Cessna 172M forced landing after go-around in New South Wales

On the 15th of October 2023, a private pilot rented a Cessna 172M from Air Gold Coast for a private flight from Gold Coast Airport, Queensland, to Murwilumbah, New South Wales.

The aircraft, registered as VH-JUA, was 47 years old and had been in Australia since 1989. It had over 14,000 hours, although there were only 2,600 hours on the engine since the last overhaul. The pilot was quite a bit younger than the plane and had held a recreational licence for ten months, with a total of 107 flight hours, 72 of which were on the accident aircraft. The pilot continued to take dual and solo flights with the operator; however, on the day of the accident, it had been 121 days since the pilot’s last flight.

Murwillumbah Airfield has a 19/01 grass strip which the report gives as 1,045 metres (3,428 feet), however, it is commonly listed as 800 metres as it has a displaced threshold of 245 metres on runway 19, because of industrial buildings and trees at the northern end.

The aircraft was filled to full fuel and the pilot’s departure and flight to Murwillumbah was uneventful until the final approach to Murwillumbah. That day, the weather was clear with light wind. With a temperature of 26-27°C and dew point at 16.7, there was a high likelihood of carburettor icing. The pilot joined the circuit at Murwillumbah, joining downwind for runway 01, so with the full length of the runway available.

The pilot felt that the approach was stable but that the aircraft was too high on the approach, about 300-350 feet above the ground as the Cessna crossed the threshold, and decided to conduct a go-around. The pilot configured the aircraft for the go-around and applied full throttle. The engine made a loud bang. It didn’t seem to be responding with enough power for the go-around. The fuel mixture was rich, the master switch was ON, the magnetos were set to BOTH and the carburettor heat was OFF. With so much going on, the pilot does not recall checking the engine RPM but it seemed clear that the Cessna did not have enough power to climb.

There was another person on the airfield, who was standing outside of a hangar at about halfway along the runway as the Cessna approached. The engine sounded as though it was running at a low power setting. The Cessna came in for landing and crossed the threshold at approximately 100 feet above the ground. As it passed the mid-point of the runway, the nose dipped down and then a moment later, the aircraft pitched up. There was a bang or ‘pop’ sound, which the witness thought sounded like the throttle was pushed forward too quickly.

Although the pilot recalls applying full power at the threshold, it was quickly obvious that there was not enough runway left to attempt to land. The aircraft did not have enough height to manoeuvre, let alone turn around and try to land on runway 19. Fast approaching the buildings at the end of the runway, the pilot raised the nose. The speed dropped and the Cessna began to buffet in warning of an impending stall. The pilot lowered the nose and saw a cane field ahead. There was no choice but to land.

The cane field was just one kilometre (half a mile) north of the airport. The pilot fought to maintain control of the aircraft and held the nose up in a long flare before landing hard. The right wing was crushed and it was clear that the aircraft was badly damaged.

The pilot had only a minor injury from the shoulder strap and promptly shut down the aircraft and climbed out.

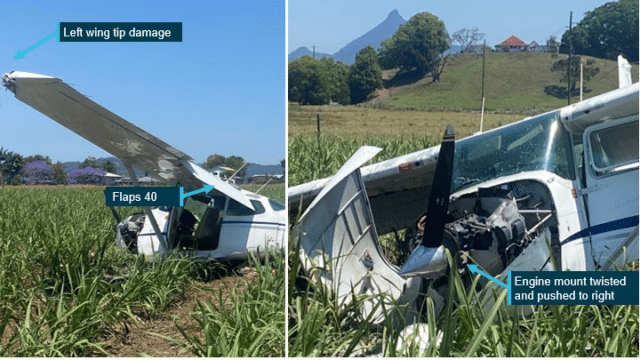

The photographs of the wreckage show substantial damage to the Cessna. The nose gear and right landing gear broke off as the aircraft touched down in the field. The left wing tip, fuselage and right wing were damaged as the gears collapsed and the engine was crushed to the right.

Notably, the police photographs show a nose-wheel steering towbar which was lying loose on the front passenger seat rather than stowed under the seat or in a net in the baggage compartment. The pilot was lucky that the towbar didn’t do any damage.

OzRunways, an Australian site, includes a flight tracking service focused on Australia and New Zealand. This records the location, altitude and speed at five-second intervals. The altitude information is given in 100 feet increments, so it is not exact. However, based on their recorded data and the terrain of the runway, the investigators concluded that as the Cessna crossed the threshold, it was at 80 feet above the runway travelling at 58 knots ground speed; a perfectly reasonable approach. The Cessna then continued at the same height until the mid-point of the runway, at which point it climbed to 200-280 feet at 60 knots before descending towards the field.

This mirrors the recollection of the witness, which was that the Cessna came in normally but continued at ~100 feet above the runway before rapidly increasing the engine power to climb away.

The Cessna seemed to have been perfectly positioned for landing as it crossed the threshold. There’s no explanation for why the pilot believed that the aircraft was 300 to 350 feet above the runway. The pilot also believed that the go-around started at the threshold, whereas in fact the manoevre commenced at the mid-point of the runway, which shows that the pilot was struggling to keep up with events, effectively running behind the plane.

There was no sign of anything wrong with the engine and significant fuel was spilled at the crash site, so lack of fuel was not an issue. Both the witness and the flight data show that the aircraft held its speed and height across the runway and then climbed a few hundred feet. The engine may have faltered when the pilot applied full power too abruptly, but it quickly recovered.

The key point is that having decided to go around, the pilot did not follow the checklist.

The Pilot’s Operating Handbook for the Cessna 172M has the following procedure:

- Throttle – full open

- Carburettor heat – cold

- Wing flaps – 20°

- Airspeed – 55 kt

- Wing flaps – retract slowly

For non-pilots: During landing, the flaps on a Cessna 172M are typically set to full (40°) to help slow the plane and provide better control. You generally want full flaps for landing and no flaps for taking off. This means that if you decide to abort a landing, you need to retract the flaps to reduce drag so you can quickly climb away. The checklist has this in two stages, reducing the flaps to 20° as you increase speed and then retracting them completely.

And yet, the photograph at the crash site, taken by the pilot, tells a different story.

When describing the decision point to land in the field, the pilot told investigators that the risk of stalling was a worry, so it seemed safer to keep the flaps at 40° to maintain as much lift as possible and reduce the stall speed. Thus, the pilot was aware that the flaps were still at 40° but did not associate full flaps with the lack of power and slow climb.

The ATSB concluded in the final report that, as the Cessna managed to climb ~200 feet with the flaps set to full, there was not any issue with the engines providing power.

Findings

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the collision with terrain involving Cessna 172M, VH-JUA, 1km north-east of Murwillumbah, New South Wales on 15 October 2023:

Contributing factors

- During the go-around, it is likely the aircraft was incorrectly configured resulting in reduced climb performance.

Other factors that increased risk

- unrestrained object in the aircraft increased the risk of serious injury to the pilot

Air Gold Coast, the operator of the Cessna, has since updated the quick reference handbooks with clearer procedures for going around. They also now require pilots to have more recent flight experience before hiring their aircraft for private flights.

The Cessna appears to have been scrapped, as it is no longer listed under their training aircraft and there are no further flights or transactions.

My recollection of getting checked out on a C172 (after getting a private license on a C150 and moving to the larger aircraft for an instrument rating) is that only the first ~half of flap lowering contributed seriously to lift. (I’m sure the recommendation for a short-field takeoff was nowhere near full flaps, but I’m not as certain that was the recommendation for soft-field takeoffs, where I was taught to get off the ground as quickly as possible then reduce flaps gradually, while still in ground effect, as airspeed picked up.) It’s possible this pilot was trained differently, or that the aircraft itself differed. (I couldn’t tell you exactly which version I was flying, but it was far from new in 1973.) It’s also possible he wasn’t remembering the best flap setting for a panic climb; that would be in line with having not flown in 4 months, Sylvia’s observation that he was “behind the aircraft”, and the witness report that the plane was low and level over half the runway (a weird move for a short field — either put it down or get out and try again).

All of this is recollection from a long time ago; anyone with fresher knowledge of older C172 should correct me.

Isn’t this why you train touch-and-go in flight school? To quickly reconfigure the plane to accelerate and climb?

IIRC, my instructor had me do touch-and-go so we could practice more approaches/touchdowns into a given time than if we’d slowed enough to taxi back to the start of the runway. (This did require a long-enough runway with little-enough traffic, but there was at least one field near Boston that supported this.) We didn’t actually practice breaking off an approach close to touchdown, which could also have been useful but probably wasn’t in the syllabus.

I agree with Chip and Mendel. Of course their comments dovetail with Sylvia’s summary.

Carb ice is not very common in temperatures of 27C, but not entirely impossible either. But it seems that this was not the case here.

Of course, iof there had been any ice in the carburettor it would have melted very quickly before any investigator would have been even close to the wreckage.

I cannot remember how many hours I have flown on the C172, possibly hundreds. I do not recall any major differences between the models.

The original version did not have the rear windows, but a straight fuselage. The earlier versions with the windows at the back of the cabin still had a handle for the flaps. I preferred that over the electric version.

But the major point is that the pilot indeed seemed to have been “behind the aircraft”. He did not realise his height. Was it 350 or 200 ft? Normally not very important, but if the pilot misjudges his height and still is well above the ground over the mid=point of an 800 metre long runway, it is getting critical.

The 172 can be landed and stopped in about 400 metres, but that does not leave much of a margin.

I have landed a Cessna Citation on a runway of 700 metres (Castlebar in Ireland, long closed). I found information that the runway was 2000 ft long and 70 ft wide.

The eyes of some of the pilots of a flying club nearly fell out, but it was possible. Albeit only on a dry surface.

The cardinal point here is that “flaps 40” definitely causes too much drag on a 172 for a go-around. A setting of 20, with a gradual reduction as the aircraft climbs away and gains speed

The main point is that nobody got hurt, only the pilot’s pride.

And it is sad to see another C172 being scrapped. They were great little airplanes. Still are.

Re “behind the aircraft”:

Captain of a Learjet to his copilot: “You want to shape up, you are ten miles behind the airplane”:

Copilot: “That is fine with me captain. I can watch you crash it from ten miles behind”.