward entry door position was responsible for the forward cabin and had completed her training in 2016, two years before the accident. The crew member seated at the forward galley door position was expected to deal with both the front and aft cabins. She had completed her training in 2014. The third crew member, assigned to the aft cabin area, was a new hire and had completed her training just six weeks before the accident occurred.

There were 144 passengers on the flight that day. All 143 passenger seats were occupied and the 144th passenger, an SWA employee, was given the free jumpseat in the aft cabin. There was literally not a single seat free on the flight.

About half an hour after departure, the cabin crew heard a loud sound and the aircraft vibrated violently. The crew member assigned the forward entry door seat was in the forward lavatory and the other cabin crew member was in the cabin, near row 5. The cabin crew member assigned to the aft cabin was in the galley, preparing for the in-flight service. The first two cabin members immediately went to their assigned seats and put on oxygen masks. The newly qualified cabin crew member at the rear had not noticed that the oxygen masks had deployed until the SWA employee seated in the spare aft jumpseat alerted her to the situation. The cabin crew member then sat down at her station and put on the oxygen mask.

The airline’s flight attendant manual includes a four-step procedure that flight attendants are to follow in the case of an emergency decompression.

The first two steps, in order, were to “take oxygen from the nearest mask immediately” and “secure yourself.” The third step, which was to be accomplished by the flight attendant nearest to the forward control panel after the airplane reached a safe walking attitude, involved turning the cabin lights to bright and making the following PA announcement explaining the use of oxygen: “Ladies and gentlemen, pull down on the mask in front of you. Place the mask over your nose and mouth and breathe normally. The bag may not inflate. You are [emphasis in original] receiving oxygen. Fasten seatbelts and positively no smoking.” The last step was for flight attendants to don the nearest portable oxygen bottle, go through the aisle mask by mask to assist passengers in the cabin, and check the lavatories.

Both stations had portable oxygen bottles which the cabin crew then used to allow them to check on the passengers. The front cabin crew member noticed that some of the passengers were wearing the mask over their mouth only, rather than covering their nose and mouth. She ensured that all of the passengers were receiving oxygen and stopped at row 8 to help a female passenger with a child on her lap.

At the same time, the second cabin crew member stationed at the front continued along the aisle, telling passengers that they should breathe normally and reassuring them that they were receiving oxygen even if the oxygen bag did not inflate. Then she reached row 14, which is where the engine shrapnel had punched through the passenger window.

The passenger in seat 14A had been dragged out of the aircraft through the window while still buckled to her seat. The cabin crew member attempted to grab the passenger and got the attention of the cabin crew responsible for the forward area, who immediately had the passengers in seats 14B and 14C move out of the row, in case a bigger hole happened around the window.

The two cabin crew attempted to pull the passenger back into the aircraft, but were unable to. Two male passengers (in seats 8D and 13D) offered to help and they were able to drag the passenger back into the aircraft. They laid her down across seats ABC.

Meanwhile, the newly qualified cabin crew member seated in the aft position was also moving through the cabin to check on the passengers. She saw the other flight attendants and the two passengers with the injured woman.

The aircraft descended below 10,000 feet and in the cockpit, the flight crew removed their oxygen masks as they prepared for an emergency landing. It was clear that they had suffered severe damage of some sort and most likely a rapid decompression. Their focus was to get the aircraft safely on the ground but as soon as it was clear that they had the situation under control and were on an extended final approach, the first officer told the captain that he was going to contact the flight attendants to find out the status of the cabin.

The cabin crew member directed the other two passengers, who had been in 14B and 14C, to the aft galley. She heard the intercom chime and answered the phone. The first officer couldn’t hear her. You guys there? Hello? The cabin crew member could not hear anything over the noise in the cabin and hung up.

The first officer reported to the captain that there was no reply from the cabin.

A cabin crew member then made a cabin announcement asking for medical assistance from any qualified passenger. The passenger in 8D who had helped to pull the passenger back in was a paramedic and a passenger in the row ahead was a nurse. The two of them started CPR and the cabin crew member assigned to the front of the cabin retrieved the automated external defibrillator and the fast response kit for them to use.

Once the injured passenger was laid across the seat, and presumably the window blocked, the second cabin crew member (responsible for both front and aft cabins) who had discovered the situation moved to the aft galley to use the interphone to alert the flight crew.

Cabin Crew Member: Hey, we got a window open and somebody–somebody is out the window.

First Officer: OK

I’m not sure there’s anything much more he could have said to that.

First Officer: OK, we’re coming down. Is everyone else in their seats strapped in?

Cabin Crew Member: Yeah, everyone is still in their seats. We have people who’ve been helping her get in. I don’t know what her condition is but the window is completely out.

First Officer: OK. We’re going to slow down. (to the captain) Slow down to two hundred ten knots right now.

Cabin Crew Member: Are we almost there?

First Officer: Yes, we’re going to land as soon as we can.

Captain (to ATC): We’re going to need to slow down a bit.

Cabin Crew Member: OK, thank you.

The cabin crew member, who was still at the back of the cabin, then used the public address system to ask all passengers to remain seated, saying, “We are almost landing”. The other two cabin crew were still wearing their oxygen masks, having not realised that the aircraft had descended to a safe altitude, however they both confirmed that they heard the announcement that they were almost landing.

Originally, the captain had planned a long final approach to give them more time to go through checklists; however, when she heard about the injured passenger, she decided to expedite the approach.

The cabin crew member made another announcement: Everyone breathe and relax. Everybody breathe, we are almost landing. Everybody breathe, we are almost there.

The flight crew lowered the landing gear, which would have been a clear signal to the cabin crew that the aircraft was about to land.

The two cabin crew members assigned to seats at the front of the aircraft realised that they did not have time to return to their jumpseats for landing. One sat on the floor where she was, near row four or five, with the passengers in the aisle seats holding her down. The other went aft. However, there were no jumpseats available there: one seat was in use by the airline employee flying as a passenger and the other one, which had been assigned to the newly qualified cabin crew member responsible for the rear of the cabin, was now taken by one of the passengers who had been moved out of row 14. The two cabin crew members and the other passenger sat on the floor in the aft galley where, as much as possible, seated passengers attempted to hold them down.

First Officer: Your speed is good.

From the cabin: Heads down, stay down! Heads down, Stay down!

Electronic Voice: TOO LOW TERRAIN, TOO LOW TERRAIN

First Officer: Fifty feet. Thirty feet.

Electronic Voice: Ten.

The Boeing 737 touched down. The captain immediately exited the runway via a high-speed taxiway and stopped there, near a fire truck. She then used the public address system for an announcement.

Captain: Alright, ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain. The fire truck’s coming up on the captain’s side. Everyone remain seated and we’ll get everybody off as soon as possible. Thank you for cooperating and listen to your flight attendants.

The front cabin flight attendant called to ask if she should open the slide. “There is no smoke right now but we have a full window open, we’re doing compressions on someone.”

First Officer: OK, you just take care of the people, don’t get out yet.

Once it was clear that there were no signs of smoke or fire, the captain informed the rescue and firefighting personnel that they had an injury on board and went aft to check on the cabin.

The attendant who had been seated in the aisle near the front disarmed the forward galley door while asking passengers to keep the aisle clear for emergency personnel. The attendant responsible for the aft cabin disarmed the aft doors. The third attendant stayed with the injured passenger, who was given CPR by the two passenger volunteers until the emergency personnel boarded the aircraft. Then the passengers were evacuated via airstairs. Just over half an hour later, the flight crew were the last to leave the aircraft.

The badly injured passenger died in hospital shortly after arriving, with a cause of death of blunt force trauma of the head, neck, and torso. The injuries received in the initial moments of the depressurisation were considered not to have been survivable.

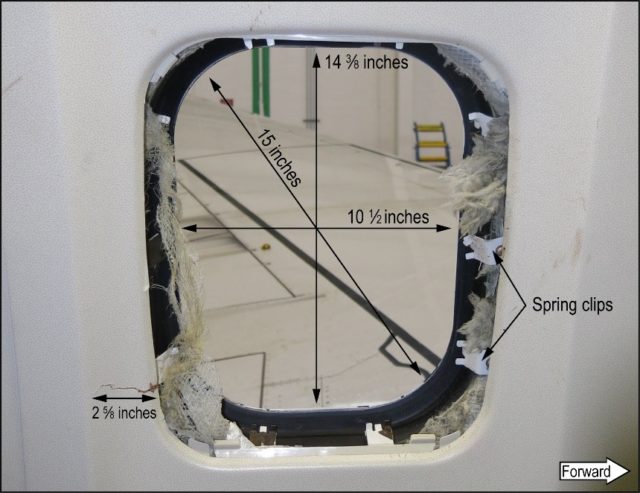

This was the first time that a Boeing 737 had lost a window. There have been 33 outer pane fractures (and 16 in the 757 fleet which uses the same passenger windows) but in every instance, the middle pane, which has a vent hole to release pressure and vent moisture, had remained intact. There was no guidance on how to deal with such a scenario.

The issue here is that the cabin crew members were not able to buckle themselves in for an emergency landing.

It’s clear that they were aware that the landing was imminent, both from the message from the first officer and the announcement that all three confirmed that they had understood. All three cabin crew could be heard on the CVR shouting the brace command (heads down, stay down), starting at about 19 seconds before landing. They were clearly aware that the aircraft was about to touch down but by then it was already too late.

All three flight attendants ended up on the floor and reliant on passengers to keep them in place. If it had been a hard landing, this would not have been enough. Additionally, the attendants were stationed in order to be able to disarm the doors and lead an evacuation of the aircraft as quickly as possible. If there had been a fire making an emergency evacuation necessary, then the fact that none of the cabin crew were at their positions at the emergency doors would have hindered the evacuation.

The airline’s Flight Attendant Manual talks about the need to administer first aid during an emergency landing.

…in a life-threatening medical situation during a routine landing, a Flight Attendant may be called on to administer first aid. The Flight Attendant might not be able to occupy the assigned jumpseat.

But the same section also states that during a planned emergency landing,

…the Flight Attendant must occupy the jumpseat.

This isn’t helpful and I suspect the implication is that the cabin crew might be in a passenger seat, rather than have no seat at all. In this case, the cabin crew weren’t administering first aid; it was two other passengers who were performing CPR.

The senior manager for in-flight training at Southwest Airlines University indicated the reasons that a flight attendant would not be in a jumpseat during landing. These reasons were (1) a flight attendant was providing first aid (in which case the two other flight attendants would be in their jumpseats); (2) a jumpseat was broken, or there was a hole in the fuselage near the assigned jumpseat (in which case the affected flight attendant would be secured in a passenger seat closest to his/her primary exit; and (3) a flight attendant was incapacitated and thus unable to perform required duties. The senior manager stated that “flight attendants need to be on their jumpseat” during landing because it is “the safest, most secure place for them” and because “they have to potentially be able to evacuate that aircraft.” The senior manager also stated that a passenger should not be reseated on a jumpseat instead of a working flight attendant.

At the same time, there are multiple references to reseating passengers, for example in the case of an air leak, as they had experienced on this flight, as well as lavatory fires, weight and balance requirements, accommodating passengers with disabilities, and moving a passenger out of an exit row if they would not be able to provide assistance during an evacuations. But nowhere in the manual does it explain what to do if there are no seats free for the passenger who needs reseating, other than the reference under first aid which states that the flight attendant might not be able to occupy the assigned jumpseat.

At no point does the manual give even the slightest hint what you are supposed to do about the passenger that you have put into your jumpseat when landing. I cannot really imagine a cabin crew member demanding that the passenger move to the floor for landing so that the flight attendant can have the jumpseat back.

The manual is clear that the passenger may need to be reseated but there’s simply no information as to what to do if there is no other seat for that passenger. No one seems happy to state outright that the passenger could end up without a seat at all. The presumption is clear: there must be a passenger seat available. But that’s an outdated assumption — airlines want every seat taken.

The report points out that the flight attendants should have considered the issue earlier:

This emergency situation involved an airplane with an unknown amount of damage and minimal contact with the flight crewmembers, who were busy controlling the airplane and performing other related tasks. As a result, once the injured passenger began receiving first aid from medically qualified passengers, the flight attendants should have focused on securing the cabin and themselves for the emergency landing and preparing themselves for the possibility of an evacuation. The NTSB concludes that, although not a factor in the outcome of this accident, the flight attendants should have been properly restrained in their assigned jumpseats in case an emergency evacuation after landing was necessary.

Now, I can see this as a valid argument for the cabin crew member assigned to the front of the cabin, who could and perhaps should have made her way to her jumpseat earlier instead of sitting down at aisle four or five. The second flight attendant who was using the intercom and the PA system at the aft galley also, perhaps, should have made sure she was at the front of the cabin earlier, in order to take her assigned seat. However, I find it a bit harsh that the issue of there being no jumpseats available in the back is given only a single paragraph in the final analysis of the report.

The accident flight was full, with no open cabin seats remaining, and the flight attendants needed to reseat the passengers in seats 14B and 14C so that the injured passenger (in seat 14A) could receive medical care. Both affected passengers went to the aft galley; one passenger sat on the flight attendant aft jumpseat, and the other sat on the floor. (The other aft jumpseat was occupied by an SWA company employee.) The SWA flight attendant manual included numerous references about reseating passengers but did not address a situation in which no additional seats were available. Postaccident interviews with SWA training personnel revealed that options for reseating passengers aboard a full flight had not been adequately considered as part of safety risk management. A review of FAA regulations, ACs, and Order 8900.1 (Flight Standards Information Management System) did not identify any specific guidance addressing options for reseating passengers when no additional passenger seats are available.

I find it a bit irksome that the cabin crew members themselves were blamed for not finding an answer to an issue that no one knew the answer to.

The NTSB report concludes with a recommendation that the FAA develop and issue guidance on how air carriers can mitigate hazards to passengers affected by an in-flight loss of seating capacity, which is clearly needed. They also recommend that Southwest Airlines include the lessons learned from this flight, emphasizing the importance of being secured in a jumpseat during emergency landings.

This implies that the cabin crew did not understand that it was important that they be seated and secured, without any reference to the fact that the aft jumpseats were taken, with one assigned to a staff member and the other by a passenger. Even if two cabin crew had made it to the front, there was simply nowhere for third cabin crew member and the remaining passenger to sit.

If the NTSB don’t know what the cabin crew should have done and Southwest Airlines do not know what cabin crew should have done and the FAA is tasked with finding solutions to this situation, how on earth can the report conclude that the cabin crew needed to be reminded of the importance of being in a jumpseat for landing?

I agree with Sylvia: the reports are excessively harsh in their criticism of the cabin crew.

The situation they found themselves in did require a certain amount of improvisation. Moving around in an aircraft cabin in a steep descent, whilst attending to the passengers – one of whom was seriously inured – would have challenged anyone. Even so in an aircraft with a window blown out, air rushing through the cabin, no doubt with the sudden decompression. In the suddenly less dense air fog would have formed, people would have suffered from ear pain.

The aircraft had been damaged, but no to any extent where controllability had been affected.

So in this situation, yes the cabin crew did break some rules and yes, in retrospect they might well have been able to handle the situation better.

But ultimately their first concern was the safety and well-being of their passengers and they deserve praise for their ultimate dedication.

They were the heroes (or heroines) in this story.

The cockpit crew: An engine failure – well within the remit of a trained crew. Structural damage: Resulting in a rapid decompression, again: a well-trained crew should be able to cope. Even with both occurring simultaneously.

The cockpit crew’s handling of the situation was excellent. Good crew coordination, the captain acted as a good commander should: she took the inputs from her first officer on board and as a result the situation was kept under full control. From what I read here, the first officer was more than just a back-up. His input was essential to the smooth handling of the situation. In other words: they did an excellent job. Does that elevate them to the hero status? I don’t see any reason to revise my earlier assessment: an first-class crew but NO, no heroes.

The cabin crew may not have handled the situation in a textbook manner, but still they did what they could under difficult circumstances.

Great analysis – as always. I agree the report seems harsh on the cabin crew.

I presume that with a window out the wind noise throughout the cabin is almost unbearable? This would make communication even more difficult.

As I understand it (from the paragraph starting “The two cabin crew members assigned to seats…”) 4 people were out of their seats on landing – all 3 cabin crew and one passenger. The injured passenger was taking up their seat and 2 other seats. So there were 2 empty and useable seats on landing. Perhaps a cabin announcement from the flight crew to say how close they were to landing would have focussed minds on finding seats for as many people as possible?

Yes, I agree, there were two seats free which could have been used if the cabin crew had moved forward more quickly. But the flight crew changed their minds in the final approach, deciding to simply get on the ground quickly rather than take their time and go over the checklists.

They clearly had difficulty hearing on the intercom (the first call, the first officer couldn’t hear the cabin crew member at all) and I wonder if this is why the impending landing wasn’t given another 60 seconds or so of warning.

Possibly that’s what the NTSB comment that you panned was about; if everyone had been perfectly focused the last passenger and one cabin attendant could have been buckled in instead of held down by passengers, even if two others were on the floor. (In theory those two might have buckled down in the cockpit, but that would have meant they would be available as quickly if there were any problems with landing; I expect there’s a rule somewhere that requires all of them to be in the cabin during takeoff and landing.) Or they could have meant that more passengers should have been in the floor and all the cabin crew buckled in, so that the people trained in dealing with trouble would be less likely to be hurt in a bad landing. (How the crew would have managed telling passengers to leave seats and get on the floor would be something an NTSB bureaucrat might regard as the responsibility of the airline’s PR staff.) Or whoever wrote that paragraph might not have read all of the report (or at least not read it well enough to do the arithmetic); I don’t know what the standards are for the people who write the reports. (A classic example of \nobody// reading what somebody else has written: a 1960’s Social Security manual contains a chapter of a science-fantasy novel that one of their employees was writing. He put it in just to prove nobody was reading what he wrote for the SSA.)

I wouldn’t think the noise of the window would be bad at approach speed and altitude, with the engine shut down — but the cabin crew would have been much more focused on keeping the passengers healthy than on hearing calls from the cockpit at a time when the cockpit crew should also be busy. If the NTSB wanted to be proactive instead of chiding, they might have recommended one-way very-short-range radios (driven from the cockpit, but broadcasting further back) and earpieces for the cabin crew, but I get the impression they’re wary of making recommendations that cost money in cases where spending the money wouldn’t have made an immediate difference.

Maidbloke, you are probably right. How much noise in the cabin is created by air rushing out through a broken window? I don’t know. In the case of my own experience with a rapid loss of pressurisation I remember a loud “bang” followed by a sharp hiss. The door seal had deflated very suddenly. When fully pressurised the cabin of any aircraft expands. In the Citation this causes a gap to open between the door and the door frame, which is taken up by an inflatable seal around the door. Wearing oxygen masks and headsets we had our hands full. Especially as the “horse-halter” type of oxygen mask that we had at the time depended on elastic straps to clutch it to the face. As it so turned out, the elastics were old and had lost a lot of their elasticity.

When they were renewed, we added a new item on the checklist: After flight, release the elastics and before flight: reset them in the quick-donning position. This prevented them from being kept in the stretched position all the time, e.g. when parked. Difficult to explain, but Citation 500 pilots will know what I mean.

Anyway, the cabin crew of flight 1380 did not seem to have had a lot of options, certainly limited under the conditions, and the manuals did not really fully cover the situation. Airlines are very pedantic and unforgiving when it comes to following the rule books. It can be argued that the crew were forced to do a little bit of improvisation, maybe a bit more than they should have under the pressure of an unusual emergency situation. The airline and NTSB should, in my considered opinion, have been a bit more forgiving. In the end result they did a good job.

One thing escapes me: during the final approach, just before touch-down the GPWS was calling out “Too low, terrain”. Once below 10.000 feet there was no longer any need to maintain a very high rate of descent. Except, maybe, in order to make a straight-in landing from a high altitude. But on very short finals, just about to touch-down the aircraft should have been in a stable situation with gear and flaps extended.

BTW: remember the 1990 BAC 1-11 incident where the cockpit window blew out? The captain was sucked out. Two cabin crew members held on to him as he quite literally dangled at the outside of the aircraft.

The first officer was on his own, virtually unable to communicate with all the noise around him hut he managed to keep the aircraft under control, made a safe landing and… the captain survived.

Now here is an example where a pilot handled a situation that was extremely far outside anything that he could have been trained for.

He was a hero !

I wondered about the too low terrain annunciations as well. I wondered if that might happen because they simply hadn’t set up for the alternative airport? I should go back and see if there’s any more about that — I noticed it in the context of the cabin crew (that it, it happened at the same time as they called the brace command) and was focused on other things.

Please don’t anyone laugh at me, but would it have been possible at all, in such an emergency situation, to use the toilets as seats? If it is plausible but they would not be super safe due to lack of seat belts, I wonder if an emergency seat belt could be added in the wall behind each toilet? Again, please don’t laugh. It just seems to me that sitting on the toilet (especially with a prior retrofitted seatbelt) would be safer than sitting on the aircraft floor with passengers attempting to hold down the personnel by putting hands on their shoulders.

I suspect they aren’t rated for safety and would not be any better than the floor (possibly worse, with the risk of things breaking apart trapping you in there) but I don’t really know. I’ll try to find out.

I also suspect that it would be a bad idea to have cabin crew on the wrong side of a door that should be latched for landing (so it doesn’t flap loose) and could be warped so as not to open after a bad landing. See also guess above about requiring cabin crew to be in the cabin.

Hi, I was thinking more about the two extra passengers from seats 14B and 14C, i.e. passenger could be belted in on the toilet. It is true though that this type of event – having passengers needing to be removed from their regular seats – does not happen very often at all. With cabin crew, you are right, there would be other factors to be considered.

It would probably be more useful to attach restraint harnesses to some of the rear cabin bulkheads for extreme emergency use only. These would be stowed in such a way that they would be unobtrusive, could be deployed by a sharp tug, and designed to be donned quickly. Perhaps the crew member would be restrained in a standing position so no fold-down would be needed.

Good idea.

Sylvia, the GPWS is autonomous so unless there was damage to the equipment, it should not have sounded. It seems to indicate that the crew, perhaps concentrating on a landing in the shortest possible time, were not on a proper glidepath. Strange, considering their miltary background and otherwise impeccable handling of the situation.

The aircraft had sustained damage. But mainly confined to the port engine and the window, leading to the tragic death of a passenger. But since the extent of the damage, less than perhaps initially suspected, was unknown to the crew until safely on the ground, the call “brace for impact” would have been conform to operational requirements. On the other hand it would appear that it did not really affect the handling of the aircraft, so why they came in so low over the fence that it triggered the GPWS is a bit of a mystery.

Modifiying an aircraft with all kinds of straps and safety belts to cater for each and every situation where people, cabin crew or passengers, can strap in the toilet or even against a bulkhead makes no sense.

Besides, the furnishing in a toilet can present a hazard by themselves, in case of a bad crash a person in a toilet can be worse off than in the cabin and besides, as Sylvia mentioned, the seat would not pass approval. With or without belts.