Germanwings 9525: Attempting to Understand

The mindset of the pilot whose suicide flight killed 150 people, crew and passengers, is hard to comprehend. He was the first officer and Pilot Flying of Germanwings flight 9525 and on the 24th of March 2015, he clearly and deliberately crashed an Airbus 320 into the French Alps, killing everyone on board.

The Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses (BEA) were responsible for the accident investigation as the crash happened on French soil. They took almost a full year but the 110-page report came out this week.

In order to make any sense of what happened that day, we need to go back seven years, to the first officer’s original decision to become a pilot.

The first officer took entry selection courses with Lufthansa Flight Training in 2008 along with 6,530 other applicants. He was one of only 384 selected. The evaluations included mental ability, logical reasoning, interpersonal skills and personality traits.

Once selected, he needed to apply for a class one medical certificate, which he received in April. He started his basic training at Lufthansa Flight Training Pilot School in Bremen in September. However, he suffered from a severe depressive episode which started that August and in November, just two months after starting, he had to suspend his training for medical reasons.

His medical certificate was not revalidated in April 2009 when it was due. On the 14th of July he requested the renewal again along with a report from his treating psychiatrist which stated that the pilot was entirely healthy and that the treatment had ended. The renewal was refused by the Lufthansa aeromedical centre.

On the 28th of July in 2009, the medical certificate was revalidated but this time included included a waiver which said that the certificate was invalid if the pilot suffered a relapse into depression.

In August 2009 he restarted his training with no further issues.

In 2010, he applied for an FAA third-class medical certificate which would allow him to fly light aircraft in the US. He was initially told that he was not eligible because of his history of reactive depression. He submitted the translated reports from the treating psychiatrist and psychotherapist previously submitted to Lufthansa Flight Training, which stated that the treatment was concluded and that the patient’s high motivation and active participation contributed to the successful completion of the treatment.

In July 2010 he was issued an FAA third-class medical certificate. A letter accompanying the certificate stated that, because of the history of reactive depression, “operation of aircraft is prohibited at any time new

symptoms or adverse changes occur or any time medication and/or treatment is required”.

He completed his training with Lufthansa Flight Training in 2013 when he took and passed his A320 type rating. During his training and recurrent checks, his instructors and examiners considered his professional level to be above average. He joined Germanwings on the 4th of December 2013.

The cost of the full curriculum at Lufthansa Flight Training is about €150,000, of which €60,000 is funded by the student. The pilot took out a loan of €41,000 in order to help him finance his training.

Once he started work at Germanwings, he was covered by the Lufthansa Group’s Loss of Licence insurance. However, for the first five years of employment, this insurance only offered a one-time payment of €58,799 if he became permanently unfit to fly.

His medical certificate was revalidated or renewed every year after it was revalidated in 2009, with the most recent being in the summer of 2014. Each time the certificate included a note which said, Note the special conditions/restrictions of the waiver FRA 091/09-REV-. The Aero-Medical Examiners (AME) who examined him also included a psychological fitness and had no concerns regarding any moods or behavioural disorders which would have required future psychiatric evaluation.

In December of 2014, a year after starting work at Germanwings, the pilot began to show symptoms of a psychotic depressive episode. He consulted several doctors and a psychiatrist and was prescribed anti-depressant medication. He mentioned in an email around the same time that he wasn’t able to get additional loss-of-licence insurance because of the waiver on his medical certificate.

The regulations require that the licence holder (that is, the pilot) should seek aero-medical advice as soon as he starts a course of prescribed medication which may interfere with his duties. The prescription of the antidepressant medication invalidated his medical certificate, but the pilot neither reported the situation nor sought an appointment with Aero-Medical Examiners (AME) who would have been aware of the restrictions.

In February 2015, the pilot was diagnosed with a psychosomatic disorder and an anxiety disorder. On the 10th of March, a fortnight before the crash, the same physician diagnosed a possible psychosis and referred his patient for psychiatric hospital treatment.

At the same time, a psychiatrist prescribed anti-depressant and sleeping aid medication. Neither the physician nor the psychiatrist informed any aviation authority although both issued several sick leave certificates and they were presumably aware that he was unfit to fly. Most medications used to treat depression are medically disqualifying for pilots in most countries, although Australia and Canada are notable exceptions. In Europe, no certification will be considered while using psychoactive drugs such as the medication prescribed to the pilot.

In 2004, the Aerospace Medical Association argued that absolute prohibitions against pilots flying while taking anti-depressants would be reconsidered, based on evidence that professional pilots were refusing medication and continuing to fly without treatment. They collated data based on pilots who had contacted the Aviation Medicine Advisory Service (AMAS), a US-based providor of aeromedical advice for pilots. AMAS had received 1,200 telephone inquiries from pilots who had been diagnosed as having clinical depression and had been advised to take anti-depressant medications. Of the 1,200 pilots, 60% said they planned to refuse medication and continue to fly. 15% planned to take the medication and continue to fly, without informing the FAA. Only 25% planned to take sick-leave to undergo treatment and return to work when aeromedically cleared to do so.

The pilot was obliged to report his diagnosis and the medication prescribed. However, the risk of losing his medical certificate and thus his right to fly as a professional pilot was a powerful motivator to keep it quiet.

Physicians around the world have a legal responsibility to report patient information if there is a risk to the public. In the UK, reports from treating physicians and psychiatrists are required by the UK CAA for any pilot with a history of depression.

However, the Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses found that, specifically in Germany, where breaking medical confidentiality is a criminal offence, the regulations were not clear on when the threat to public safety outweighed the requirements of medical confidentiality. Violation of medical confidentiality has penal consequences in the German criminal code.

If a holder of a medical certificate contacts his family doctor or another physician, who detects an illness not compatible with the pilot duties or with flight safety, the contacted physician is not obliged to inform the responsible AME nor the employer nor the aviation authority. Due to medical confidentiality reasons, the information of third parties is impeded. The possibility to disclose aeromedical data depends upon the imminent danger resulting from the illness of the pilot concerned. Nevertheless the principle of confidentiality can prevent the treating doctor from disclosing such information.

The report goes into a lot of detail regarding this and my explanation is greatly oversimplified but the crux of the issue is that there is a conflict between the German data protection laws (which take precedence) and the EU regulations as to whether a family doctor must report the situation if a commercial pilot is unfit to fly. In Germany, the fact that he is unfit to fly does not oblige the physician to report him.

There are explicit exceptions for imminent danger and threat to public safety; however those phrases are not formally defined. The doctors treating the pilot would have had to predict that there was imminent danger and they would have been at risk of a year in prison if they were found to have exaggerated the danger.

It’s also worth noting that the pilots or instructors who flew with the pilot in the months before the accident had no concerns about his attitude or behaviour during the flights. He did not appear to be a danger.

However, it is now clear that on the 24th of March 2015, the pilot was suffering from a psychiatric disorder, possibly a psychotic depressive episode, and was taking psychotropic medication which made him unfit to fly.

That morning, the crew met at Düsseldorf at 06:01 UTC and flew the Germanwings Airbus A320-211 registration D-AIPX to Barcelona, where they landed at 07:57

The flight data recorder had 39 Mb of data, including the data from the morning flight from Düsseldorf to Barcelona. The investigators found disturbing data relating to the earlier flight.

07:19:59 The aircraft was cruising at FL370 (37,000 feet). The cockpit door opened and then closed as the captain left the cockpit.

07:20:29 Air traffic control asked the flight to descend to FL350 (35,000 feet). The co-pilot correctly read back the instruction.

07:20:32 The altitude was set to FL350 and the aircraft was put into a descent.

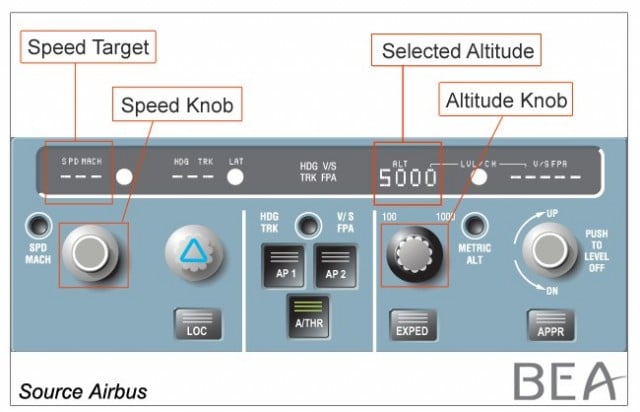

07:20:50 The selected altitude was decreased to 100 feet. It was then increased to 49,000 feet and then to 35,000 feet.

07:21:10 Air traffic control instructed the crew to continue the descent to FL210 (21,000 feet).

07:21:16 The selected altitude was 21,000 feet.

07:22:27 The selected altitude was set to 100 feet.

07:24:13 The selected altitude was changed several times but then set back to 25,000 feet.

07:24:15 The buzzer sounded to request access to the cockpit.

07:24:29 The cockpit door was unlocked and opened, corresponding to the return of the captain.

07:25:32 The flight crew was instructed to descend to FL170 (17,000 feet).

07:26:16 The altitude was selected and the descent began. The flight continued normally.

Because the autopilot was engaged, the changes in selected altitudes did not influence the aircraft’s descent path. It seems clear in retrospect that this was a practice run.

At 09:00, the same crew departed Barcelona on the same Airbus 320 for the commercial passenger flight Germanwings flight GWI18G with six crew and 144 passengers on board. They departed late. The first officer was the Pilot Flying.

The autopilot was engaged in CLIMB and NAV mode. During the climb, the buzzer sounded to request access to the cockpit. The two pilots and a cabin crew member had a conversation about the stop at Barcelona. The cabin crew member left the cabin a few minutes later.

The flight crew discussed the delay at Barcelona. The aircraft levelled off at cruise altitude of 38,000 feet and the flight crew contacted Marseille en-route control centre.

At 9:30, the captain, in his role as Pilot Monitoring, read back the air traffic controller’s clearance for the flight to proceed direct to the IRMAR waypoint.

That was the last that air traffic control heard from the flight.

After the call, the captain asked the first officer to take over communications, as he was leaving the cockpit. The heading changed consistent with routing towards IRMAR and the captain left the cockpit.

It was 09:30:53, just seconds after the captain left the cockpit, when the selected altitude was changed from 38,000 feet to 100 feet, the minimum value that it is possible to select on the A320. The autopilot changed mode to open descent and autothrust changed mode to thrust idle. The aircraft began its descent and both engines’ speed decreased.

Two minutes later, the speed management changed modes from managed to selected. This means that the crew selects the targets speed rather than the flight management system automatically determining the speed.

The aircraft was travelling at 273 knots. The selected target speed was 308 knots and the speed began to increase. The descent rate varied between 1,700 feet per minute and 5,000 feet per minute.

The selected speed was changed six times, initially down to 288 knots and then stabilising was 302 knots.

Air traffic control asked the flight crew what cruise level they were clear for. This was obviously in response to the fact that the aircraft was now at 30,000 feet and descending. The controller called twice more but received no response.

At 09:34:23, the selected speed was increased to 323 knots. The buzzer sounded to request access to the cockpit. The controller tried again to contact the flight.

At 09:34:47 Marseille control centre tried to contact the flight crew on their previous frequency. They called twice but received no response. The aircraft was at 25,000 feet and descending.

The selected speed was increased to 350 knots. This is the maximum operating speed of the Airbus 320 and the highest setting that the flight crew can select.

The aircraft descended at 345-350 knots with the autopilot and autothrust engaged. The cockpit call signal from the cabin sounded four times but was not responded to.

The CVR recorded knocking sounds on the cockpit door and muffled voices, including a request for the door to be opened.

Marseille control centre attempted to contact the flight three times on the emergency frequency and twice more on the frequency where they were last in contact, with no response.

An air traffic controller from French Air Defence tried to contact the flight crew on three occasions on the emergency frequency, with no response.

At 09:39:30 the sound of violent blows on the cockpit door can be heard. These continue for over three minutes but the reinforced door held firm.

The first officer’s side stick moved but with “low amplitude inputs”, gentle enough movements that the autopilot remained engaged.

Another aircraft attempted to contact the flight crew with no response.

At 09:40:41, the Ground Proximity Warning System (GPWS) triggered with an aural warning: TERRAIN, TERRAIN, PULL UP, PULL UP. These warnings continued until the end of the flight.

At 09:41:06 the cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorder failed as the aircraft crashed into the side of the mountain at 1,550 metres (5,085 feet) above sea level. The wreckage was spread over an area of four hectares (10 acres).

3.2 Causes

The collision with the ground was due to the deliberate and planned action of the co-pilot who decided to commit suicide while alone in the cockpit. The process for medical certification of pilots, in particular self-reporting in case of decrease in medical fitness between two periodic medical evaluations, did not succeed in preventing the co-pilot, who was experiencing mental disorder with psychotic symptoms, from exercising the privilege of his licence.

The following factors may have contributed to the failure of this principle:

- the co-pilot’s probable fear of losing his ability to fly as a professional pilot if he had reported his decrease in medical fitness to an AME;

- the potential financial consequences generated by the lack of specific insurance covering the risks of loss of income in case of unfitness to fly;

- the lack of clear guidelines in German regulations on when a threat to public safety outweighs the requirements of medical confidentiality.

Security requirements led to cockpit doors designed to resist forcible intrusion by unauthorized persons. This made it impossible to enter the flight compartment before the aircraft impacted the terrain in the French Alps.

I’m painfully aware that I’ve not discussed the cockpit doors and issues of cockpit security, along with a number of other issues highlighted by the report. I may do a follow-up post for some of the other issues (please let me know in the comments if you are interested in this) but for the initial post, I took the decision to highlight what I think were the most important lessons learned from this tragic event.

The full report is available in French, German and English here: Accident to the Airbus A320-211, registered D-AIPX and operated by Germanwings, flight GWI18G, on 03/24/15 at Prads-Haute-Bléone

It concludes with recommendations for further action dealing with medical evaluations for pilots and the reporting thereof, as well as better mitigation of the consequences of loss of licence for commercial pilots.

These, I believe, are the key factors which need more attention.

Chilling. And a bit strange to think that considerations of confidentiality about a pilot’s medical fitness to exercise the privileges of his licence were a contributory, if not a direct factor in this very sad accident.

In my days I was involved in a pilot losing his licence for medical reasons. He had invoked confidentiality after an unexplained medical incident which, had it occurred in the air, would nearly certainly have resulted in a crash as it happened less than an hour before he was due to fly a group of people on a single-crew operation. His lack of cooperation forced my hand; I felt that I had no option but to ground him. Eventually, he lost his licence and never spoke to me again.

When I had to stop flying, it took me a long time to get used to being grounded. I suppose annoying all of you here by writing comments in Sylvia’s excellent website is some kind of therapy.

Flying is the life of a professional pilot, in the most literal sense.

Otherwise, can you imagine anyone other than a mad person, landing at a major airport, rushing to a nearby grass aerodrome and donning a flight suit, helmet and goggles to rent an old 1934 Tiger Moth or Stampe biplane and go for a half hour aerobatics, then rushing back to the airport to continue flying IFR? I bet Sylvia can – and would do the same thing if she had the chance.

Fortunately, it is virtually unthinkable that any pilot, facing the sudden and untimely end of his or her career, would commit suicide by flying an airliner full of passengers into a mountain. And besides, procedures have been put in place to reduce that .chance to as close to zero as possible.

Rudy, people come to my website specifically for your comments! Take a look at http://fearoflanding.com/accidents/accident-reports/reconsidering-the-cause-of-twa-flight-800/#comment-1475780

So please don’t stop. :)

It’s not a proper Fear of Landing blog post until it has a comment from Rudy :-D

Back on topic, that “practice” altitude change is chilling to read.

I have a client business which deals with reward and recognition gifts for company employees worldwide, they have thousands of clients and we get employee data coming in from all over the world to import into our system. Germany is the only country where the employee name in the incoming data we get is replaced with “Emplyee nnnn” with a tracking number. The Germans take their privacy VERY seriously indeed.

As a pilot and clinical psychologist practicing in the US, I have been following this case very carefully. I suspect that some of what I will say is unpopular, but I’d like to put it in the context of this being an extremely rare event. In searching the US NTSB database, I could find only a handful of incidents of pilot suicide by airplane. All of them were solo pilot operations in small GA aircraft.

I believe strongly that routine invasions of privacy and reporting requirements may actually do more harm than good. There is a terrible stigma in seeking help for emotional struggles, and I think it’s worse among pilots as they fear the impact on medical certificates. But, I believe it to be far better that a person seek treatment. Pilots are as human as anyone, and this coupled with the stress, family strain, and perhaps difficult financial situations increase the chances that emotional distress will be experienced. Setting up a system (or worsening a system) so that seeking help is punished is a very bad situation. It won’t prevent this from happening again.

Instead, I think we need a threat management strategy that involves better intelligence about those who may be at risk. This would encourage fellow crew members, co-workers, family and friends to take potential concerns seriously. Education about what to look for and how to intervene has a better chance of catching the person in acute distress. It should be noted that the proposals on the table fall on the untenable assumption that a person who is a risk will have seen a physician or psychologist.

I don’t think you’ll find it that unpopular. I think the aviation industry has learned that a knee-jerk reaction to a rare occurrence usually causes more problems in the long run. There has been a lot of improvement on making it easier for pilots to seek help: not just for depression but also for addictions, alcoholism and other issues. However, at the same time, the medical certificate has meaning and I don’t think we can quietly pretend that a pilot is not in a dangerous state (including stress and fatigue). The problem is, that there are circumstances in which a pilot is not trusted to be in control of the welfare of a commercial passenger flight. The drugs that had been prescribed to the pilot were considered to be not compatible with operating an aircraft. Note that a lot of progress has been made to avoid blanket bans (whether or not his license was at risk for treatment of psychological issues was based on the drugs he was prescribed) and to give pilots opportunities to maintain their medical certificate or regain it which in the past was more difficult.

The answer is of course not to punish pilots who seek help but in many cases, the risk of not being allowed to fly is the worst punishment of all; and that’s hard to mitigate. In this case, that was compounded by the amount of debt the pilot had incurred in order to get his commercial license: the airline had protections in place so that a pilot who can no longer fly receives financial support, but it was not even enough to pay for his training, let alone set him up for a new job somewhere else.

If you ever learn about the crash on Air Crash Investigation, it becomes even more disturbing. It may just be actors and CGI, but when you watch the episode, you can see the captain’s desperation to get in and the passengers attention to the noise. You can see the fear in their eyes when they realize they are going to die. It’s one of the few episodes where I have cried.