Fatal Crash of Blue Angel 6: Military Investigation Released

Yesterday, the United States Department of the Navy released its investigation into the crash of Blue Angel Number 6.

The accident occurred on the 2nd of June 2016 during the U.S. Navy Flight Demonstration Team, The Blue Angels demonstration at the Great Tennessee Air show at Smyrna, Tennessee. The pilot, Captain Jeffery M. Kuss, USMC, was the sole pilot of the Naval Flight Demonstration Squadron (NFDS) F/A-18C BUNO 163455 (FA/18C Hornet) as Blue Angel 6. He had no previous military mishaps or flight violations.

This video shows the manoeuvre going wrong shortly after take-off:

At around the 25 second mark, Blue Angel 6 can be seen climbing steeply with a barrel roll at the 35 second mark. The video pans away as Blue Angel Six enters into an uncontrolled descent around the 40 second mark. At the one minute mark, the camera returns to focus on the black fireball.

That morning, Blue Angels 1 through 6 departed Pensacola, Florida as a formation, overflew downtown Nashville, Tennessee and arrived at Smyrna Airport at about 10:00 local time.

An hour later, Blue Angels 1-4 (the Diamond Formation) and Blue Angels 5-6 (the Solos) flew separate circle flights over the airfield. Circle flights allow the Blue Angel pilots to become familiar with the airshow airspace, obstacles, terrain, and specific checkpoints before the show. They also use Google Earth images in order to identify checkpoints, show lines and obstacles in a five-mile radius.

After completing their circle flights, Blue Angel 5 and Blue Angel 6 took part in a photo shoot. The Blue Angels then met up again to brief the afternoon practice show. At the briefing, there were no concerns about the show site, terrain, obstacles or weather. As the weather was good, they briefed for the “high show” which requires a ceiling of 9,000 feet or greater. There were some scattered clouds at 3,000 feet which weren’t considered an issue.

After the brief, the Blue Angels went to the Water Wagon, which is where the pilots review their individual Aircraft Discrepancy Books and sign an “Aircraft Acceptance A sheet” (in addition to getting drinking water). Noteable is that Blue Angel 6 did not sign his sheet on this occasion. No one appears to have noticed at the time.

They began their practice at 14:45 with the Take-Off Checks. Blue Angel 1 (flight lead) calls for the altimeters to be set to 0, so that all six Blue Angel aircraft have the field elevation set at 0 for the reference during flight. The aircraft have two altimeters: barometric and radar. By setting the altimeter to zero, the pilots’ barometric altimeters will shows the height above ground level (rather than the height above mean sea level). I’m not sure why the report says that both should be set to zero, as the radar altimeter constantly measures the actual altitude above the terrain, as opposed to a barometric altimeter which provides the distance above a defined point (mean sea level or the airfield). It would already be set to zero.

The radar altimeter is ineffective when the aircraft has extremely high and low nose angles, which is why the barometric altimeter is used for specific manoeuvres such as the High Performance Climb. The radar altimeter is used in other manoeuvres for better precision. The pilot selects the radar altimeter using the ALT switch on the Heads-Up Display (HUD) control panel.

Billowing clouds passed over the departure end of the take-off runways (Runway 14 and 32). Blue Angels 1-4 (Diamond Formation) agreed to perform a Diamond Burner Go instead of the High Show Take-off manoeuvre, worried that the cloud might impact the manoeuvre. As they taxied for Runway 32 for their departure, Blue Angel 6 asked Blue Angel 5 about the clouds over Runway 14 and whether the High Performance Climb would be possible with the clouds near the projected flight path. Blue Angel 5 said that he thought Blue Angel 6 could successfully make the manoeuvre.

The Solos proceeded to Runway 14. At 15:01:23, Blue Angel 5 and 6 made their timing call of “Ready, Hit It!”.

Blue Angel 5’s initial manoeuvre was the Dirty Roll on Take-off. Blue Angel 6 had a set of manoeuvres: Low Transition followed by High Performance Climb followed by the Split S. Blue Angel Six reached 312 knots calibrated airspeed (KCAS) and pulled the backstick back by 4.9 inches for 5.72 G’s. With his nose up at 60.2°, he entered the High Performance Climb.

Blue Angels 5 and 6 use the Solo SOP (Standard Operating Procedure). The Low Transition and initial portion of the High Performance Climb complied with the Blue Angel SOP. However, Blue Angel 6 then began the Split S before he reached the mandatory minimum altitude of 3,500 feet above ground level, possibly because he was still concerned about the clouds at the end of the runway.

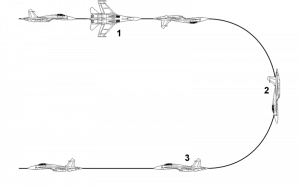

The Split S was a dog-fighting manoeuvre first used during World War II to disengage from combat. To execute a Split S, you half roll your aircraft inverted and then execute a descending half-loop, which leads you to flying level in the exact opposite direction at a lower altitude.

The initial reason for the half-roll at the beginning, by the way, was because the British fighters used Merlin engines with carburettors which would stall under negative g-force. The German fighters didn’t have the issue, because their engines used fuel injection. Their original manoeuvre was a Split S without a half-roll at the start.

The Blue Engine Solo SOP states that the pilot should select the barometric altimeter during the High Performance Climb and attain an optimum airspeed of 125-135 knots and a minimum altitude of 3,500 feet above ground level on the barometric altimeter before starting the 180° roll to inverted at the top of the climb. Once inverted and level, the pilot ensures that he can “make a safe bottom” which I assume means that he has the height required for the manoeuvre. Flying 90° nose low, the pilot monitors the G, deselects the afterburner, reselects the radar altimeter and transmits “Vertical, Blowers, RadAlt” to confirm that he’s now vertical and has set up the aircraft correctly. The pilot also visually seeks out the Diamond to ensure that there’s no conflict.

The airspeed during the descent into the Split S should be 250-300 knots calibrated airspeed (KCAS) and then once at the bottom of the descent, accelerate to 400 knots for the clear. The SOP says that 4 Gs should not have to be exceeded in order to make the bottom of the Split S, with 150 feet above ground level being the minimum altitude. Afterburners can be used, if necessary, for airspeed corrections.

The Dive recovery rules that you must have a pitch angle of 60° for 2,000 feet, 45° for 1,500 feet, 20° for 1,000 feet, with 3,000 feet above ground level as the minimum altitude for 90° nose low. 3,000 feet above ground level is also the minimum altitude for airspeeds between 300-350 knots. Airspeeds above 350 knots require the pilot to start the Split-S at a higher altitude. The dive recovery rules must be committed to memory and used to ensure that a safe recovery can be made during the manoeuvre, first and foremost

The following is in the Solo SOP in bold: maximum performance dive recovery manoeuvre is required any time one of the above conditions is met to ensure terrain avoidance.

Any variance in airspeed, high density altitude, terrain or pilot proficiency would require the minimum altitudes to be significantly increased. The pilot was proficient and there was no unexpected issue with high density altitude or terrain. That leaves the airspeed as a critical factor.

Smyrna Airport doesn’t have its own radar, so radar coverage was provided by Nashville Air Traffic Control. The secondary radar usually picks up aircraft departing Smyrna Airport at approximately 1,000 feet, as long as the aircraft has its transponder set. Blue Angels 1, 5 and 6 were given preassigned radar squawk codes. However, after take off, only Blue Angel 1 and Blue Angel 5 appeared on the Nashville ATC radar. There was no sign of Blue Angel 6. He never set his transponder with the squawk.

Again, no one appears to have noticed this as odd until after the accident.

Anyway, Blue Angel 6 executed the High Performance Climb, flying at over 184 knots just before reaching 3,196 feet above ground level on the barometric altimeter. The SOP required 3,500 feet and the optimum airspeed for entering the manoeuvre was cited as 125-135 knots. He was too low and too fast.

Instead of executing a 180° roll to inverted as the transition from the High Performance Climb to the Split S, Blue Angel 6 executed a 540° roll, that is, he rolled one and a half times to end up inverted instead of just half a roll.

A 540° roll is not an approved manoeuvre; however, there was no particular issue caused by this deviation from the SOP. The problem was that Blue Angel 6 started the manoeuvre too low. As he descended from 3,196 feet (peak altitude) to 2,856 feet above ground level, the aircraft was nose down at an angle of 86.8° and travelling at approximately 238 knots; the SOP says between 250-300 knots for the descent.

Blue Angel 6 made his radio call, “Vertical, Blowers, RadAlt,” to confirm 90° nose down, throttles retarded from MAX and switched to radar altimeter.

However, he did not retard the throttles. They remained at MAX.

At 15:01:45.9, the aircraft was pitched 33.6° nose down at 1,960 barometric feet above the ground / 1,568 radar altimeter feet above the ground, pulling 3.73 Gs and travelling at 268 knots. This was in line with the dive recovery SOP of a minimum of 60° at 2,000 feet.

Note: the difference between the barometric altimeter and the radar altimeter was because the terrain to the southeast of the airfield was higher than the airfield by 392 feet. The radar altimeter correctly always shows the distance to the ground while the barometric altimeter is showing the distance to the airfield elevation.

At this point, the aircraft was at full power and descending at a rate of 21,000 foot per minute.

One second later, Blue Angel 6 was pitched 23.8° nose down at 1,472 radar altimeter feet above the ground, pulling 3.48 G’s and travelling at 268 knots; still in line with the dive recovery SOP of 45° nose down for 1,500 feet.

But the aircraft was still descending way too fast, at 17,280 foot per minute. That’s 288 feet per second. The dive recovery limits don’t factor in the rate of descent. It’s possible that Blue Angel 6 believed that everything was fine as he descended through these levels because his pitch and altitude were correct, even though his throttles were at max power and he was speeding towards the ground.

Another second passed. The aircraft was 12.6° nose down at 480 radar altimeter feet above ground level, 3.48 G’s and 272 knots. Technically, this was still in line with the SOP recovery minimums of 20° nose down for 1,000 feet… except for the massive rate of descent less than 500 feet from the ground.

At this point, the disparity between the barometric and radar altimeters was 688 feet; the barometric altitude was 1,168 feet.

Two seconds later, Blue Angel 6 was at 2.8° nose up just 96 radar altimeter feet above the ground, pulling 3.11 Gs and travelling at 264 knots. Even if the pilot was looking at the barometric altimeter setting of 456 feet, he was clearly much too low for this manoeuvre. Beyond this, the Split S is a visual manoeuvre with reference to outside, especially when it comes to rate of descent. He should have seen how fast that he was descending, even though the aircraft nose was now pitched up. However, he never attempted any sort of dive recovery.

At just 96 feet over the ground, he was still descending at 5,760 feet per minute.

Just prior to Blue Angel 6 impacting the ground, the Blue Angel Flight Surgeon, acting as a safety observer and evaluator at the Communications Cart, radios, “Kooch check alt,” to prompt Blue Angel 6 to check his altitude.

It is mathematically impossible to successfully execute a Split S (radius of turn in the vertical) manoeuvre under the parameters that Capt Kuss flew. The circumstances required pilot recognition of the situation in a rapidly dwindling window for recovery.

It was only at this late stage that the stick moved forward, indicating that Blue Angel 6 had removed his hand from the stick and reached for the ejection handle.

After the pilot pulls the ejection seat handle, there’s a 0.3 second delay to allow the canopy to be jettison. Then another 0.2 seconds later, the catapult fires. At a total elapsed time of 0.8 seconds from the ejection handle being pulled, the drogue shoot fires to stabilise and decelerate the seat. At 1.8 seconds total elapsed time, the seat/man separation begins. The ejection sequence is complete at two seconds total elapsed time from the moment that the pilot initiates it.

One second after Blue Angel 6 initiated the ejection sequence, the last data from the aircraft was recorded, with a pitch of 7° nose down and a radar altimeter reading of 0 feet above the ground, 1.86 G’s and 48 knots.

The aircraft flew into a grove of trees. The ejector seat propelled the pilot out of the aircraft but the ejection sequence never completed.

The pilot and the seat never decelerated and never separated as they crashed into the trees. The aircraft travelled a further 80 feet before it impacted the ground. The impact sparked an explosion which instantaneously burned the parachute and the drogue shoot. The aircraft was completely destroyed in the explosion.

Captain Kuss died of blunt force trauma injuries.

The Communications Cart saw the fireball from the impact and transmitted “Knock it off” over the radio. The phrase Knock it off directs all aircraft to cease manoeuvres. The command was acknowledged immediately by Blue Angels 1 through 5.

Blue Angel 5, the other solo flight, circled the accident site at 2,000 feet. Blue Angel 3 and 4 detached from the Diamond and landed at Runway 14. It was 15:05, just four minutes from their initial take-off.

Blue Angel 1, the flight lead and Commanding Officer, circled the accident site at 2,500 feet above ground level while Blue Angel 2 circled at 3,000 feet. Blue Angel Five continued to circle at 2,000 feet. One can only imagine what was going through their minds.

At 15:08 Blue Angel 2 detached and landed on Runway 14. Two minutes later, Blue Angel 5 detached and landed on Runway 14. The rescue helicopters departed Smyrna Airport for the accident site and after they departed, Blue Angel 1 landed on Runway 14.

The investigation cites the probable cause as “pilot error” and there’s no question that Blue Angel 6 started the manoeuvre too low and too fast. He didn’t reduce his power in the descent and accelerated towards the ground. Finally, he didn’t attempt any recovery from the manoeuvre even though he was falling from the sky at great speed. He did attempt to eject but it was much too late. In the end, it comes down to him.

Although Capt Kuss was a highly trained and respected naval aviator, his deviations from standard operating procedures in executing the Split S maneuver resulted in a fatal loss of situational awareness.

But of course it’s not that simple. All the headlines seem to cite Pilot Error; however, the report detailed a number of different issues which, in a civilian report, may well have been considered contributing causes.

The investigation found that the Standard Operating Procedures did not offer the team the safety that they should. Here’s a damning statement from the report, where NFDS stands for Naval Flight Demonstration Squadron, in other words, the Blue Angels.

The Blue Angel SOPs are some of the most important documents that exist within the NFDS. They are essential for turnover, training, standardization, safety, and the effective execution of Blue Angel flight demonstrations. They contain years of experience and knowledge that is passed down to team members assuming new positions as well as new Squadron members assuming the positions for the first time. Portions of the SOPs have been “written in blood,” but even with this level of importance, the Blue Angel SOPs and the SOP support processes need improvement. Currently, the NFDS adheres to standard Navy archival protocol, meaning that SOPs are kept up to five years, or until superseded. It is standard practice for the Blue Angels to update (supersede) their SOPs every year. Because there is no archival system in place, the “who, what, where, when, and why” that initiated a change/modification/addition is lost. Case in point, the NFDS has no idea when, who, or why the Split S Solo Dive Recovery procedures were incorporated into the Solo SOP. They do not comply with the F/A-18 Performance Manual Dive Recovery charts.

The content of the NFDS Solo SOP Low Transition/High Performance Climb/Split S requires revision. The maneuver description is vague and poorly written. The maneuver description does not provide detailed standards for execution under varying conditions. Quantifiable limitations and additional safety factors must be added. “No maneuver” conditions must be amplified and articulated with additional granularity.

The requirement for version control sounds petty; however, when the investigators requested the most current version of the SOPs, the Blue Angels provided multiple different versions of the SOPs and none of them was the most recent version dated 29th June 2016. Everyone was working off of a different source document for the demonstration manoevres, an incredible state of affairs.

In addition, the Naval Flight Demonstration Squadron was down a member. The team consists of more than just six pilots and, for the 2016 season, they were missing an Administrative Officer, as there were not enough applicants for the role. The team decided to go ahead regardless, with the Executive Officer picking up the Administrative Officer duties.

Taking one person out of an already lean Support Officer rotation results in one less person to help cover Communications Cart and Tower requirements during practices and shows. It also creates a knowledge gap when dealing with administrative issues such as SOPs and compliance with directives. Some of the Administrative Officer’s tasks are being covered by the XO, diverting more of his attention away from primary XO tasks. Gapping the billet also sends a subtle message that some Blue Angel jobs are “more essential” than others.

It is counter to the Blue Angels’ messaging campaign concerning team concept. The Blue Angels represent the entire Department of the Navy and not just the aviation community.

I’ve seen a couple of references that claim that the report cited fatigue as a contributing factor. The report points out that the Captain was acting erratically: he didn’t sign his A-sheet, he didn’t turn on his transponder, and most importantly, he never pulled back on the throttle. However, the report states directly that he showed no signs of fatigue and had two days off before the show to rest and recuperate. There was no medical reason for his inattention that day. Whatever was wrong, the more important issue is that he didn’t report it and excuse himself from the flight that day.

According to the report, the last three Demonstration mishaps have all involved the role of Blue Angel 6, the Opposing Solo, and two occurred during the Split S manoeuvre.

In 2004, the report says that the Blue Angels were training a new Blue Angel 6 in the Split S manoeuvre. I understood that the pilot was with the U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds but my knowledge of US Military isn’t great and in any event, he was certainly in the position of Opposing Solo and performing the Split S. The pilot misinterpreted the altitude required, working from an incorrect mean-sea-level altitude of the airfield. He climbed to 1,670 feet instead of the 2,500 feet he required before initiating the pull-down. He survived, ejecting just 140 feet above the ground, 0.8 seconds prior to impact. The photograph went viral.

In 2007, Blue Angel 6 lost consciousness as a result of heavy G-force when he pulled back into a 6.8-g pull. The aircraft crashed, killing the pilot, during the final minutes of an air show at Beaufort, South Carolina.

Navy officials said yesterday (15th August 2016) that the Blue Angels stunt team will stop performing the Split S until further notice as well as setting dive recovery rules with specific airspeed limitations. The Blue Angels will also use a greater buffer to the ground for the rest of the season.

It’s a shocking case and a tragic waste. Let’s hope that some lessons, at least, have been learned.

NOTE: Copies of what appears to be the full report are hosted on DocumentCloud and Scribd. The files are the same and this is what I have used for my summary report.

Reading about this tragedy makes me wonder. Things just do not seem to add up.

Was this pilot under severe stress?

Was he using medication?

His actions seem to indicate that he was not “himself”, possibly unfit to fly.

Sad.

Definitely not on medication. The toxicology report showed no sign of drugs, alcohol or anything abnormal. No medical conditions. But yes, I agree with you, the odd lapses show that he was somehow distracted and not himself.

Odd lapses: definitely. These military demonstration pilots have one thing in common: they have been selected from the best of the best.

I was once trained for a type rating by a test pilot. He only had one single type rating in his licence: “Any Aircraft”. I have seen it with my own eyes.

What these people can do, their iron discipline, attention to detail, precision of pre-flight preparation, concentration , reaction and coordination of their every movement is awesome. This pilot was one of those or he would not have been in the team. Dropping one “ball” is out of character already. One after the other is outright bizarre. Pilot error? No, too simple to explain what happened. I believe that there must have been some other deeper cause. If not drugs and medication, what caused this? It is unlikely that it will ever be solved.

In the civilian context they would have checked out his hotel, pulled video, door times in and out, whatever to paint a more complete picture. Fight with a partner, late night, whatever.

I’d be seriously curious how many times a pilot skips the water wagon – given that it’s required and the whole concept is a team concept. How many times do they then ALSO forget to set a squawk code. This isn’t just a case of improper throttle setting – something more was going on here. Even the mistake is a double – improper height, improper throttle. This is all RIGHT after takeoff – this pilot was out of it!

Split S to ground is a regular killer for the most experienced of pilots. Working against the laws of physics. Read the books, and start thinking. The mistake is in the leadership of the team. The military grade approving this kind of flying deserves a court-mashal.

Regarding the first few lines of this report: You would certainly not fly a barrel roll, vertical up, to a Split S. The pilot made a simple roll, probably recognizing that he started it too low to go into the Split S, and continued rolling to gain altitude. A correct, straightforward decision. He finished the roll in the correct axis. This is the only difficulty in that manoeuvre. Again: The cause is on the military superior who ordered and approved this kind kind of flying.

Flight demonstrations would be much safer if only pilots would do it who paid (fully) for the airplane our of their own pocket.

« A 540° roll is not an approved manoeuvre; however, there was no particular issue caused by this deviation from the SOP. »

I wondered about this deviation. If the whole purpose of the SOP is to tightly control who does what and when, then why is it no big deal to do an unapproved 540 roll instead of the expected 180 ? And if he wanted to do a 900 roll would that have been okay also, as long as he ends up upside down at the start of the Split S ?

I feel there are still some issues that weren’t addressed by the investigation.