Any Landing You Can Float Away From: Successful Ditching in the Arctic

On the 29th of July 2024, a light aircraft encountered engine trouble off the coast of Greenland and was forced to ditch in the North Atlantic.

The aircraft was a Piper Malibu (PA-46-310P), registered in Germany as D-EOSE, one of the earliest pressurised aircraft available to the general aviation market.

Two pilots were on board, the joint owners of the aircraft. Although both were qualified, all flights on the Malibu are operated as single-pilot: for each leg, one flew as pilot in command while the other travelled as a passenger. The pilot in command on the day of the incident held his ATPL and had 17,802 flying hours, with 107 hours on type. The passenger that day held a PPL with 963 total hours and 131 hours in the Malibu.

The Malibu had been inspected that June in preparation for a long-distance flight to the US. The owners planned to fly from their home base in Germany to Oshkosh, Wisconsin to attend EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, and then back again.

They carried survival equipment on board for the water crossings: an inflatable life raft with emergency locator beacon, two personal locator beacons, a satellite telephone, emergency flares and an LED SOS flare.

They attended the airshow and were now on their way back home.

Before each flight, the owners topped up the oil level to eight quarts. On the 28th of July, the day before the incident, the pilot in command recalled adding approximately 0.2 US quarts of oil during the preflight inspection.

They flew from Rimouski (CYXK) to Goose Bay (CYYR) without incident.

CFB Goose Bay is a Canadian Forces base located in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador, operated by the Royal Canadian Air Force. It’s a key stop on the North Atlantic Ferry Route, which makes it possible for short-range, single-engine aircraft to cross the North Atlantic with refueling stops in Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland, and Iceland.

They stayed overnight at Goose Bay. Their next leg was from Goose Bay to Narsarsuaq Airport (BGBW) in Greenland, a distance of 676 nautical miles.

Narsarsuaq Airport is the principal airport in South Greenland. The small settlement of Narsarsuaq, population 123, is centered around the airport. A new airport nearer to Qaqortoq, the largest town in South Greenland, is scheduled to open in a few months, in April 2026; Narsarsuaq will be downscaled to a heliport. There’s uncertainty as to the future of the settlement once the runway closes; the local hotel and the aviation museum have already announced that they will shut and some 70 people have already been laid off.

(You may be wondering about when I saw this, if I did a frantic investigation into whether I could get there before the aviation museum closes: you’d be right!)

However, in 2024, Narsarsuaq was still an important refuelling point for small aircraft crossing the Atlantic. On the morning of the 29th of July, the pilot flying the next leg from Goose Bay to Narsarsuaq did the pre-flight inspection.

The pilot found no issues with the aircraft. The oil level indication was full, meaning that the oil level was at 8 quarts, so there was no need to top up. The life raft was in the cabin and accessible. This water crossing was the most dangerous leg of their trip. They both put survival suits on up to the waist, leaving them unzipped for comfort.

They departed normally and climbed to Flight Level 210 (~21,000 feet) for the cruise. All indications were in the green. They recalled that the weather was “nice”.

Air Traffic Control asked them to descend to FL180 (~18,000 feet). The pilot reduced the power to 65% and leaned the fuel flow in preparation for the descent. The pressurised cabin allowed them to cruise comfortably at FL180 despite the fact that outside the temperature was between -10° and -15° Celsius (14° to 5° Fahrenheit).

They entered the Nuuk flight information region and changed frequency to introduce themselves to Nuuk Information. They reported that they were descending from FL180 to 11,000 feet and inbound to the reporting point SIMNI on the coast of Greenland. SIMNI lies about 45 nautical miles south-west of Narsarsuaq.

They prepared for the descent. The weather at Narsarsuaq was good: light winds, excellent visibility, minimal cloud cover. The pilot began descending at 500 feet per minute, leaving the power set to 65%.

Then a faint smell appeared in the cockpit. Unusual. Maybe electrical.

Something was wrong.

The cabin altitude began increasing by a rate of 3,000 feet per minute. They were losing cabin pressurisation. Almost simultaneously, they saw a drop in oil pressure. Moments later, the CABIN ALTITUDE warning light illuminated, warning them that the cabin altitude was above 10,000 feet, meaning the pilots needed to guard against hypoxia.

As they were already descending at 500 feet per minute and below 15,000 feet. the pilot decided that they didn’t need to don the oxygen masks but should focus on the developing emergency. He made a PAN-PAN call, indicating an urgent but not life-threatening situation. This focuses local attention but is less critical than a MAYDAY.

PAN-PAN PAN-PAN PAN-PAN. We have an air conditioning problem and a low oil pressure indication.

In aviation, an “air conditioning problem” refers to the cabin pressurisation system, not temperature control.

The engine power dropped as the manifold pressure fell from 26 inches to 17-18 inches. The pilot pushed the throttle forward. Nothing happened. The pilot moved the mixture control forward to fully rich. The engine spluttered and almost stopped. The pilot quickly pulled the mixture back to where it was. The problem was clearly not a lack of fuel.

Now aware that they were dealing with a serious engine failure, the pilot pitched the aircraft for best glide at 90 knots and considered their situation. A minute had passed since the PAN-PAN call. He turned on the Emergency Locator Transmitter and updated ATC.

MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY. We have high rpm now and will try to make it to the shore.

The Danish Armed Forces Arctic Command heard the calls. They had a Royal Danish Air Force surveillance aircraft on patrol in the area and a Royal Danish Navy inspection ship nearby. Both were alerted to the situation and asked to help.

The Piper Malibu was descending through 7,000 feet when the propeller rpm increased to 3,000 rpm. Thirty seconds later, the oil pressure went to zero. Fearing catastrophical mechanical damage, the pilot pulled the mixture back to cut off the fuel and stopped the engine.

They were too far from the coastline to glide. They were out of options.

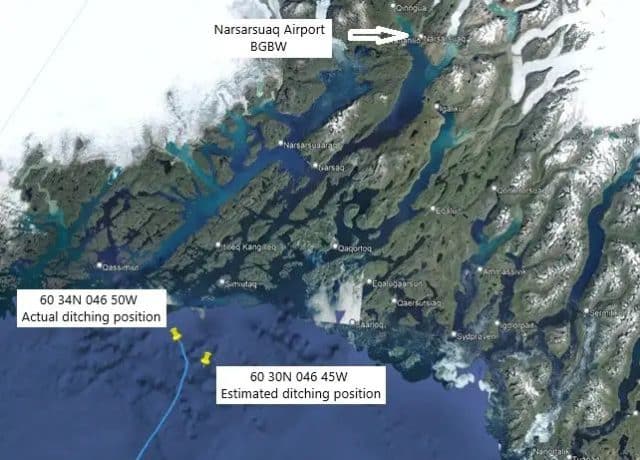

The pilot called Nuuk Information and gave approximate coordinates for their ditching: 60 30N 046 45W. 60°30′N, 046°45′W.

They zipped their survival suits up and tightened their seatbelts.

As they descended through 3,300 feet, the Royal Danish Navy Air Force aircraft spotted the stricken aircraft gliding north-east above a broken cloud layer. They lost sight of the Malibu as it descended into another layer of cloud at 1,700 feet. The surveillance aircraft flew towards the coastline so that they could descend and return to the last known position beneath the cloud.

At 700 feet above sea level, the Piper Malibu broke free of the clouds.

The pilot extended the flaps to 20° and flew as slowly as he dared before flaring directly over the low swells of the sea.

The Malibu touched the surface, bounced slightly, then settled again. They abruptly lost speed, “similar to a handbrake in a car,” they said later.

The Malibu came to a stop, wings level, floating on the surface.

You couldn’t ask for a better result.

The pilots released their seatbelts and opened the upper section of the aircraft door, which was still above the water level. They pushed the life raft through the door and inflated it, then tossed in the satellite telephone and a few personal items. Then they carefully made their way from the floating aircraft onto the raft.

The sea surface was calm with only minor swells. The depth of the sea at that location varied between 75 metres and 500 metres ( approximately 250-1,600 feet).

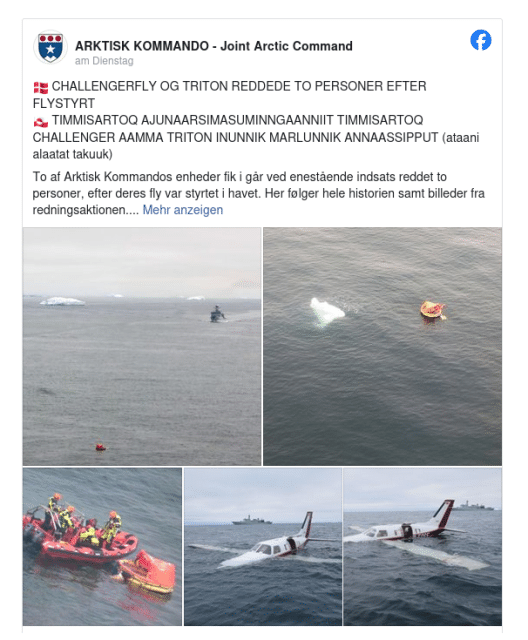

The surveillance aircraft spotted them seven minutes later at 60°34′N 046°50′W.

The Joint Rescue Coordination Centre Greenland led the search and rescue mission. In addition to the Danish Royal Navy, an Airbus H155 helicopter was redirected to the area.

Water slowly seeped into the aircraft.

The military aircraft circled overhead, so that the two men in the life raft knew that help was on the way. About twenty minutes after the ditching, the pilot was able to get through to the Nuuk Flight Information Center on the satellite phone. They reassured him that the Royal Danish Navy were already on the way with a rescue crew in a rigid-hulled inflatable boat.

The small boat arrived at 14:23, fifty minutes after the ditching, and recovered the pilots from the life raft.

The surveillance aircraft continued to circle, watching the Piper Malibu. It remained afloat for another hour before sinking beneath the surface.

The engine, a Teledyne Continental TSIO-520-BE2G, had been rebuilt in 2012. The recommended time between engine overhauls was 2,200 flight hours or twelve calendar years. When the two pilots purchased the Piper Malibu in 2019, the aircraft engine had about 600 flight hours. Between 2019 and 2024, the new owners put about 150 additional hours on the aircraft. During that time, there had been no engine troubles and oil consumption was very low.

The flight from Germany to Oshkosh for AirVenture took about 40 flight hours. Over the course of the journey from their home base to Oshkosh and onward to Goose Bay, the aircraft consumed one US quart of oil (just under a litre).

It is impossible to know for sure what happened to the engine, as it now rests at the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean. However, the symptoms described by the pilot tell us a lot. When he increased the mixture, the fuel-to-air ratio increased to a level that almost drowned the engine, which proves that fuel starvation was not the problem. Neither pilot noticed any increase in engine vibration, which would be expected if an engine component had failed, such as the crankshaft or the piston failure. The unusual “electrical” smell may have indicated an electrical fault, or it may have been vapour from an oil leak.

It seems likely that there was an oil leak, leading to the zero oil pressure indication before the pilot shut down the engine. Any oil that leaked must have burned off or evaporated before they ditched, as there was no oil on the water. This points towards a seeping oil leak rather than a sudden failure, which also fits the timeline from the first abnormal indication to the complete loss of oil pressure.

One possibility is that a turbocharger failed, which could account for the oil leak. Such a failure would cause a loss of compressed air to both the cabin pressurisation system and the engine induction system. The lack of oil pressure in the propeller governor would cause the low propeller pitch and high propeller rpms.

From the Danish Accident Investigation Board:

An engine failure during descent resulted in a ditching off the south-west coast of Greenland.

The AIB could not determine the exact cause of the engine failure, but it was likely due to a seeping oil leak.

A combination of the following factors made the accident survivable:

- The pilot declared an urgency followed by an emergency to ATS, and a nearby RDAF surveillance aircraft obtained visual contact with the gliding aircraft.

- The pilot successfully landed the aircraft on calm sea.

- The pilot and the passenger wore survival suits and carried a life raft on board, which they boarded upon safely evacuating the aircraft.

- After 50 minutes, personnel from a nearby RDN inspection ship arrived and rescued the pilot and passenger.

This video, released as a part of the report, compiles the footage taken that day. If you are reading in email, you may need to click through to view. It takes a moment to download.

We talk about holes in the cheese lining up but this was the opposite: everything lined up to allow for a happy ending.

It starts pre-flight, with the precautions taken by the pilots, wearing their full-body dry suits and having a life raft readily accessible. This meant that they were able to survive for the 50 minutes that it took for search and rescue to reach them.

The pilot declared an urgent situation followed by a Mayday, allowing the air traffic controllers to understand the situation and offer support while they were still in the air. Pilot skill also plays a role in this: successfully landing on the water.

There was a healthy dose of luck. The sea was very calm that day, with only minor swells. The Royal Danish Air Force surveillance aircraft and the Royal Danish Navy inspection ship just happened to be active in the area. The aircraft had enough time to visually identify the descending Piper Malibu and establish the site of the ditching. The inspection ship was close enough to be able to quickly respond to the situation.

Another factor was the RDN inspection ship’s decision to dispatch an RHIB which was able to reach them more quickly. This made it easier to recover the two men on the raft than it would have been in a helicopter, and both had been taken to safety by the time the ship arrived on the scene. The inspection ship took further video of the sinking aircraft, noting that there was no sign of oil or fuel spillage on the sea surface.

I love the fact that the Danish Accident Investigation Board made a point to focus on the positives, taking the time in their report to highlight all the things that went right.

You can read the final report on the Danish AIB site

Sylvia,

Another wonderful aviation story. Thank you so much.

Thank you for reading! And I love these happy endings, always.

Walter, I agree. This was a good outcome. This is where Sylvia excels: she does not necessarily concentrate on the crashes and accidents, she also gives other stories. From funny, banal, incredible to even the hilarious And of course also the Happy Endings. Talking about “Happy”: Happy New Year, Sylvia, and of course including your followers.

Reading this a few factors become clear:

I am often very suspicious of pilots who buy or fly very sophisticated aircraft, high performance and full of gizmos that they are neither qualified, nor able to handle properly.

Certainly not in this case: Needless to say, embarking on a transatlantic flight especially in a single-engine light aircraft, however advanced, is always a risky enterprise and I heard that some insurance providers, based on the aircraft and the level of experience of the pilot(s), either totally exclude this kind of operation entirely, or only allow it on condition that the flight be approved in advance by the insurers AND at an extra premium.

There is no doubt in my mind that the pilots in this case operated to a very high standard. One was obviously an airline captain, his ATPL and high logged time points to this conclusion.

They had prepared themselves well, with survival equipment to a high standard, and there was no reason to suspect a serious engine problem. The aircraft had apparently been properly maintained and serviced.

When the problem started to manifest itself, the crew did everything right. They did not panic, they alerted the authorities first by calling “Pan Pan, then, when the situation became more serious, they followed up with a Mayday call, and prepared for a ditching.

All calm and professional, getting the life raft and communication equipment ready.

The “luck factor” was present, yes, but I read this as a textbook example of how to do this properly AND SURVIVE.

The insurance will have to cough up, the pilots are blameless.

The explanation of a turbocharger blowing up and the subsequent loss of oil to the propeller governor seem to be the most plausible causes.

Now many years ago I delivered an American registered Turbo Commander to a dealer to be sold in the USA.

My time on type was minimal: perhaps 10 hours, a manual and a quick check-out by the owner. I took another pilot with me, he was good but had never been in a Commander, let alone fly it.

The route was from Weston, near Dublin, to Reykjavik, Narsarsuaq for refuelling and on to Bangor, Maine before delivery near Boston. Bangor is a compulsory entry- and exit point for smaller aircraft that enter or leave US airspace.

We had a comfortable fuel reserve, which was a good feeling because the weather over Greenland was bad. We flew high, I think FL 260 or 280, over 100% cloud cover. We encountered medium to severe turbulence. The weather at Narsarsuaq was not encouraging. The charts indicated (very) high terrain around the airport with a stepped NDB approach into a fjord. The airport was at the edge of the fjord.

As we came at the first “step”, still maybe 4000 feet high, we checked the approach charts carefully again. The approach mandated a high approach angle, I cannot remember but it may have been 5 or 6 degrees. We had intermittent ground contact but we could put the birdie down without problem.

A few weeks before the flight the aircraft suffered a loss of pressure in one of the landing gear oleos. This was supposed to have ben fixed, but it sat down again in Reykjavik. After consulting the owner, we decided to continue. The gusty weather made a “soft” landing difficult, but we had no further problems. Nor a ready budget for a quick repair job.

It was a strange feeling, departing from a small aerodrome in Ireland, only in use by private aviation and a flying school, and read back an “oceanic” ATC clearance.

The Inuit people who refuelled us in Greenland were friendly and efficient.

The only other time when I landed in Greenland was when delivering the brand-new Citation that my then employer had bought; the pilot who flew with me for the first trip through South America, and onwards to Amsterdam, was a retired USAF colonel and he had arranged for permission to land at USAF base Sondrestrom Fjord, now a civilian airport.

Greenland and the USA have been friends and allies for a century, it is to be hoped that the current dispute will be settled amicably.

I’m jealous that you got to see Narsarsuaq! I am already biased against the new airport, just for being new.