Navigating Instrument Failure at 10,000 Feet

I’m not here! I’m celebrating Thanksgiving in the US for the first time in 30 years, so I do hope someone has organised a double-batch of cranberry sauce.

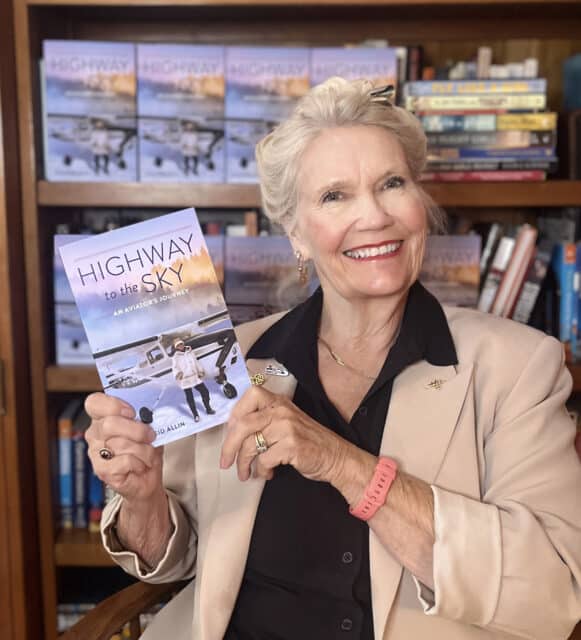

Don’t worry though, I have a great guest post from my friend Lola Reid Allin. Lola was among the first female commercial pilots, breaking barriers in aviation when airliners were almost exclusively male territory.

Lola went on to become a commercial airline transport pilot, flight instructor, SCUBA divemaster, and an award-winning author and photographer.

To put this in perspective, when Lola was fighting to earn her ATP certificate – the highest rating possible – only 2.3% of all pilots in the US were female. Even today, females make up less than 6% of commercial pilots worldwide. Lola’s memoir, Highway to the Sky: An Aviator’s Journey (just released!) offers a candid look at her experiences in this challenging field.

I hope you enjoy her account of navigating instrument failure in severe weather conditions – a situation that would test any pilot’s skills and nerve.

How I conquered malfunctioning instruments in bad weather…on a scheduled flight that should’ve never taken off!

By Lola Reid Allin, author of Highway to the Sky: An Aviator’s Journey

Termination of a flight exemplifies expertise, not cowardice.

During my drive to the company hangar at the airport, I become increasingly convinced the captain will cancel our scheduled flight.

But aircrew are required to show up an hour before departure, so here I am, shrouded in my car, visibility reduced by distorted smears of grey to less than ten feet beyond the headlights, battling the elements for a fifteen-minute struggle instead of the usual five-minute commute. Wipers whiz past my eyes and raindrops sound like a thousand golf balls bashing metal. Water sluices in gullies along the sidewalks, dead leaves spiral into the air and discarded plastic bags transform into tumbleweeds.

After getting a thorough weather briefing and hard-copy printouts of current and forecast weather for departure, enroute, and destination airports, I head to our pilot lounge, where Captain Gavin examines the load manifest.

I pony-tail my long hair, disheveled by the tempest brewing across much of central Canada, and say, “We’re in for a treat today. Surface winds are already thirty knots gusting to forty-five. Gale-force upper winds sixty to ninety. Forecast much stronger, up to one hundred knots.”

A smirk spreads across his face. “Little wind got the little girl scared?”

I ignore his insult and say confidently, “The storm spans three provinces. We can expect extreme thunderstorms, turbulence, torrential rain, and fog. And we might have trouble finding a legal alternate airport if our destination craps out.”

He ignores me.

“Some of the pilots at the weather office decided to delay or cancel their flights.”

Sarcasm spills across his tight lips. “Do yeeeoooouuuu think we should cancel?”

With horror, I understand he plans to proceed. Although I don’t expect him to agree with me, a junior first officer, I must emphasize my opinion. “Yes.”

“All the passengers have checked in, plus there’s important freight.”

“I’ll bet they’d rather arrive alive tomorrow than dead today!”

He stands and strides toward me until his nose is six inches from mine. “We’re going.”

His disregard for personal safety–his, mine, and the passengers—puzzled me.

Our company doesn’t pressure pilots to take foolish risks, and my no-go decision might have had the support of the chief pilot and the sympathies of my peers, but more likely another first officer would jump at the chance to replace me.

Or maybe he’s right. After all, he’s a senior captain with this company, with a decade of experience flying in the wilds of northern Canada, and not known to make foolish decisions.

I wanted to bail but figure (hope) the weather will hold, at least to our first stop.

Be self-reliant: use your knowledge and experience.

Gavin flies the first leg and I’m the pilot monitoring (PM), a nonflying, auxiliary role. I’ll fly the next leg —that is, if we’re still flying. My rotation as pilot monitoring will mean scrambling for updated weather, requesting altitude or route changes, or radar vectors around weather.

Because we’re instrument-rated pilots, flying IFR and navigating with instruments only, we aren’t required to use any maps other than those designed for instrument flight. However, when I don’t have hands-on control of the aircraft, I keep myself occupied by using topographical maps to determine my precise location.

Today, identifying ground features will be a major challenge, not a casual pastime.

Turbulence tosses us up, down, and sideways. Blood pumps against my temples with the steady thump of a bass guitar. I tighten my five-point harness that secures our shoulders and hips, with a belt between our legs to prevent us from slipping forward. Out of the corner of my eye, I see Gavin tighten his harness.

One hour out, our ground speed is an absurdly slow: seventy knots as indicated by our distance measuring equipment (DME). Both engines produce the correct power for our standard cruising speed of one hundred and forty knots, but the wind must have shifted to head-on.

I mention this to Gavin. He shrugs. “Yeah, I saw it. Probably wrong.”

“Superstrong headwinds were predicted.”

This time, he doesn’t bother to respond.

I say, “For fun, I’ll use instruments to triangulate our position.”

He drawls, “Don’t bother. We’ll get there eventually.”

Understand that complacency kills.

I ignore him, select three VOR stations, determine our radial from each of them, draw it on the map, and determine our approximate position based on the intersection of the lines. Then, like the pioneer aviators, I bring out my manual flight computer, a circular slide rule invented in the 1930s, to plot distance flown against time in the air.

Gavin sniggers. “Why bother with that old-fashioned crap?”

I ignore him. “My calculations agree with the DME readout of seventy knots.”

He grunts and settles deeper into his seat. Cars on two-lane highways are moving faster, but he doesn’t seem concerned. Lured by the siren song of familiarity, inside a dependable aircraft with reliable instruments, I can only guess overconfidence has spirited him to la-la land.

Radio chatter increases as pilots request updated weather for their destination or vectors around embedded thunderstorms popping up on radar. Others turn around—but Gavin drives us westward, deeper into the vortex of silver clouds bubbling toward the stratosphere.

My shoulders tingle when a Boeing 737 pilot requests revised routing to avoid the weather. If a one-hundred-and-thirteen-thousand-pound Boeing 737 diverts to avoid weather—What fate will befall our twenty-passenger, twelve-thousand-pound turboprop?

I should’ve refused this flight, even if that meant canceling the flight and inconveniencing passengers. Calmly but with a deliberate sense of urgency, I say, “Let’s turn back.”

All I get is a scathing, sidelong glance as if I were a buzzing fly that won’t stop pestering him.

My luck to fly with a captain deluded by “get-home-itis” a potentially deadly affliction that causes pilots to equate termination or cancellation of a flight with defeat and to push the limits of the airplane, the weather, and their personal capabilities. Each successful push beyond the limits, each evasion of the grim reaper, escalates the temptation to push further the next time.

Abruptly, the LED numbers on one of our three navigation-communication radios change to a dashed line. The radio has power—but isn’t picking up a signal.

I select several different stations and wiggle the dials, but I can’t pull in any stations.

Gavin says, “Guess that radio went tits up.”

This is a hassle but not a catastrophe because our other two navigation-communication radios continue to function normally. I’m not worried until a minute or so later, when the remaining two radios keel over.

Be aware that fear is normal.

Now, bundled inside clouds without sight of the ground and without navigational equipment, we can’t confirm our position or plot a course to our destination.

Without communication radios, we can’t contact a controller for radar-assisted routing direction, get weather updates, or contact our station agent.

My chest constricts as if swathed in a straitjacket. If we don’t crash, I’d like to report his bad decisions to the chief pilot, but my word will be the word of a junior first officer against a senior captain. Will making a big stink get me fired or resolve my concerns?

Invisible hands strangle my throat. I force a deep breath of air, then synchronize my breathing with the steady throb of the engines. Be calm. I fiddle with the radios, change frequencies, attempting to contact anyone who might hear us. Nothing works, so I say, “Maybe the electrical storm disrupted signals from the ground stations.”

He says, “We still have our basic flight instruments. And strangely, the DME.”

“That’s a plus.”

But we both know that flight in cloud using basic flight instruments plus one navigation radio, the DME, is difficult and dangerous, not to mention illegal when carrying passengers.

Gavin says, “Based on our elapsed time, we should be directly overhead.”

“We shou—”

“D’ya see anything?”

“Gavin, ‘should‘ is the key word.” With horror, I realize he hasn’t considered the implications of our reduced ground speed. “You’ve flown these routes hundreds of times more than me, but . . . we haven’t covered the amount of ground we normally cover.”

He’s the captain, so I wait for him to suggest a plan. I’m hesitant to interrupt his thought processes—but remember reading about crashes that might’ve been averted if the junior pilot had spoken up. I say, “I don’t want to argue but our slow ground speed means we’re farther east than usual. Can you see anything?”

Panic is dangerous –learn to recognize the signs.

He seems hypnotized by the instrument panel. I might as well chat with the altimeter. I don’t expect small talk, but we need to communicate. Forward visibility is impossible, so I squash my face against my side window and peer straight down, hoping to identify anything.

He says, “I see trees!”

“If we were on track, we’d see water.”

He says, “So, smarty-pants, where are we?”

“I’m . . . not exactly sure. What should we do?”

I hope his continued silence means he’s considering a solution and not detached from the reality of our predicament. With each passing second, as he impersonates a zombie instead of a captain, my dread quadruples. I have no idea how to get out of this mess, and apparently, he doesn’t either.

We continue—because we have no other choice.

Why’s this arrogant smart aleck suddenly spineless?* My frustration increases exponentially. I’m annoyed he insisted on this flight —and furious with myself for not refusing the flight.

Know when to be assertive.

I approximate our current position and determine a rough heading to our destination. One of us needs to make a decision. I say, “I guesstimate we’re forty miles southeast of our destination. Steer heading three-two-zero.”

To my relief, he complies. Time stops as we drift in an ocean of burbling clouds, floundering without an island of safety in sight. What if the cloud layers thicken and obscure the airport? I push this out of my mind because I know the result—we’ll sail above the airport and miss our only chance to land before we run out of fuel.

My heart jackhammers against my ribs.

Suddenly, unbelievably, the cloud layers shift to reveal a skinny splinter of land. I pump my arm like an excited schoolgirl desperate to answer a tough question and point at the rotating beacon of an airport near our destination.

We’re in the right place, at the precise moment, to reestablish our bearings. We’re ten agonizing minutes to safety, but the approaching twilight in the relentless rain makes visual flight increasingly difficult. I scan the instruments, hoping one might spin to life.

What if something else goes wrong?

Minutes later, cotton-batten clouds engulf our plane. My pulse races as I check the map to confirm we’re not going to mash into life-terminating towers. Gavin descends cautiously through a layered hell of cloud levels. Fractured glimpses of ground taunt us until a good fairy creates a cloud valley leading to the airport.

One-half mile from the runway a diabolic meteorological treachery reduces our cloud crevasse to a narrow V. A surge of bile stings my throat. Sheeting rain streaks the windscreen, but I don’t dare lose sight of the runway. The tires squeak onto the runway seconds before the cloud drops to the grass, burying us under a coverlet of steel-gray fog.

Flickering lights on our instrument panels catch my attention. Now, safely on the ground, the red LED lights on our radios spring to life and dance.

The devil has released his choke hold grasp on our lives.

I’d like to thank Lola for sharing this gripping account with us.

If you enjoyed her story, feel free to leave a comment — I’m sure she’d appreciate hearing your thoughts! You can find out more about her or pick up a copy of her book at https://www.lolareidallin.com

I’ve read way too many instances of that kind of macho !@#$%^&*()!!-head behavior; my first reaction to the first few lines of dialog was to wonder whether he would have behaved the same way with a male co-pilot; some men are afraid to be seen by a woman as less than all-powerful. (Such fear is cowardice, even if some wouldn’t recognize it.) I’m just glad she survived to write up the story.

I was hoping to hear if there were any repercussion, and if Lola Allin continued flying with that colleague or not.

Lola writes:

Yes unfortunately, partly due to my concern about “making waves” and drawing more attention to myself, but also because I knew I was leaving Northern Ontario in a few months to finish my undergrad degree.

I’d finished 3 years of a 4-year Honours BA via correspondence, but in the days before the internet, I needed to be on-campus to complete the senior honors seminars requirements and the stats courses.

It was a mistake because he was constantly surveying me waiting for an error and quick to report anything that might be construed as detrimental. His real name is not Gavin, but I renamed him because he watched me like a hawk (Gavin, meaning hawk or falcon). And it was a mistake because others could have learned from our experience.

Unfortunate, but understandable. Thank you!

The number of time people get away with these things, just one hole in the Swiss cheese doesn’t line up…

Even with my little piloting experience, I had a close call on my first solo. The things we get away with…