Crosswind Landing Gone Wrong: TUI Boeing 737 at Leeds Bradford

Leeds Bradford Airport in England, perched on a windy hilltop, is known for its challenging conditions. But even by Leeds standards, the conditions on the 20th of October 2023 were rough, as Storm Babet battered the British Isles with high winds and heavy rain.

The thirteen-year-old Boeing 737-8KS registered in the UK as G-TAWD started its day at 4am at Manchester airport with a flight to Corfu. The trip was uneventful and the flight crew had no issues. For the next leg, from Corfu to Leeds Bradford Airport, the captain, an ATPL with 14,250 hours, of which 2,800 were on type, was the Pilot Flying. The details of what happened next come from the Air Accidents Investigation Branch report.

The weather at Leeds was bad with a visibility of 4,000 metres in the rain and mist, a cloud base at 600 feet and scattered cloud at 400 feet. The flight crew were ready to divert to Manchester if need be.

As they descended towards Leeds, the crew calculated the landing performance with the wind at 060° at 19 knots. The results were outside of the aircraft limits, so they asked to enter a holding pattern at the LBA non-directional beacon. The approach controller gave them the current wind as 070° gusting 33 knots and let them know that a Boeing 737-800 had just landed.

A poster on PPRuNe asked about the landing conditions:

Is it pretty much standard for operators of this particular aircraft type in the UK to land in 35 knot crosswinds on 1800m wet runways? I think I might have been a bit hesitant to try this myself, even if legal.

The responses were characteristically blunt.

Yes, if you ever want to land at Leeds.

It’s not *always* like that. Sometimes it’s thick fog.

And sometimes its 35 knots across *and* thick fog. Like Jersey.

Leeds City? Or Leeds and Bradford International Airport? One is atop a hill and is _always _35 across, _never_ CAVOK and usually _always_ wet, sometimes. The other is an alright place for a curry.

Welcome to Leeds.

The flight crew quickly calculated the landing performance with the new information and confirmed that this wind was within limits. They began the approach, ready to go around if needed.

The controller cleared the flight to land as it descended through 2,000 feet, with a final wind check of 070° at 23 knots gusting 37 knots.

They came down crabbing, a technique used to counteract the effect of the crosswind. The aircraft is flown towards the runway with the nose into the wind, so that it continues to descend towards the centreline of the runway, rather than allowing the aircraft to drift out of alignment with the wind. The crab angle is determined by the strength of the crosswind; at the final wind check, the maximum crosswind component was calculated as 35 knots from the left.

Just before touchdown, the captain used right rudder to “de-crab” the aircraft and landed smoothly in the touchdown area. The autobrake engaged, reverse thrust was deployed and they began to decelerate. There must have been a great feeling of relief that they’d made the landing and didn’t need to divert.

When you land a Boeing 737, you control the aircraft direction using the rudder pedals, which are linked to the nosewheel steering. The nose gear has two parallel front wheels which turn in tandem. The rudder pedals will only turn the wheels up to 7° in either direction; generally plenty for maintaining control as you reduce speed on the runway. For manoeuvring at taxi speeds, for example, when turning off the runway onto a taxiway, there is a steering tiller on the captain’s side which can turn the wheels up to 78°.

In a crosswind situation like they encountered at Leeds that day, Boeing estimated that 2-3° of right rudder, increasing to 4° as they came to a halt, would be needed to keep the 737 straight and on the centreline.

As they decelerated, the captain reduced the right rudder to neutral. The aircraft started yawing to the left. He re-applied right rudder and disconnected the autobrake as they decelerated through 107 knots.

Suddenly, something juddered and there was a rattling sound. The captain could feel heavy vibrations through the rudder pedals. He released the rudder back to neutral and the aircraft drifted to the left again. He tried to reapply the right rudder carefully but every time, the pedals juddered and he released the pressure.

As they reached 86 knots, he again attempted to increase the right rudder input. He avoided the wheel brakes and cancelled the reverse thrust. This is advised for handling deviations from the runway centreline, which would increase their landing roll but could keep them from skidding. With the crosswind, the wet runway and no autobrake or reverse thrust, they needed a lot more runway than usual but they still had enough distance to come to a halt, if only they could stay on it.

The captain reduced the pressure on the right rudder in response to the juddering but the aircraft kept yawing to the left. He carefully applied about 1.8° right rudder. It was obviously not enough. They were going to come off the runway.

As they approached the runway edge, the captain remembers reaching for the tiller, trying to keep them on the runway. It didn’t work. The aircraft careened off of the edge of the runway at 55 knots (63 mph, 101 km/h). It continued fully off the runway for about six seconds and then came to a halt in the muddy ground.

The crew followed normal shutdown procedures and evacuated the aircraft with no injuries.

Another poster on PPRuNe wrote that a team of British Airways crash recovery engineers travelled up from London by road to deal with the difficulties of towing the aircraft back onto solid ground. The report doesn’t mention this but it is clear that the aircraft was well and truly stuck.

A significant amount of mud had accumulated within all landing gear bays, underneath the wings including flap surfaces, and over the fuselage towards the tail. There was mud within the engine bypass and engine cowlings.

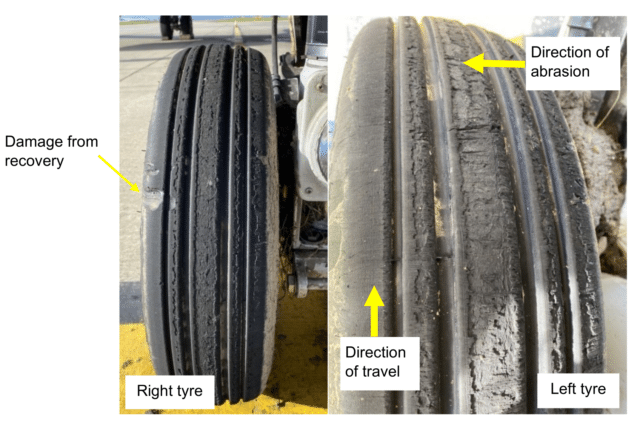

Surprisingly, the main gear and the nose gear were undamaged and the aircraft structure was intact. The tyres were a mess, probably from the recovery process, but none of them showed any symptoms of a locked wheel condition or rubber reversion, which is when tyres skidding over water causes the rubber to revert to its original state and lose its grip on the runway.

In fact, the Boeing 737 is shown as flying again just ten days later.

An examination of the runway gave the investigators more information.

The tyre tracks started at taxiway LIMA, showing six tracks along the runway, two either side from the main landing gear wheels and two parallel tracks from the two nosewheels shown coming from the right bottom corner in the photograph above. These marks were left as the surface temperature under the tyres became hot enough to turn the water on the runway into steam.

But about 840 metres (2,750 feet) along, that nosewheel track changes from two clear tyre marks to a single tyre mark.

That single track continues for over 200 metres until the point where the Boeing left the runway.

The two tyres were still connected to the nose-wheels when they towed the aircraft back. The single track can only be explained if the two tyres were turned to one side, perpendicular to the direction of travel.

The physical evidence backed this up: the nosewheel tyres were badly abraded all around their circumference, the effect of being turned to the side, rather than rolling in the direction of the travelling aircraft.

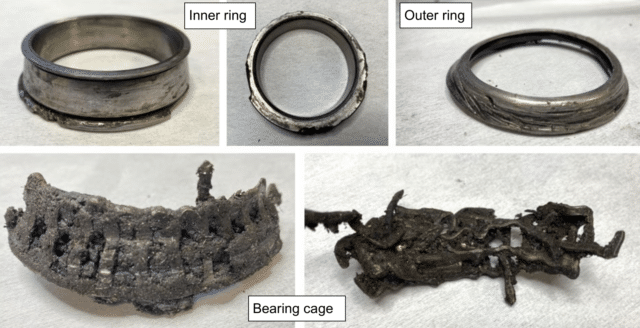

Once they took the tyres apart, they found that the inner axle bearing had failed in the left nosewheel. Each nosewheel has an inner bearing and an outer bearing that hold the wheel onto its axle. These are replaced as they wear down; this particular bearing had been fitted during a routine wheel overhaul in September 2022.

The left nosewheel had a lot of play on the axle but this likely happened as they pulled the aircraft out of the mud. The outer bearing was undamaged and the damage to the wheels and the axle did not show any signs of excessive movement during the landing.

The failed bearing would have caused the rattling sound and the juddering that the pilots could feel through the rudder pedals. However, this did not directly impact the steering during the landing roll. The nosewheel steering worked as expected, using the rudder pedals. Or at least, that was true until the nosegear wheels turned sideways.

The only way to turn the wheels so suddenly would be to use the steering tiller. The captain remembered using the tiller at the last minute, but based on the tyre tracks, he must have reached for the tiller earlier, at a much higher speed than the tiller is made for. Turning the wheels at that speed forced them into an extreme angle. They dragged sideways across the runway surface, causing that single track. For those last 200 metres, they had no way to steer the aircraft as it veered off of the runway.

The final report concludes that the initial phase of the landing roll was normal until the captain disconnected the autobrake and stowed the reverse thrust early, slowing their slow, as it were. This reduced rate of deceleration did not help against the crosswind from the left which was causing the aircraft to drift. Plenty of right rudder was needed to correct it.

The deviation from the centreline, resulting from the strong crosswind from the left, required more right rudder input than was applied, in order to correct it. Additional use of differential braking to assist was also available. There was an unusual juddering from the nosewheel reported by the crew likely resulting from the failure of a nosewheel bearing. There was no mechanical defect identified by the investigation which would have prevented the crew from applying the additional right rudder that was available to keep the aircraft on the runway.

However, the crew’s actions may have been influenced by the nosewheel juddering.

If the captain had kept continued pressure on that right rudder pedal, applying normal control inputs after a hairy landing, he would have kept the Boeing 737 on the runway. But that juddering caused him to pause. He instinctively reduced the right rudder every time he felt that judder. As a result, he didn’t have enough turning power to keep the aircraft on the centre-line. Reaching for the steering tiller while still well above taxi speeds just made things worse. A relatively minor mechanical issue in challenging weather conditions cascaded into a serious incident.

Despite the dramatic end to their flight, all 195 passengers walked away unharmed and the Boeing 737 suffered remarkably little damage.

You can download the full report from the AAIB .

So can you show me in the landing performance calculations where you add “and a Boeing 737-800 just landed” in the formula? Obviously this term makes a big difference.

Is that under the “So what’s your problem?” section?

I sense just a wee tiny bit of peer pressure.

I see it was opened in 1931. Surely they could determine the usual wind direction and align a runway with it back then?

Until 2005 (2003?), there was a second shorter runway aligned 9 and 27, however it was closed in October 2005 and converted into a taxiway. That seems to have been the original runway, well aligned for the prevailing westerly winds.

Giving the runway heading in the first few paragraphs would make this easier to read. I found it all a bit of a puzzle up until I saw the aerial picture of the reciprocal end.

Even so, I clearly don’t understand cross-wind limits for this type of aircraft. IIRC for simple single-engine piston it’s just wind strength × sin(θ) but that doesn’t make sense if 80° off at 19 knots is out of limits but 33, or even 23, at 70° off is in. Anybody illuminate?

The AAIB was baffled as well:

Maybe they entered a wrong number?

Or perhaps the additional headwind component helped shorten the braking distance? “Landing distance required” (including safety margins) was 95% of “landing distance available” under the conditions they landed at.

Ah, read the report now. It was the landing distance which was the concern, not the cross-wind limit.

I didn’t even notice that I hadn’t given the runway heading; that was careless of me. Thanks to Mendel for highlighting the AAIB response.

Unfortunate. The crew made a good landing but a small defect confused the captain.

The crabbing technique is the only one for a crosswind landing in an air liner with under wing engines.

Tail mounted engines make it possible to land with cross control and under full control right up to the last moment.

The same thing goes for high wing aircraft, but they are usually propeller driven.

The captain in this case was unlucky.

Nobody was hurt, that is the most important thing.