83ft above the sea at night and no investigation?

I’m often asked about government cover-ups and the “real story” behind well-known commercial incidents. Generally, it’s easy to give an optimistic answer. Most investigations carried out by most of the accident investigation bureaus are top class: thorough and honest and with a detailed report which allows us, the outsiders, to check their work.

This case, however, makes me extremely uncomfortable. Although there is no direct evidence of a cover-up, it was certainly at best incompetently handled by the operator and the Norwegian CAA. In a perfect world, a situation like this should never arise. However, I’m pleased to say that with the investigation and reporting atmosphere around the world, it is at least possible to spot when it goes awry. In this instance, Aviation Herald is doing a brilliant job of pushing for answers about a serious incident which had been dismissed as not requiring an investigation at all.

Let’s start with the facts that everyone agrees on.

The date was 2nd December 2010. The aircraft was a de Havilland Dash 8-100 operated by Widerøe. It departed on a domestic Norwegian flight from Bodø to Svolvær, scheduled as flight WF-814 with 38 people on board. The weather was bad. The captain was the Pilot Flying and the first officer was the Pilot Monitoring.

Svolvær runway is 01/19. The aircraft was turning base for 19 for its approach to Svolvær when something went wrong. The airspeed dropped and the stick-shaker activated. The engines were accelerated to maximum power. The flight crew agreed to abort the approach and diverted to Leknes, where they landed without incident. From Leknes, they returned to Bodø.

The captain reported the occurrence to the operator. Both engines were checked for over-torque before the aircraft was returned to service, which should have been done before returning to Bodø. The chief pilot met with the captain and the first officer to collect information on the occurrence. As a part of this meeting, the first officer requested a copy of the print-out from the flight data recorder. Widerøe’s operating report stated that the aircraft went around at Svolvær because of turbulence and a downdraft, while on left base to runway 19. It also noted that the reports from the captain and the first officer did not agree.

Widerøe forwarded the captain’s report to the Norwegian Civil Aviation Authority. The Norwegian CAA filed the occurrence as an “incident” and did not refer it to Norway’s Accident Investigation Bureau (AIBN) for an investigation.

So the obvious initial issue is that the “incident” as reported by the captain did not match the events as related by the first officer. Of note is also that the first officer clearly felt strongly enough about this discrepancy to request a copy of the Flight Recorder data. It was two years later, when he left the operator, that he realised that no investigation had taken place. He also discovered that only the captain’s report had been forwarded to the CAA and based on the Captain’s version of events, the CAA did not believe it merited an investigation.

On the 17th December, 2012, the first officer phoned the AIBN and submitted his initial report directly to them, along with the print-out from the flight data recorder.

As a starting point, let’s look at what the print-out from the flight data recorder demonstrates. Aviation Herald posted a summary of the most important points:

- The stick shaker activated, which is a warning for the pilot that the aircraft is flying too slowly and is at risk of a stall

- The aircraft was at 400 feet above sea level when the stick shaker activated

- Eight seconds later, the aircraft stopped its descent. It was 83 feet above sea level

I need to stop there. The aircraft was not yet established on final approach. It was 83 feet (25 metres) above the sea. This alone seems to be a clear case of a serious incident.

To put it into perspective: their height above sea level was less than the wingspan of the Dash 8. It was less than the height of New York City’s Christmas tree. It was a hell of a lot less than the height they needed to be safe.

Anyway…

- The average rate of descent was 2,377 feet per minute; however, with an initial vertical acceleration of 0.75G and a final vertical deceleration of 2.7G, it’s likely that the maximum vertical rate of descent probably reached 3,500 feet per minute less than 150 feet above the sea.

- In the eight seconds while the aircraft was descending, the pitch angle of the aircraft increased by 10 degrees nose up, then nose down by 15 degrees and then back to 10 degrees nose up.

- While the aircraft was being pulled out of the descent, it experienced over 2.7Gs, which exceeds the structural limit of the Dash 8

- Both engines were over-torqued, reaching 118% and 120% of torque over a period of 35 seconds.

Without any other information, the information from the flight data recorder should have triggered an investigation.

Obviously, the next question is what happened in the cockpit? Both pilots agree that the captain was flying while the first officer was monitoring. The weather was bad. They were turning left onto base for their approach, which meant that the airport lights were behind them. It was completely dark and neither the horizon nor the sea below were visible.

The captain said he first noticed something wrong before he initiated the turn. There was a significant drop in airspeed and the aircraft started buffeting, a warning of an impending stall. He said that at the same time, the first officer called out “check speed”.

The captain said that he responded immediately: he pushed engine power to full and pitched up; however the aircraft continued to lose speed and to descend. He said that it felt like the aircraft was falling or being pushed down.

He pushed the control column forward to gain airspeed and prevent the stall. When he pulled the stick back again in order to climb out, the aircraft’s stick shaker triggered. He eased off to build up more speed and saw the red obstacle lights in front of him. He recalls looking at the altimeter and that it showed them as approximately 300 feet (90 metres) over the sea. He focused on one of the red lights and stayed low, in order to build up speed. It worked and he initiated the climb. He saw that they would pass over the light at a safe altitude. After he gained sufficient speed and the aircraft started to climb, the first officer unexpectedly took control. He decided not to oppose this but left the first officer to climb away.

The general facts are the same in the first officer’s version, however the actions taken by the captain are very different. The first officer said that he was monitoring the instruments when he called for the captain to “check speed” during downwind. Then again, as the captain had initiated the turn, he called out “check speed”. He felt that under the circumstances, the corrections made by the captain were too small. As they turned in for final approach, the stick shaker triggered. He remembers that he was startled by the shaking. He was prepared to perform corrective measures but the captain did not make the expected call out and reaction. Next, the nose of the aircraft made a significant dip. He said that he “stared straight down onto the black sea” and saw a red light on a islet below.

The first officer said that he grabbed the control wheel and pushed the engine controls all the way until they stopped (approximately 118%). He remembers pulling the stick back with both hands and believed that they were still likely to crash into the sea. The aircraft started to climb. Once at a safe height of 3,000 feet, the first officer and the captain agreed that the captain should resume his role as pilot flying.

They diverted to Leknes for a safe landing and then continued to Bodø to debrief there.

Based on the FDR data, we know as fact that the aircraft stopped its descent at 83 feet (25 metres) above the sea and, eight seconds after the stick shaker activated, began to climb again.

The first officer wrote:

A total of 38 people were on board of flight WF 814 on Dec 2nd 2010. The luck and coincidences that night averted that this evolved to be the worst accident in Widerøe’s history.

However, he did not receive a reply to his direct submission for six months. It was the 14th of June, 2013 when he received a formal response from the AIBN, signed by the director as well as the Aviation Department Head.

The accident investigation did not find the basis for a change of the status of the event from incident to serious incident

There is a significant discrepancy between what has been initially reported to the CAA and how you describe the event today.

The situation was not seen critical as reported by [Svolvær] Tower.

The letter went on to state that although, the AIBN does get contacted by passengers reporting “unpleasant” experiences, they had not received any reports from the passengers on the flight that day.

This does not necessarily mean that the passengers did not experience the event as scary. Such passenger reports are a safety net for the AIBN in case reporting requirements are not being met. Widerøe’s last internal event report and conversation with you, cabin crew and others in Widerøe suggest, that a lot could have been done better after the event had occurred. The long time since the event took place would hamper an investigation by the AIBN.

They also confirmed that the print-out from the flight data recorder matched that submitted by the airline in 2010. In the end, they stated that the operator (Widerøe) had room for improvement for occurrence reporting and should ensure that pilots were aware that they could independently report to the CAA and the AIBN.

There does not appear to have been any mention of the conflicting reports from the captain and the first officer, nor is there any mention that the report from the first officer was missing from the operator’s report.

And so, the occurrence was deemed again not to need an investigation – at least until this year.

In February of 2015, Norwegian newspaper Nordlys reported that an aircraft had lost height on approach to Svolvær and was recovered at 27 metres over the sea, accompanied by charts based on the read-out from the flight data recorder. The mainstream Scandinavian media didn’t pick up on the story.

On the 16th of March, the AIBN reported they had (finally) opened an investigation into the occurrence. They stated that flight WF-814 was in the final stages of the approach to Svolvær when the airspeed abruptly slowed and the stickshaker activated. The crew aborted the approach and diverted to Leknes where a safe landing occurred.

On the 5th of June, a source contacted the Aviation Herald. The source told Aviation Herald that the aircraft had entered a full stall on visual approach to Svolvær.

The aircraft was turning base when the airspeed sharply dropped and the stickshaker activated. The engines were accelerated to maximum power available, the pitch continued to increase until the aircraft entered full stall however and the captain basically froze. The first officer took control of the aircraft, pushed the nose down, managed to recover the aircraft from the stall and pulling +2.7G arrested the descent at 25 meters AGL. The aircraft subsequently diverted for a safe landing.

Following the occurrence the captain provided a report about the occurrence to the safety department of the airline which prompted both engines to undergo checks for overtorque before the aircraft was returned to service. Our source said: “The captain drastically understated the severity of the situation. The AIBN cannot investigate what it does not know.” The first officer left the company and joined another airline.

Aviation Herald verified the information received, including the FDR data, and contacted the Statens Havarikomisjon for Transport (SHT, includes the AIBN) seeking clarification. They asked specifically why the investigation had not been opened in 2010. They also stated that they planned to release the story on the afternoon of 18 June 2015.

On the morning of 18 June, they received a statement from the Chief Inspector of the Aviation Department of the AIBN.

Yes it is correct that the mentioned aircraft was involved in an incident on December 2010. This incident was reported, both by the captain, the company and the air traffic controller, as an incident to the CAA and thus never reached the accident investigation board of Norway (SHT). Two years later the SHT became aware of the incident. Based on the information at that time the SHT chose not to reclassify the incident as a serious incident. This together with the fact that the incident had occurred two years ago the SHT chose not to open an investigation. It is also true that it was public expectation that made the SHT to open an investigation this year. This is a full investigation, as any other. The available information from FDR is analyzed in cooperation with Bombardier. At this stage in the investigation, the SHT will not release any information from FDR. Based on this we are sorry to say that we will not confirm your assumptions. The SHT expects the report to be public by the end of this year.”

Aviation Herald’s information is that the captain submitted a report of a stick shaker activation and stated that the aircraft lost some height but never descended below 300 feet. The captain’s report also included the fact that both engines were overtorqued well above engine limitations and that the period of overtorque may have lasted up to 20 seconds. Their sources told Aviation Herald that Widerøe decided that, as they could not reconcile the two conflicting reports, they decided to only forward the captain’s report to the Civil Aviation Authority.

On 7th July 2015 Richard Kongsteien, Vice President Public Relations of Widerøe, wrote to Aviation Herald:

Because the incident is under an investigation, we will not comment on the story apart from saying that your insinuations that Widerøe deliberately withheld information from the authorities is utterly wrong, and contradicts every safety policy we live by in our company. A clerical filing error was made when one of the reports was delivered to us some time after the incident. This is something we are sorry happened. The error was discovered by us, and corrected by us. We look forward to the closing of the investigation by the authorities, which we hope will end all rumors and speculations about this incident.

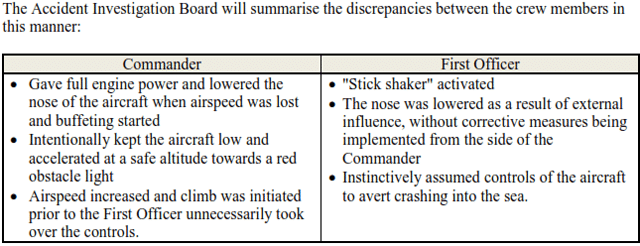

The Norwegian investigators now definitely have have both crew member reports along with Widerøe’s operational report and the FDR data. They released a preliminary report on the 21st August in which the occurrence is reclassified as a serious incident: Preliminary report on serious aviation incident at Svolvær airport Helle, Norway 2 December 2010 involving Bombardier DHC-8-103, LN-WIU operated by Wideroes Flyveselskap AS | aibn

The preliminary report states that, based on the FDR data, the most probable time when the control wheel was taken over was approximately two seconds before the engine power was increased beyond maximum. This supports the first officer’s versions of events, however they go on to say that, as a result of inertia, the captain could have already implemented the measures that the first officer was waiting for.

The aircraft lost approx. 270 feet over the course of 8 seconds. Preliminary analyses of the graphs from the flight recorder indicate that during these seconds, the aircraft was exposed to significant external influences. The Commander’s reaction and correction of both attitude and engine power seem to have prevented stalling. The subsequent pull-up most likely prevented a crash into the sea.

It is correct that the nose was below the horizon and that the aircraft was still losing altitude when the engine controls were moved completely forward until stop, but at the time AIBN believes the First Officer intervened, the stick had already been moved significantly back and the tendency had turned.

The report mentions the visual conditions (bad weather and in darkness) which are typical for creating spatial illusions. However, the report concludes only that the crew successfully averted crashing into the sea after being exposed to a major wind shear at low altitude.

For further reading, I recommend the sequence of events and the Aviation Herald’s investigation on the incident page:

Incident: Widerøe DH8A at Svolvær on Dec 2nd 2010, aircraft rapidly descended on base turn, recovered at 25 meters AGL

The first officer was the only person to push for an investigation; this fact alone has me firmly on his side. I find it incredibly worrying that the AIBN don’t seem be dealing with the issue at all that a serious incident was not reported, instead focusing on explaining why it was not their fault that they didn’t respond in 2012. Quite frankly, I would be pushing back hard at the CAA and Widerøe for not informing the AIBN, rather than some nonsense about how none of the passengers reported it. That’s not their job.

I hope that the final report takes on the issues without prevarication or excuses. A good investigation does not seek to allocate blame but to understand how the situation happened and how to avoid it happening again. In this case, they need not only to consider the incident but also the response.

An excellent article, Sylvia.

As soon as I had read beyond the first lines, one word nearly appeared in my mind like in front of my eyes, lit like a beacon.

It read: VERTIGO !

The Skandinavian airlines in general have an excellent standard of operation. I once sat in the jumpseat of an SAS MD 81 and was very, very impressed by the total professionalism of the crew.

But on occasion small, local operators seem to drop a few notches.

The training standard may be OK, even good but a lot depends e.g. on the relationship between a particular crew member (captain) and the Chief Pilot of Fleet Captain. I know from experience how hard it is to be forced to end the career of a colleague, let alone if (s)he is a personal friend.

I think I have related in an earlier comment how a F/O found it necessary to refuse to fly with a certain captain and I was dispatched in a hurry to take over. Both the F/O and the ground crew agreed that the captain was behaving in an incoherent manner, had trouble walking in a straight line and smelled of alcohol. But nevertheless, some other captains shunned him.

I agree: By the look of it, the F/O has to be commended for his actions and refusal to give up. In any serious airline he should soon if not already be on his way to command.

A friend of mine, in his capacity of JAA qualified TRE/IRE once was hired to do proficiency checks in a small local airline.

On one flight, he failed a captain during a line check following an incident (I will not comment further, I have it only as hearsay).

But, my friend not being a permanent member of staff, the Chief Pilot overruled him and reinstated this captain without any repercussions.

The same captain, some months later, was involved in another incident similar to the first but this time it ended with the aircraft being written off. Fortunately without loss of life.

Judging from what you wrote here, Sylvia, in my opinion this was a very serious incident that without intervention from the F/O could just as easily have led to a loss of the aircraft and the loss of life of everyone on board.

Let me just add: If the cause of this incident had been caused by serious low-level windshear, it would have been unlikely that the two pilots had reported such a different version of the event.

The investigators might be well advised also to look into the personalities and personal relationships between crew members in this airline.

Clearly CRM issues here. I’m really, really hoping that the AIBN redeem themselves here with a thorough final report, although their prelim doesn’t fill me with confidence.

Sylvia, you always do excellent research and back it up with official reports. But even so, again it must be noted that my comment is based only on your article.

This is serious stuff. Much worse than just a CRM problem.

There was a very serious incident which only by sheer luck did not become an accident.

If I understand what happened:

The captain, possibly due to vertigo, lost complete control over the aircraft.

The co-pilot took over and this action prevented a total loss of the aircraft and it’s occupants.

The incident would possibly have warranted the F/O relieving the captain of his command but the hierarchical structure in an airline makes this a decision so serious that very few co-pilots will resort to this measure of last resort unless there is a clear case of incapacitation. So the captain resumed his role as pilot flying.

The rest is murky. The engines were overtorque’d and the airframe was stressed possibly beyond the admissible limits.

The pilots sent in contradictory reports about the incident, the airline did a check on the engines and returned the aircraft to service.

There seems to have been very little reference made to the FDR which would have answered quite a few of the questions that this incident should have generated.

The airline accepted the captain’s version, brushed the whole affair under the carpet and the authorities – unusually – did not seem too worried. The whole affair came to light much later and by accident.

The only person who comes out clean is the co-pilot.

All this would make me wonder if Wideroe is a safe airline to fly with.

The FDR is referenced as the print-out which was submitted to the CAA, the Norwegian Accident Board, the press and Aviation Herald. All four documents have been confirmed to be the same. The prelim report basically says that based on the FDR data, they believe they can tell when the FO took control and that they are not convinced it was necessary at that time (i.e. the Captain took action and the FO was reacting to inertia). But based on the fact that that the Captain’s retelling doesn’t match the FDR data and the FO’s does, I really feel that they should be looking at this a bit closer.

But yes, I agree that the non-response of the authorities and Wideroe brings up a clear safety issue.

I do not think that we disagree, Sylvia.

The complacency that seems to have been displayed by various parties involved in the investigation makes for disturbing reading.

Hi

Not trying to be clever here but can would it be possible to stop calling a preventable crash an accident as the word accident implies non-fault. As we know most incidents are preventable. Even the police now refer too vehicle collisions (or crashes) as incidents Police Traffic Officers are now referred to as ‘Crash Investigators’ instead of ‘Accident Investigators’

Just saying hope no one minds

I certainly don’t mind. However, within crash investigation I don’t think accident implies non-fault – at least not in the UK. An accident is defined as damage done to person or vehicle, whereas a serious incident is one where the likelihood of an accident was high, even if no one was injured. More here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/definition-of-aircraft-accident-and-serious-incident/definition-of-aircraft-accident-and-serious-incident

Difficult sometimes to work out the semantics, true enough.

And it is sometimes even more difficult to understand why the press makes a huge story out of a very minor incident.

Like to-day when a lot was made in the press in Ireland about an “emergency” landing of an Aer Lingus B757 at JFK.

A lot of whipped-up air. According to the news items, the aircraft had suffered a hydraulic leak shortly after take-off.

Anybody even slightly familiar with modern aircraft knows that the aircraft will have a second hydraulic system and, “to be sure to be sure”, an emergency system to provide at least the basic requirements, like getting the wheels down and the brakes operating once back on terra firma.

Of course the aircraft had to circle for a while to get through the emergency checklist and confer with the airline’s technical and operational experts. And it may have been necessary to dump fuel.

In such a case the airport emergency services will ALWAYS have fire engines along the runway. It is all well-rehearsed and nearly routine, even if the rehearsals of the crew took place in a simulator.

Against that read about the incident Sylvia threw in her (our?) forum for a discussion, which had not made any news headlines at all.

The captain did one thing right: he relinquished the controls to the first officer. If he hadn’t, this article might very well have been about the “Dash 8 that crashed into the sea!”

Not quite, Andrew.

The way I read it, the captain did not really “relinquish the controls”. To me it seems that the F/O did the only thing open to him: he took over, nearly instinctively when he realized that the captain (pilot-flying) was disorientated, had “lost the picture” and was about to crash.

During that period, the F/O was in fact in command of the aircraft and must be commended for his action.

Once the situation was brought under control, the captain took command again.

At that period of time, technically speaking, the F/O would have been fully justified relieving the captain of his command but, as I already explained, this is a very major step especially if the captain is not really medically incapacitated.

The seriousness of the incident is underscored by the fact that the captain tried to put the facts in a different light and actually did get away with it – until recently. Witness the different reports from the two pilots and the fact that the FDR read-out supports the version as submitted by the F/O.

Again: the above is my interpretation of the facts as presented by Sylvia.

But Andrew is quite right when he mentions: “if he (the F/O) hadn’t (take over), this article might very well have been about the ‘Dash 8 that crashed into the sea!'”

When I say he relinquished the controls, I mean that he did not try to overrule the first officer from taking them. He didn’t try to take them back.

I think we can certainly agree that the first officers actions were what saved the plane. This is one of the few situations where we would be entirely justified in describing the first officer, rather than the captain, as a hero!

I would have some sympathy for the captain for misjudging the situation, (after-all, we all make mistakes) but for the fact that he tried to misrepresent it and he was believed. One might even go as far as to argue that he was abusing his power by doing that! I mean, unless he genuinely still believes that is wasn’t a major incident? But, how could anyone think that?

Andrew,

I have Sylvia’s entry to go by so my reactions are entirely based on what she wrote about the incident.

But, from my perspective as a former commercial pilot and airline captain with about 22000 hours flying experience my assessment is that the captain was not in control of the aircraft nor of the situation.

Vertigo is a nasty thing to happen. It can incapacitate a pilot suffering from it and I still think that vertigo is at the root of this incident.

A visual approach at night and in poor weather are conditions that present a high risk for vertigo. The captain was “turning base”, so the aircraft was probably banking. An added factor.

I still clearly remember a case early in my career in the early ‘seventies. I was flying single crew into Frankfurt in a Cessna 310. It was early evening, hazy and the sun setting as I was on the approach for runway 25R. In these conditions the visibility into the sun can be very low whereas away from the sun the vis may be miles and miles.

I was passing through about 800 feet and was getting visual so I decided to continue on a visual approach.

There was – perhaps still is – a motorway crossing the threshold, but at an angle with the runway. From my perspective it gave me the impression of a false horizon from a high point in the left of my field of vision to the bottom on the right.

Vertigo was virtually instantaneous.

Fortunately, I had enough experience to realise what was happening.

I was still on the ILS. I immediately put my head down, went back on instruments and continued on an instrument approach.

The Wideroe flight was not on an instrument approach. Solvaer is a small regional airport. I do not know it, but I doubt that is has an ILS.

The incident was nearly set-up from the beginning: A short runway, it was dark, the weather was bad (read the report). An experienced pilot, familiar with the situation, should have been alert and ready to abandon the attempt to land at this airport.

So Andrew, having tried to analyse the incident I think that you are far too kind. The captain had lost it and was not in a state of mind to even contemplate to take back the controls until well after the F/O had saved the aircraft from a near-certain crash.

The captain misjudging the situation? I have left aviation some 7 years ago but if I had been in charge of an airline when such an incident occurred the captain would have been dismissed.

Harsh? Certainly but aviation can be very harsh and unforgiving.

Why and how this captain was allowed to get away with it for such a long time is another subject, but Wideroe would not be an airline I would like to travel on.

Of course, my judgement has been based on what has been presented here and some facts might have been omitted. On the other hand, Sylvia has already proven to present excellent and unbiased write-ups.

The AIBN has released the translation of the report at the end of 2016.

https://www.aibn.no/Aviation/Published-reports/2016-11-eng

It states:

“Based on the available facts, the Accident Investigation Board has not been able to determine neither which pilot did what, exactly when, and in which order, nor the effects of each action, seen in isolation. It has therefore not been possible to draw any solid conclusions about the significance of the actions of the first officer.”

They forgot to add “during the incident”. The significance of his actions after the incident is rather hard to overlook. There would be no investigation and no report if he didn’t insist.

A report was indeed released, dated 2015 but apparently released in 2016. There seems to be some dispute about the English language content versus the Norwegian language content.

The excellent AVN article linked in Sylvia’s article was appended several times through 2016 but no later information was available in the English language site.

Sylvia, do you monitor the old post comments for updates? I am curious what the final outcome of the investigation.

PS AVN Stated that the first officer stopped flying for the airline after he lost his medical card. That’s curious.

I do monitor old posts for comments! I will look into this and see if I can find out any more.

Thank you. The AVN article was very informative but it was last updated 2016.

The Accident Investigation board and CAA were given a chance to redeem themselves in 2015 but it sounds from the article that they did not cover themselves with glory on this one.