$10,000 Reward for Aircraft Mechanic

This week, the FBI announced a $10,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of a man who once worked as a mechanic at SabreTech, the airline maintenance company at the centre of the tragic loss of ValuJet flight 592, which crashed into the Florida Everglades on the 11th of May 1996.

It’s not often that an old aviation incident makes the news over twenty years later so I was immediately intrigued. To understand what the news is about, though, we need to know the details of the disorganisation and mismanagement which led to the violent fire and crash of the flight ten minutes after take off.

On that day, ValuJet flight 592 was a Douglas DC-9-32 which had arrived from Atlanta late after unplanned maintenance. The flight was due to depart Miami to fly back to Atlanta at 13:00.

There were five crew and 104 passengers listed on the manifest. Actually, there was an additional passenger, a four-year old boy travelling with his family who was also not included on the weight and baggage calculation. When the aircraft departed, however, there was a total of 110 souls on board.

The cargo for the flight was a combination of baggage, mail and company-owned material. According to the shipping ticket, the company-owned material consisted of

- two main gear tyres and wheels

-

a nose gear tyre and wheel

-

five boxes listed as Oxy Cannisters – ‘Empty’

The lead ramp agent showed the first officer the shipping ticket and asked for approval to load the company-owned material into the forward cargo compartment, which he got.

The DC-9 departed Miami just over an hour late at 14:04. A few minutes after departure, with the aircraft at 10,000 feet and travelling 260 knots, the cockpit voice recorder recorded an unidentified sound and the voice of the captain asking, “What was that?” The timestamp was 1410:03

He said, “We got some electrical problem” followed by “We’re losing everything.” As he told the first officer that they needed to go back to Miami, the CVR recorded voices shouting fire in the background. The first officer contacted ATC but as they started their turn and descent, the cockpit was already full of smoke and a cabin crew members voice could be heard shouting that they were “completely on fire.”

The first officer transmitted that they needed the closest available airport. There was an unintelligible transmission while the controller tried to offer details of a closer airport. That was the last thing heard from the DC-9. ValuJet 592 crashed at 1413:42, less than four minutes after the strange sound.

Two men out fishing saw the low-flying aircraft in a steep bank. The nose was dropping and by the time the it struck the ground, the plane was almost vertical. Then it crashed with a great explosion, followed by a huge cloud of water and smoke. The Atlantic gives the following account of their phone call to emergency.

The caller said, “Yes. I am fishing at Everglades Holiday Park, and a large jet aircraft has just crashed out here. Large. Like airliner-size.”

The dispatcher said, “Wait a minute. Everglades Park?”

“Everglades Holiday Park, along canal L-sixty-seven. You need to get your choppers in the air. I’m a pilot. I have a GPS. I’ll give you coordinates.”

“Okay, sir. What kind of plane did you say? Is it a large plane?”

“A large aircraft similar to a seven-twenty-seven or a umm … I can’t think of it.”

“Yes, sir. Okay. You said it looked like a seven-twenty-seven that went down?”

“Uh, it’s that type aircraft. It has twin engines in the rear. It is larger than an executive jet, like a Learjet.”

“Yes, sir.”

“It’s much bigger than that. I won’t tell you it’s a seven-twenty-seven, but it’s that type aircraft. No engines on the wing, two engines in the rear. I do not see any smoke, but I saw a tremendous cloud of mud and dirt go into the sky when it hit.”

“Okay, sir.”

“It was white with blue trim.”

“White with blue trim, sir?”

“It will not be in one piece.”

It was immediately clear that there had been an intense in-flight fire and from the wreckage it was clear that it started in the forward cargo hold. This hold was a “Class D compartment” which meant that at the time, it wasn’t required to include fire suppression units nor smoke detectors as the hold was airtight – so theoretically, any fire that started there would burn itself out quickly. Effectively, Class D compartments used oxygen starvation as a built-in fire suppressor.

However, the hold had been loaded with the five boxes of oxygen generators. Although the shipment was labeled ’empty’ (in quotes), they weren’t actually empty.

It turned out that a few months earlier, ValuJet had purchased three MD-80 jets a few months earlier and the maintenance contact was given to SabreTech Corporation. The maintenance included the inspection of the oxygen generators on the planes, of which many were past their expiration date. ValuJet decided that all of the oxygen generators should be replaced and directed SabreTech to do so.

SabreTech removed 144 oxygen generators from the MD-80s, of which six were expended. The rest of the cannisters were still active*. The oxygen generators use a chemical reaction to flow the oxygen to the reservoir bags of the mask. As a side effect of this exothermic reaction, the generators get very hot. When operated at normal room temperature, the outside of the oxygen generators can reach up to 547°F (286°C).

- Edit: I’ve rephrased this because, Tammy Cravit points out in the comments, they do not hold oxygen. The generators contain an oxidizing chemical, such as sodium chlorate. Burning the oxidizer produces oxygen, along with a great deal of heat.

Normally, if an oxygen generator is transported, it is fitted with a safety cap which disables the pin and stops the oxygen generator from, well, generating oxygen. However, SabreTech didn’t supply the safety caps that day so, as far as the mechanics were concerned, the caps weren’t available. The oxygen generators were tagged with green “repairable” labels, although there was no intent to use them again. It’s not clear whether the maintenance staff understood this but one thing is certain, they knew that the oxygen generators were not empty and thus that they needed safety caps. But, as one SabreTech employee said, they’d been working 12-hour shifts and 7-day weeks and were under pressure to get the job done. The mechanics added reason for removal written near the bottom of the green tags: out of date or expired and collected them into five cardboard boxes so they could be moved out of the way. One of them remembers noticing that the job hadn’t been finished, but he was reassured that the problem would be taken care of “in stores”.

Two Sabretech mechanics signed off the work cards for the MD-80 maintenance once the new generators were installed, confirming that the safety caps had been fitted onto the old ones, even though they haven’t. As far as they were concerned, the oxygen generators were ready for disposal and, more importantly, they had finished the job before the deadline.

The boxes were moved to SabreTech’s shipping and receiving area and left in the ValuJet section. They appear to have been abandoned; there was no record of what was in the box or that the contents were hazardous material.

A few days later, a stock clerk was told to tidy up and the boxes sitting on the floor were obviously in the way. They belonged to ValuJet so it made sense to send them to the company’s headquarters in Atlanta. This was something he’d done before and did not need to get approval for. He quickly repacked the oxygen generators with bubble pack, labelling the boxes as ‘aircraft parts’.

He saw the green labels, which he knew meant unservicable, while red meant ‘beyond economical repair’ or ‘scrap’. So he presumed that the oxygen generators were were empty and needed refilling. He never read the ‘reason for removal’ text on the tags.

He listed the contents as Oxygen Cannisters — ‘Empty’ and handed the boxes and nine tyres to a SabreTech driver to deliver them to the ValuJet ramp area.

There, a ValuJet employee signed for the items and stored them in a baggage cart, with no idea that he’d accepted five boxes of hazardous material.

On the day of the crash, a ValuJet ramp agent loaded the rubber tyres into the class D cargo hold and then stacked boxes of oxygen generators — loosely packed with no safety caps — on top. He heard a clink sound as he moved one of the boxes and he could feel objects moving inside the box. He placed the boxes on top of a large tyre circling a smaller one. They weren’t wedged in but he had no idea that it mattered. He didn’t see any reason to believe there was dangerous cargo in the box.

The first officer had been trained to watch for hazardous materials and knew that they should not transport hazardous materials such as working chemical oxygen generators on a passenger flight, even if they had been capped. But again, there was no reason to open the boxes; as far as he knew, they had a few old tyres and some empty canisters. The flight was already almost an hour late departing and they needed to get moving. He probably never gave it a second thought.

From here, it was only a matter of time until one of the improperly packed oxygen generators ignited.

We’ll never know exactly what happened but it seems likely that an oxygen generator was activated while the boxes were being loaded (maybe even at the moment of the clinking sound) or, at the latest, during the vibrations of the take-off roll.

The NTSB recreated the set up with a test hold. About ten minutes after they ignited an oxygen container, the hold reached 2,000°F (1,100°C). Another test reached 3,000°F (1,650°C). A main gear tyre ruptured sixteen minutes after the first ignition.

The sound of the gear tyre rupturing is probably what the captain heard in the cockpit, the first sign that anyone had that things were not right. By now, the temperatures in the hold were already fantastically high; there was no way that the fire could be contained. It was only seconds before the fire breached the cargo compartment ceiling, filling the passenger cabin with smoke.

The left-side floor beams melted and collapsed, probably taking out the control cables on the captain’s side. As the fire continued, the flight controls possibly failed completely or the flight crew may have been incapacitated by the smoke and heat in the cockpit in the last seconds. Whatever the cause, ten minutes after take off, the aircraft was no longer under anyone’s control and smashed into the ground.

The NTSB investigation pointed the finger serious failings of ValuJet airline and the airline’s maintenance company, Sabretech, both of whom failed to follow regulations regarding the transport of hazardous materials by air. The FAA also came under fire for not adequately monitoring airlines.

From the conclusion of the final report:

The Board determined that the accident was caused by: (1) the failure of SabreTech (a contract maintenance operation in Miami) to properly prepare, package, and identify inexpended chemical oxygen generators before presenting them to ValuJet for transportation;

(2) the failure of ValuJet to properly oversee its contract maintenance program to ensure compliance with maintenance, maintenance training, and hazardous materials requirements and practices; and

(3) the failure of the Federal Aviation Administration to require smoke detection and fire suppression systems in Class D cargo compartments.

Contributing to the accident, the Board found, was the failure of the FAA to adequately monitor ValuJet’s heavy maintenance program and responsibilities, including ValuJet’s oversight of its contractors, and SabreTech’s repair station certificate; the failure of the FAA to adequately respond to earlier chemical oxygen generator fires with programs to address the potential hazards they posed (the Board cited 6 cases in the 10 years before the ValuJet accident involving fires caused by oxygen generators); and the failure of ValuJet to ensure that both ValuJet and contract maintenance employees were aware of the airline’s “no-carry” hazardous materials policy and had received appropriate hazardous materials training.

The US Attorney’s Office filed 24 indictments against Sabretech and three of its employees for various violations of federal regulations regarding the transportation of hazardous materials. This was the first criminal prosecution over a U.S. airline crash. The charges included conspiracy to make false statements to the FAA and false statements in aviation maintenance records. The three SabreTech employees were the company’s Director of Maintenance and the two mechanics who had signed off the work order for the removal of the oxygen generators.

Both of the mechanics were specifically charged with falsifying work cards because the cards they had signed indicated that safety caps had been installed on the oxygen generators.

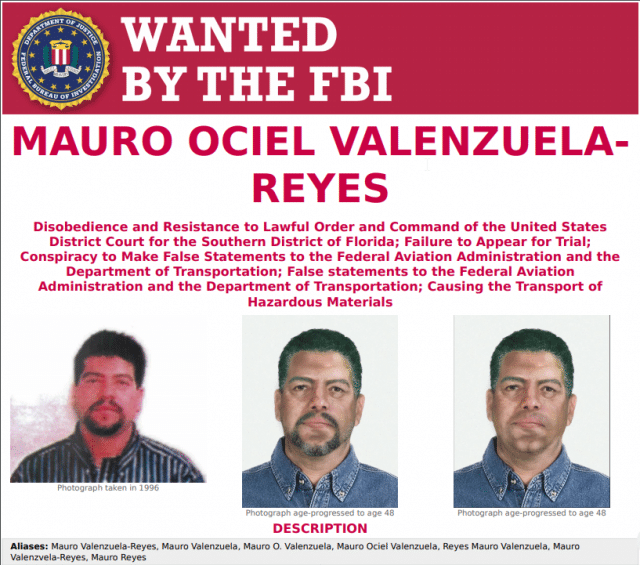

But before the trial took place, one of the mechanics, Mauro Ociel Valenzuela-Reyes, at the time more commonly known as Mauro Valenzuela, disappeared.

He may have fled the country back to Chile, where he was from, or he may have remained in the US under a false identity to be close to his family and children. All that is known for sure is he was never seen again.

The trial lasted several weeks. The SabreTech defence argued that, although the mechanic hadn’t ensured that the safety caps were used before signing off, he couldn’t possibly have known that someone would load those oxygen generators into an aircraft. As far as he (and all the other mechanics) were concerned, the generators were to be thrown away, not transported. The defence also argued that there were other factors contributing to the fire, including faulty wiring issues. The two employees (the Director of Maintenance and the remaining mechanic) were acquitted of all charges.

SabreTech was aquitted of most of the counts, including conspiracy, but found guilty on nine charges relating to the reckless transportation of hazardous materials and failing to properly train its employees. The case was later appealed and eight of the charges were dismissed; the US circuit court only upheld the the charge of improper training.

This means that if Valenzuela had stayed and gone to trial, he would have been acquitted. However, by then he was already on the American Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) most wanted list as a fugitive.

In 2011, the New York Times questioned whether this was sensible.

Indicted in 1996 ValuJet Crash, Airline Mechanic Still on EPA’s Most-Wanted List

Considering the outcome of the case, there is some question as to what the government would do if they are able to one day capture Valenzuela and bring him back to the United States.

Alicia Valle, a spokeswoman and special counsel to the U.S. Attorney in the Southern District of Florida, declined to comment about what might happen in that scenario.

“Valenzuela already is charged … in one case with the SabreTech matter, in the other case with bond-jump [and] contempt of court,” Valle said. “We really cannot speculate about which charges we would go forward on if the fugitive were arrested.”

Now, 22 years after the tragic crash, the FBI has offered a $10,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of the mechanic and released a new WANTED poster, showing what the man might look like now.

ALERT FBI offers $10,000 reward for arrest in ValuJet 592 crash case

“We’ve tried over the years to find him,” said [FBI Miami Special Agent] Fruge, who has been a special agent for 29 years and hopes to close this case while it’s under her watch. “It bothers me. I’ve lived and breathed it for many, many years.”

There’s no question that the crash of ValuJet flight 592 was a terrible tragedy. The investigation highlighted serious issues at the airline, the maintenance company and the overseeing authority, the FAA. The day after the crash, the FAA administrator announced to the media that ValuJet was a safe airline, assuring the public that he would fly the airline. He asked for trust in the FAA to do their job and it was only a detailed and unflinching investigation by the NTSB that showed that the airline was not safe and that inspectors at the FAA had been worried about ValuJet for quite some time for cutting corners and repeated issues.

Thirty-three safety recommendations were made and many regulations were put into effect which increase the safety of airline passengers and crew to this day. More importantly, it forced the US and the world to focus on safety in the aviation industry the importance of proper government oversight.

However, this latest update does nothing whatsoever to improve aviation safety. The families of the victims of that awful crash are said to want closure, but they already know that the identical case against the other mechanic was dismissed, as was the case against the Director of Maintenance, as were 23 of the 24 charges against SabreJet. Whether they believe that the result was correct or unfair, chasing down this last mechanic is not going to change that outcome. He’s already lost everything for something that he likely never even understood.

I was initially intrigued to see a current investigation relating to ValuJet 592 in the press so many years after the crash but, when I realised what it was about, I just felt sad and tired.

The full report is available on the NTSB website as a PDF. You can also read the 33 recommendations that were made as a result. I also recommend this article from The Atlantic which I quoted above: The Lessons of ValuJet 592.

Strictly speaking, the oxygen generator does not “contain” oxygen. It contains an oxidizing chemical, such as sodium chlorate. Burning the oxidizer produces oxygen, along with a great deal of heat. So the SabreTech description of the oxygen generators was doubly inaccurate.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemical_oxygen_generator

Thanks for this; I wondered about that but I wasn’t sure quite what was happening there.

Another interesting article. I remember learning about the accident as I was in the Orlando airport waiting to get on one of ValuJet’s competitors.

I notice you say he is on the EPA’s most wanted list, however the wanted flyer is from the FBI, which is much more likely.

He was on EPA’s fugitive list for ‘environmental crimes’. However, the website (which in 2011 was epa.gov/fugitives) no longer exists. The FBI makes a lot more sense but I think that’s because the key issue now is his jumping bail rather than the actual issues of the crash.

When I was still active and flying (well, I am still active, just nor flying any more) our aircraft were equipped with oxygen generators. They were part of an elaborate mask, not all that dissimilar to gas masks.

We were flying cargo, it was on board to deal with problems like fire, spillage and other situations involving dangerous goods..

We were trained how to use them but not really how it worked.

The oxygen, apparently, is bound chemically until released by a process that also can generate a lot of heat unless the release of the oxygen is controlled. Which, apparently, takes place in the mask. Or something like that. We were not really told that the masks themselves could be a hazard, the training we received was mainly about handling and storage of hazardous good, how to deal with unusual situations, how to find and identify them in the cockpit using the handbook, how they must be stored, how much can be packed together, limitations when carrying hazardous goods on board passenger-carrying flights and how to identify the hazardous goods and the proper storage using the manuals and the “NOTOC”.

So even when handled professionally and loaded by professionals, which fortunately was the case in the cargo aircraft I used to fly, the crew does not always know the finer details. In our case, only the basics were covered on a “need to know” basis. So it does not need a lot of detective work or psychological skills to imagine how people not to used to nor trained to handle dangerous goods can make this kind of mistake. With lethal consequences.

But, what emerges is a series, a sequence of small but very significant events, all caused by casual attitudes and complacency by virtually all involved, except perhaps the flight crew.

PS: did the DC9 have cables to the controls?

The BAC 1-11 had rods that operated hydraulic actuators. In the event of a hydraulic failure “manual reversion” would couple the rods, bypassing the hydraulic system. Controlling the aircraft in “manual” was hard work, but it was possible. I suppose there must have been cables to the rods, working from the actual cockpit controls. That part I have forgotten. But if any fire would have reached the cockpit and burned that part through, hopefully for them the pilots would have been dead already.

What a terrible tragedy !

What good is finding the guy? By the time these disgusting lawyers finish he’ll be getting a $1M settlement in his favor for harassment.

I have to say the Board did a really good job.

I remember this case very well. I was scheduled to fly on VJ a couple of weeks later; the flight was canceled, and I considered myself lucky to have gotten other transport on a holiday weekend without having to fork over a wad of cash. I hadn’t realized before then that the “oxygen” was actually a dissociating compound (similar to what high-school chemistry labs had students use to generate small amounts of oxygen for experiments), but it made sense — it probably gets more oxygen in less space and less mass (because the containers don’t have to take 100-200 atmospheres of pressure). I suppose there’s less worry about fire when the cabin is decompressed, but I wonder about that much heat that close to people’s faces. (The link above notes that the generators may be in seat backs in jumbo jets because the ceiling is too far away.)

From what I read at the time, this was another case of the fish rotting from the head; it’s a pity that Sabre-Tech management wasn’t indicted and convicted right up to the top for driving employees to take on too much work. The FBI move is utterly appalling; I wonder who they think they’re kidding? This seems too small-scale to be related to the current political mess, but somebody might have thought they had to prove they were focusing on “real crime”.

Rudy — interesting to hear you were given a generator; the link \says/ pilots usually get bottled oxygen instead, but there’s no room for discussion of how general that is or how long it’s been true.

When I was flying DC-9s and MD80s the pilots had an oxygen bottle mounted behind the copilot that fed the cockpit oxygen masks. Aviation oxygen is specially treated to reduce moisture, I don’t know if any such treatment is used on oxygen generators.

Chip,

The oxygen generators were on board of cargo aircraft I used to fly. The interiors had been stripped, even the galley had been removed.

We had oxygen generators, not issued to individual crew members but as part of equipment to deal with situations resulting from the transport of hazardous material. These oxygen generators covered the entire face, not unlike a gas mask and likewise had goggles.

This was intended to make it possible for a crew member to deal with a situation e.g. where toxic material gave off vapour or gas. It was not necessarily to fight fires but to prevent the crew from being overcome a situation where breathing would become impeded whilst being out of the cockpit to investigate a problem with chemicals in the cargo area.

Ross,

Interesting bit about the DC9.

The BAC 1-11 did not have a passenger oxygen system. It did have a bottle for the cockpit crew and portable bottles for the cabin. They were there for the cabin crew and for passengers with a medical condition that would require oxygen, not necessarily because of a decompression. Which was not really a problem associated with that type of aircraft as they were built to a very high standard. Structurally, they could still be flying. There had been plans to replace the noisy and thirsty Spey engines with the later Tay.

This gave aircraft manufactures the shivers. There was no real interest from the side of the industry to re-build BAC 1-11 with more modern and more efficient engines. This would have required a complete re-certification process. In the end this was considered to have been too costly.

And yes, I do believe that oxygen used in (passenger jet) aircraft has been dehumidified. This to prevent ice forming.

Two issues at play:

– The air is very cold at altitudes. A crew making an emergency descent must not suffer from oxygen deprivation.

– Expanding gas will cool. Rapidly expanding gas may cool down to sub-zero temperatures even in normal ambient air. So the same philosophy applies: if and when a crew needs oxygen, the last thing they need is oxygen starvation caused by freezing of valves or regulator due to moisture in the bottle.

Also, air pressure is not important, on the contrary, any pressurized gas without or with malfunctioning regulator valves would have a devastating effect on the passenger’s lungs when the cabin is depressurizing.

The only important part is to get the partial pressure of oxygen to be around the 210mbar as it is on the ground. If the surrounding atmosphere is little over that value, breathing pure oxygen is what helps best, pressurized air wouldn’t help.

As bottled oxygen doesn’t heat up as a generator does, I’d guess crews are expected to use bottled oxygen to be able to pick it up and walk around, unlike passengers who are supposed to stay in their seats in an emergency.

When operated at normal room temperature, the outside of the oxygen generators can reach up to 547°F (286°C).

Compare to the infamous Farenheit 451; that is, this is clearly hot enough to ignite flammables on contact.

More generally, this highlights the same lesson a certain famous director learned a little while ago: If you get arrested and tried, eventually the trial will be over, and if there’s a sentence that will finish in time as well. If the mechanic hadn’t fled, he’d probably have been acquitted with the others; if he had been convicted, his sentence would probably have been over by now.

But if you jump bail (or, like the director, flee between conviction and sentencing)… then it’s not over until they catch you or you die.

And the oxygen generators on the ValuJet flight were wrapped in bubble wrap. As I recall, the NTSB’s tests revealed that the heat from the oxygen generators melted the bubble wrap and the liquified plastic ignited, which then ignited the other flammables around it. Without the melted plastic, the cardboard boxes might not have caught fire.

I was sent to “Air Load Planner” school while in the US Army. I had been a helicopter mechanic before but was now a WO-1 Pilot. All the rules of the USAF and DOT about cargo handling made most whine and complain. But it was obvious to me that this incident was a real teaching point to use with Army ‘mission first mission always safety sucks press your luck’ types who dominate the US Army. When I told our LTC Squadron Commander I couldn’t certify his vehicle for transport via air due to a fire extinguisher that had to be secured or stored properly, I explained the ValueJet crash and how the whole aircraft was lost due to failure to comply with the regs. I explained if the extinguisher was left rolling around the vehicle, and the aircraft had to make a violent maneuver, the top of the extinguisher could break and create a projectile that, heaven forbid, hit something important, bye bye plane. He listened, and I said all you have to do is get a strong box and take the handle off the extinguisher and pack it using a blanket or whatever and close it up. Then the light went on, it was so simple, so easy why not. His driver who had complained about this request was quickly dispatched to do just that. There are real reasons for the regs, follow them.

Here’s an interesting link, apparently written by a Douglas employee back in 2003, he believed a relay in the forward cargo hold started the fire, not the oxygen canisters…

http://www.iasa.com.au/folders/Safety_Issues/FAA_Inaction/moreonValujet592.html

Interesting. Thanks for that!

Last I recall, and I was a contract structure mechanic working at Sabretech in Miami at the time of the crash, the guy was working at Dalfort a year or so afterwards. He drove a nice looking Corvette Stingray, still going as Maury Valenzuela, and had long curly hair to his shoulders.

Our understanding was that “ALL” involved we’re cleared though.