Captain Fired After Nose-Wheel Landing

The Captain of a Boeing 737-700 landed hard at LaGuardia Airport, collapsing the nose gear. But it’s actually what happened leading up to the hard landing that makes this particular case interesting. The final report has not been released; however various public documents, including the Chariman’s factual reports, are now available on the NTSB site:

Southwest Airlines flight 345 on 22 July 2013 was a scheduled passenger service from Nashville International Airport in Tennessee to LaGuardia Airport in New York carrying 145 passengers and 5 crew. The Captain started her sequence of trips on the 21st of July and the First Officer began his on the 19th. They met up on the morning of the 22nd at Los Angeles International. They had not previously flown together. They flew into Nashville International Airport, arriving at noon, and changed aircraft to the Boeing 737-700. The Captain invited the First Officer to do the next leg as the Pilot Flying and the Captain would take the role of Pilot Monitoring. An American Airlines pilot was in the jumpseat of the cockpit for the trip to New York.

The American Airlines pilot in the jump seat described it as a normal flight.

Once the flight was airborne, both accident crewmembers were very personable. They talked shop and he did not see any issues personality-wise. The captain occasionally gave the accident F/O guidance and he would say ok. The jumpseat occupant did not see any issues in that regard. He thought the accident F/O might be new, based on how the captain was guiding him. The accident F/O made small procedural errors like one time forgetting to push the LNAV right away. During the descent, the captain was giving the accident F/O small instruction tips.

The initial flight was uneventful until they drew close to LaGuardia Airport. There was significant weather in the area and some thunderstorm activity. While they were holding because of the weather, the First Officer briefed a visual approach to Runway 4 backed up with the ILS to Runway 4. They computed the landing distances for the wet runway and the Onboard Performance Computer bracketed out Autobrakes 2, which means that the 2 setting for autobrakes would be not enough for the circumstances. They chose setting 3 for the Autobrakes. During the briefing, the Captain asked if the First Officer wanted Flaps 40. The First Officer agreed, “Yeah, since it’s wet and stuff. Yup.”

The Captain also mentioned that tailwinds on arrival were reaching as high as 30 knots. It’s clear at this point that she was concerned about their landing distance at LaGuardia.

The first officer said that about 98% of the time, he had landed with a 30º flap setting, but he estimated that he had landed with 40º flaps about 30-50 times during the previous year-and-a-half. He stated that a pilot had to be “on his game” with a 40º flap landing, since the airplane had more drag, it required a higher power setting, and a pilot needed to keep a better check of airspeed, because it was quick to decrease. He characterized a 40º flap landing as a power on landing without the pilot reducing power until the airplane was established in the flare with the main gear about 3-4 feet above the runway.

Of note is his description of a 40º flap landing as a power on landing: that is, one flies the aircraft to the ground as opposed to gliding it. The power is only reduced at the very last moment.

The American Airlines pilot in the jump seat barely recalled the conversation.

He remembered a discussion earlier in the flight between the crewmembers that the captain had only been to LGA once before and the F/O had been there a few times. There was a little discussion about going into LGA, but he did not recall much. He thought there was a concern about the length of the runway and the water. He did not remember a discussion about not being fast or high on the approach. He was not paying that close attention.

They were still almost an hour away from landing. There were thunderstorms and clouds between them at the airport; however LaGuardia airport itself appeared to be clear and the aircraft landing before them reported no turbulence on approach.

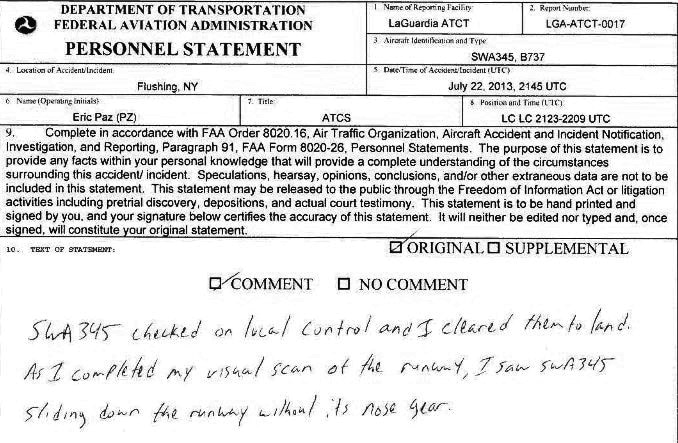

They broke out of the cloud at about 2,000 feet as they were passed to Tower. The flight crew completed the before landing checklist. The Tower Controller at LaGuardia cleared the aircraft to land.

Up until then, both crew members characterised their cockpit interactions and CRM as good. But as they descended towards the airport, it started to break down.

Interviews with SWA management and training personnel, indicate that the correct protocol would be that when the autopilot was engaged, the PF would be responsible for manipulating the FMC or commanding the PM to do so. The PF would also command a flap setting, which the PM would accomplish. It would not be normal procedure for the PM to manipulate the FMC, flaps, or gear without being asked or commanded.

The First Officer’s recollection was that during the original briefing, the Captain made the decision to use Flaps 40 as she was concerned about the landing distance with the runway being wet. He agreed.

He described her as wanting to be in control. On the approach, he noticed that as he was slowing from 250 knots to approach speed, she started spinning the Mode Control Panel dials without him asking her to set his speeds. As he was about to call for a speed, he found she was ahead of him and already dialling it in.

Under normal circumstances, the Pilot Flying would either set the speeds himself or request that the Pilot Monitoring did it. The First Officer said that it happened that a Captain would say “Hey, I’m going to do this for you” and he would say OK. However, he did not recall the Captain asking or saying anything until after she’d made the changes.

The Captain remembers looking out the window and thinking that the pitch angle did not look good. She realised that they did not have flaps 40 set as per the briefing, which means their performance calculations were wrong. The First Officer, as Pilot Flying, had forgotten and only called for the flaps to be taken as far as 30º.

As Pilot Monitoring, it is her responsibility to notify the pilot flying of anything she notices. However, she should not make changes to the configuration of the aircraft: it is the Pilot Flying’s job to request or make changes.

When they hit the final approach fix, the aircraft was configured for landing with the gear down, flaps 30 and speed brakes armed. The next important phase of the approach was the aircraft reaching 1,000 feet above ground level. The aircraft was on autopilot with the First Officer keeping his hands lightly on the controls ready to take over.

The 1,000 foot call-out is important because the aircraft must be fully configured for landing at this point. If the aircraft is not yet completely configured, the correct response is to break off the approach and go around.

In her interview, the Captain said that she informed the First Officer that the flaps were set to 30 and she was going to set them to 40 and that the First Officer confirmed this. The First Officer’s recollection was that she simply changed the setting and told him afterwards. He was not sure if this happened before or after the 1,000 foot call out although he did know that no further configuration changes should happen after that time.

The cockpit voice recorder has the exchange.

| 17:43:03 | First Officer | A thousand feet. Thirty six and sinking six hundred. |

| 17:43:06 | Captain | Thousand feet. |

| 17:43:11 | Cockpit Area Microphone | [sound similar to trim] |

| 17:43:30 | Captain | Oh, we’re forty |

| 17:43:31 | First Officer | Oh there you go |

| 17:43:32 | Cockpit Area Microphone | [sound similar to flap handle movement] |

| 17:43:34 | Captain | That was like an hour and a half ago that we briefed that. I’m sorry |

| 17:43:36 | First Officer | [sounds of laughter] |

| 17:43:37 | Captain | All the sudden I started looking at that runway going ‘something’s wrong.’ |

| 17:43:39 | First Officer | Okay. |

| 17:43:40 | Captain | Okay flaps are at forty. |

| 17:43:41 | First Officer | Forty, we got it. Green light. |

| 17:43:42 | Captain | Green light. |

The captain said that when she realized that the flaps were not set to 40º, she was pretty certain that they were on the glideslope. She did not recall at what altitude the flaps were set to 40º but it was a “good time” prior to the 500 foot call out. She said she did not remember if they were below 1,000 feet when the flaps were set to 40º, but the flaps should have been down by then. Later in the interview, she stated that “the call for flaps 40 was made with plenty of time before the 500 foot callout. By the book, it would have been a go around.”

The Captain watched the landing through the HUD, which means she was watching the aircraft on the glideslope of the ILS. The Pilot Flying was flying a visual approach and his reference for this was the PAPI.

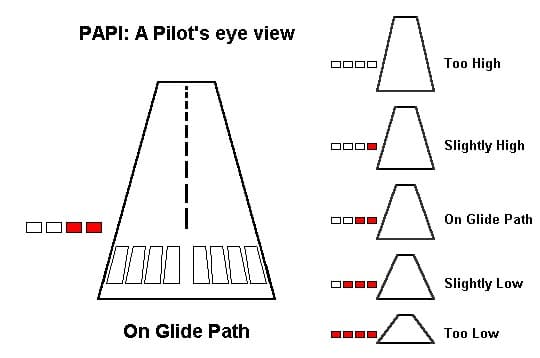

The Precision Approach Path Indicator (PAPI) is a visual display which provides vertical guidance for the approach path. In a normal approach, the PAPI would show two whites and two reds. More whites means that the angle of the approach is too high. More reds than white means that the angle of the approach is too low.

At around 500 feet, the First Officer disconnected the autopilot and autothrottles. The PAPI indicated two whites and two reds and he was satisfied with his airspeed and crosswind corrections. As far as he was concerned, everything was fine.

The Captain was watching through the Heads Up Display which gave her additional information, including wind.

The first officer said that out of the corner of his eye he noticed that the captain appeared to be somewhat uncomfortable with the approach. As they crossed over the runway overrun, he noticed that the PAPI indicated 3 white lights and one red, which meant that they were a little high on the glidepath. He knew that he would need to make a slight correction to land in the touchdown zone. He said that he then felt the captain’s handon top of his on the throttles, and she pulled his hand and the throttles back retarding the throttles to what felt like the idle position.

He said that he did not recall her making any comments, before, or during her retarding the throttles. The first officer said that he had never had a captain put his/her hand over his on the throttles during an approach, although some captains would guard the throttles by placing their hand below his behind the throttle levers. He said he never had a captain pull the throttles back on him while he was flying an approach.

As the First Officer continued his final approach, the PAPI shifted from two reds and two whites to three whites and a red, thus signalling that the aircraft was slightly high. The Captain, watching from the Heads Up Display, said that she believed that the aircraft was going too fast and that the pitch was too low.

She said it felt as though they were being pushed over the ground. She said that over the threshold, she verbalized that they had to get the airplane down, and she put her hand over the first officer’s hand on the throttle, but was not touching his hand. She said there was no standard procedure for that, but was certain that it was explained as a technique. She said she had verbalized that they had to get the airplane down on the ground, but she did not get the reaction she needed from the first officer, and did not believe she had time to try to articulate it again. She said she believed that if she did not act, the airplane would have continued to float past the touchdown zone.

Another relevant point is that the Captain had been watching the approach on the Heads Up Display. The Jeppesen approach plate (11-1) for ILS Runway 4, states that the VGSI [PAPI] and ILS glidepath are not coincident. This means that even coming down perfectly on the PAPI, the aircraft could show as high on the ILS glideslope. The NTSB have so far makes no comment as to whether this may have led the Captain to overreact as the approach appeared higher than it was.

Regardless, it is quite clear from the data that at the runway threshold, both the glideslope deviation and the PAPI visual guidance indicated that the aircraft was high.

From the transcript of the Cockpit Voice Recorder

| 17:44:00 | Captain | Clear to land. |

| 17:44:07 | Captain | Correcting nicely. Don’t get too much on the speed. |

| 17:44:12 | Captain | Ooh. |

| 17:44:12 | First Officer | Come on. |

| 17:44:14 | Captain | One hundred. Gotta get [unintelligible] |

| 17:44:17 | Captain | Get down. Get down. Get down. Get down. |

| 17:44:23 | Captain | I got it. |

| 17:44:23 | First Officer | Okay you got it. |

| 17:44:26 | Captain | [sound similar to inhalation] |

| 17:44:26 | Captain | [expletive] |

| 17:44:26 | Cockpit Area Microphone | [sound of impact] |

The two things that jump out at me here are that her phrasing is not clear and non-standard (most significantly, “I got it” rather than “I have control” when she is taking control of the aircraft. The second is that if the approach was not stabilised: she should have called for the first officer to go around, rather than try to correct the issue and take control at low level.

The American Airlines pilot in the jump seat was unable to say much about the final moments.

The airplane was low; he was thinking they were low and the nose still looked low. He was not

familiar with the airplane and was seated in the jumpseat, but it did not look right. He thought the altitude was in the 150-200 foot range. There was a 2-4 second delay after the throttles went to idle and then the captain said my aircraft and the accident F/O lifted his hands up in the air. He did not notice what the F/O did when the captain pulled the throttles to idle.The jumpseat occupant was concerned about the pitch being low so he was looking outside the airplane. After the transfer of control, he seemed to recall a pitch down at that point. The airplane pitched over further down. He became tunnel visioned on the cement and he did not look back inside. The ground was coming up quicker than he thought it should have.

The First Officer said that he acknowledged and released control of the aircraft and then scanned the altimeter and airspeed. He looked out at the rapidly approaching runway and said that all he could think to do was brace for impact. There was no time to say anything.

The Captain may have let the nose wheel drop drying to catch the ILS glideslope and by the time she realised, it was too late for a correction.

The captain said that she saw the nose hit the runway, and felt the impact of the nose hitting, but did not feel the nose wheel hit, and had no recollection of which gear hit first. She said it was a hard impact, and the airplane started sliding. She said she tried to control the airplane with rudder and brakes. The airplane veered slightly to the right before stopping on the runway.

Asked his impression of what section of the airplane touched down first, [the American Airlines pilot in the jumpseat] said the nose wheel first. He did not remember how far down the runway they touched down. He did not recall any markings on the runway before they touched down. He was looking “at concrete” but he was looked at the centerline. When they did the pitch over when the nose hit, it felt like “one big jarring moment” and then the nose was on the ground. He did not feel an arresting sensation like the nose wheel touched first and then collapsed. The nose was on the ground and they were sliding and he thought a panel or 2 became dislodged in the cockpit. After a few seconds, smoke entered the cockpit from underneath the floor boards and around the pedestal.

Boeing have submitted their report based on the Flight Data Recorder:

The FDR data show the airplane configured for a flaps 40 approach with the autopilot and autothrottle engaged, and on glideslope and localizer at 500 feet Radio Altitude (RA). The autopilot and autothrottle were disengaged at approximately 410 feet RA. As the approach continued, the airplane began deviating above the glide path due to increased thrust and a slight increase in pitch attitude while maintaining the selected speed of VREF40+6. At the runway threshold, the airplane was at 60 feet RA and on a 2.1-degree glide path. The throttles were reduced to forward idle at 46 feet RA, and at 32 feet RA the cockpit voice recorder indicated that a transfer of control was made from the First Officer to the Captain. After the transfer, but prior to touchdown, the control column relaxed to neutral deflection, the throttles were advanced.

Due to the early reduction in thrust to forward idle, the absence of control column input prior to touchdown, and the nose-down pitch tendency in ground effects, the airplane pitch attitude decreased to a nose-down attitude of -3.1 degrees and touched down on the nose gear prior to the main gear touching down.

In other words, the Captain pulled the power back because she believed that they were too high. The nose pitched down and as the aircraft touched down on the runway, it landed nose-gear first.

The investigation is still in progress; however the Captain has been already terminated by the airline.

Fortunately it was a “good landing” in the sense of the old joke “a good landing is any landing you can walk away from”.

My heart goes out to the captain. It is always sad to see anyone’s career ruined because of a mistake.

But in aviation mistakes often cost lives.

There is mention, as I mentioned before, of a tailwind in the order of 30 kts.

NO commercial airliner is certified to land with a tailwind component in excess of 10 kts.

Sadly, unless the strength of the tailwind component was misstated, I am convinced that this was the blunder that nailed the captain and ended her career.

The text here is highly suggestive that the crew were informed about it before initiating the approach. They should not have made their approach to that runway. If and no other runway was available the thunderstorms were a matter of concern, they should have diverted. From the above my guess is that the crew allowed pressure to prevail over good judgement. Sad !

From the Operations document:

The KLGA Automated Terminal Information Service (ATIS) reported that it was clear at the airport and the surface winds were easterly at 10 or 11 knots. However the captain stated that the tailwinds on arrival reached as high as about 30 knots.

[…]

The accident occurred about 1740 EDT or 2140 UTC (Z). The closest reported weather observation to the time of the accident was approximately eleven minutes after the accident at 1751 EDT or 2151 UTC.

That observation was as follows:

METAR KLGA 222151Z 04008KT 7SM FEW030 SCT050 BKN075 0VC130 25/22 A2985

*Decoded: Terminal report for LaGuardia Airport, July 22 at 2151Z, wind from 040 at 8 knots, visibility 7 statute miles, few clouds at 3,000 feet above the ground, scattered clouds at 5,000 feet, broken cloud layer at 7,500 feet, overcast layer at 13,000 feet, temperature 25ºC, dew point 22ºC, altimeter setting 29.85.

Also interesting is this from the Boeing Performance Analysis:

A 10-knot right crosswind was present at the start of final approach but diminished as the airplane descended, and the wind changed from a tail wind to a headwind, with the headwind reaching approximately 5 knots at touchdown (Figure 2)

However, if the Captain thought there were tailwinds as high as 30 knots then as you say, it makes no sense that she still wished to continue.

Let me be very specific: I am making general statements that can apply (and have applied) to other aviation accidents. I use Sylvia’s article as a template, in the full knowledge that the incident described is still under investigation and the full facts are not yet known.

But: There is another disturbing titbit in the article. Reference is made to “starting the sequence of trips” on previous day or days.

It also mentioned a “change to the Boeing 737-700”. Which rises to the question: did they change to a different version of the 737 during a (long) duty period ?

Many accidents occur at the end of a long duty period, sometimes involving sub-standard rest facilities and the maximum number of sectors the crew may fly during that duty period.

Most airlines are very, very sticky when it comes to SOP’s and crew coordination.

During a manual approach (therefore by definition Cat 1) the PF will also manipulate the power settings.

If he or she is not very experienced, more so BECAUSE of inexperience, the captain must at all times ensure that the co-pilot is fully kept “in the loop” and at all times aware if the captain makes an adjustment to power setting or any other change that may affect the operation.

Surprisingly, the captain seemed to have violated that rule.

If the wind or any other factor is out of limits a go-around is mandatory.

The METAR did not show an unusual tailwind. It would therefore seem that on-board systems (GPS, FMS) were showing a 30 kt tailwind at some time during the approach, according to the captain.

Even if this was momentary, she should have been alert and ready to go around. She did not.

A 40 flap landing is nothing that puts any undue demands on the crew. Proper speed control (and therefore per definition proper power setting) and – as a result – proper pitch should have ensured a good landing. Holding the correct pitch and taking the power off at about 30 ft RADALT above the runway should ensure that the aircraft will settle – on it’s main landing gear! – with a slightly firm (positive) contact.

For some reason, during the final stage the aircraft seemed to have been in an unusually pitch-down attitude.

The captain seemed to have made some capital errors:

SOP’s were not properly observed,

Crew coordination was poor,

Pitch and speed control were poor,

The 40 landing was not properly briefed,

The captain failed to call for a go-around when she became suspicious of a potential strong tailwind.

When reading Sylvia’s account, all this is suspiciously similar to other incidents, caused by crew fatigue. Long travel distances dead-heading between home and airport from where duty is starting, many sectors, arriving some hours before commencing the first sector with inadequate sleep on the couch in a crew lounge etc.

In this comment, I reiterate, I am very much speculating. It is not my intention to jump to any conclusions, only to try and come up with some possible causes based on the above article.

But it would not come as a surprise if crew fatigue would be identified as a factor.

Airlines do have a habit of blaming an accident by labelling it’s cause as “pilot error” !

Extremely poor CRM. Going around would have been the only prudent thing to do to fix this horribly destabilized approach.

On a related note, about an hour before this happened, I was holding short of 04 at about the point where they came to rest. It was a windy, stormy day, but we got out with no real problems.